I’ve always been fascinated with William Ford, ever since I first saw his name in the records. For a start, he was a mathematical instrument maker, an occupation I’d never come across before. It’s amazing to think that he made all these sophisticated, state of the art, precision instruments in his own workshop. He must have had a thorough knowledge of mathematics and scientific principles. Wapping, this vibrant place of maritime activity full of colourful characters, where William Ford lived, also sticks in your imagination. You can picture the sea captains, with their tales of adventures in far-flung lands, visiting his shop. A particularly pivotal year in William Ford’s life was 1861, so it’s here that I’ll start his story.

It is 1861 and William Ford, a skilled mathematical instrument maker, has his own workshop in his father’s former home at 21 Lower Gun Alley, Wapping, close to the River Thames, the flowing life blood of London. Like his elder brother, John, who was a mathematical instrument maker in nearby Shadwell, he had followed in his father’s footsteps. It was his father, John Ford, who had taught him the skills to make marvels of beauty and science out of brass and glass. The convenient location of William’s shop, close to the River, meant that it was easy for sea captains to come ashore to purchase a compass, a sextant, or maybe a telescope: any instrument that they might need for their voyages navigating the world. His father had died a few years previously, and William had received a generous legacy from his father, inheriting property in Poplar that he would receive after the death of his mother. It would seem that William was in a good position, making a decent living from running his own business and with the prospect of a sizeable inheritance to come.

Wapping was a thriving maritime community, full of ships’ chandlers, sailors, lightermen, riggers, and trades connected with the sea, bordered by the River Thames, the highway of London. Tea cutters, schooners, wherries and ferries, barges and lighters, ships from all over the world, passed by or docked to unload their precious cargoes in Wapping’s massive warehouses. It was the centre of nautical commerce and trade.

Oil on canvas, painted at The Angel tavern, Rotherhithe

Whistler lived in Wapping for a few years from 1859

Image courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Of an evening, you could smell the scent of tea and spices in the air that were stored in one of the great warehouses at Tobacco Dock, mingled with other less than savoury smells. You might hear tinkling from ships’ rigging on the river, the muffled sounds of laughter from one of the many taverns on the riverside, drunken sailors cursing as they made their way back to their lodgings.

Wapping had its dark side. Though some of the sea captains lived in large houses in the area, Wapping was full of dirty alleys, squalid courts and grimy yards where the poor lived in crowded, unsanitary conditions. An 1848 survey of 1651 heads of families found that most existed on less than 25 shillings a week with only 17% earning over 30 shillings. Boarding houses, notorious taverns and seedy saloons brought crime and unsavoury characters to the area. Drunken fights, suicides and bodies found floating in the river were not uncommon occurrences. Brothels and dingy opium dens abounded. Dickens himself visited an opium den in the area in 1869, under police escort, when researching his latest (and last) novel, Edwin Drood.

Wapping was also the site of Execution Dock where pirates would be hanged from a gibbet with a shortened rope, (ensuring a long and painful death), after being escorted from the Marshalsea Prison at London Bridge. Onlookers would gaze in fascinated horror at the grisly sight of bodies on the gibbet. It was positioned low to the water but away from the bank and bodies were submerged three times by the tide before they were taken down. The most notorious pirates had the dubious privilege of having their bodies tarred and exhibited in cages along the Thames Estuary after their death. The body of Captain Kidd, who was executed in 1701, and the inspiration for Treasure Island, remained in its cage for 20 years.

William Ford was a native of Wapping. He had been born on September 29th 1819, and was baptised at the parish church of St John, Wapping the following year on October 29th:

London Metropolitan Archives

via http://www.ancestry.co.uk

The rest of the church was destroyed by a bomb during the Blitz

http://www.geograph.org.uk

In 1842, when a young man of 23, William Ford married his sweetheart, Ann Robson at the nearby parish church of St Dunstan’s Stepney, known as “The Church of the High Seas” because of its traditional connections with the sea. Both parties gave their residence as Mile End Road:

London Metropolitan Archives

via http://www.ancestry.co.uk

Both William Ford and his father, John Ford, were described as opticians in the marriage register. One of the main skills of mathematical instrument makers was to grind glass to make optical instruments. It is not surprising that part of their business involved the making and repairing of spectacles, hence they are sometimes recorded as opticians. There was no livery company as such for mathematical instrument makers, (their profession was relatively new), to regulate the profession and provide training. However, many mathematical instrument makers joined other livery companies such as the Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers, Clockmakers or less obvious choices such as the Joiners Company. Perhaps John Ford and his sons belonged to one of these companies.

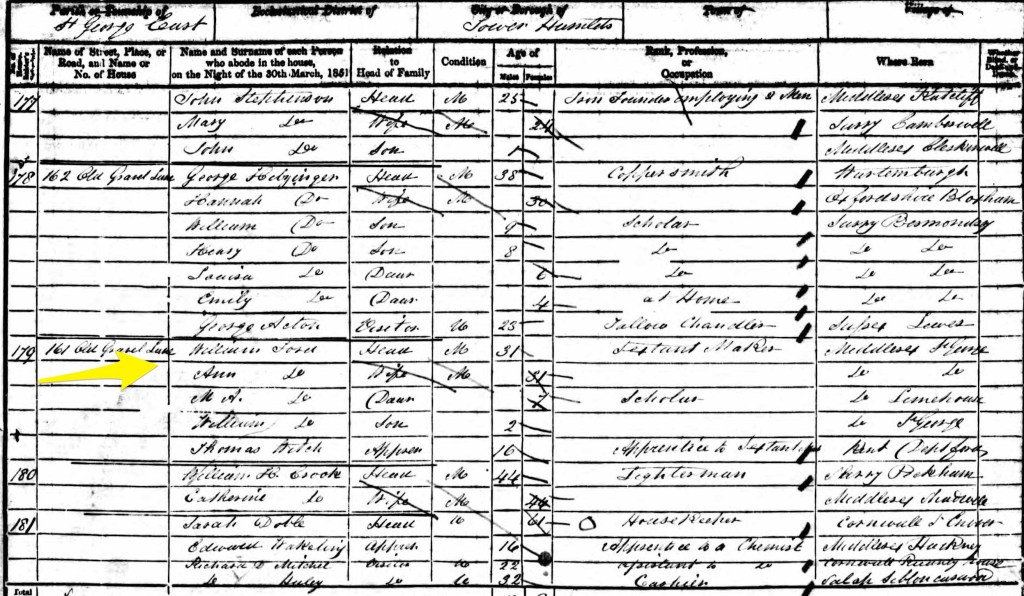

By 1851, William and Ann Ford, were living at 161 Old Gravel Lane, (now Wapping Lane), one of the main commercial thoroughfares in Wapping. Many warehouses had been built on this road as it ran north to south from St George Street and the parish church of St George in the East, to the river at Wapping High Street. William and Ann now have two children, Mary Ann (shown here by her initials), b. 1843 in nearby Limehouse, and William, b. 1848 in the parish. William is described as a sextant maker, and is training one apprentice, Thomas Hitch, who is living with them:

HO 107 1549 134 The National Archives

via http://www.ancestry.co.uk

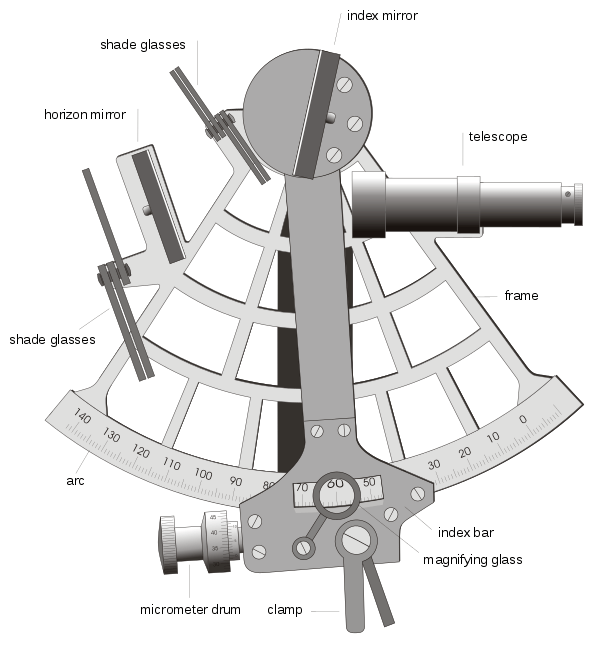

A sextant was an essential aid for a sea captain. A doubly reflecting navigation instrument, it measured the angular distance between two visible objects. At sea, it was used to measure the angle between an astronomical object and the horizon for the purposes of celestial navigation:

Image courtesy of Wikipedia

In 1856, tragedy struck as Ann, William’s wife, died. However, William was not on his own for long for he had a new lady in his life. He found love with Elizabeth Mumford Dixon, nee Hooper, who he married later that year:

Elizabeth was a young widow with one daughter, Kate (b. 1850). Although she was originally from the Scilly Isles, her father, a master mariner, had moved to Liverpool for business. Her first husband, James Dixon, also a master mariner from the Scilly Isles, probably died at sea. William and Elizabeth may have met through William’s brother Robert. Robert was a master mariner, as was Elizabeth’s brother, Clement Hooper, and Robert is a witness at the marriage. (Clement Hooper was a witness at Robert’s own marriage the following year). Mary Ann, William’s daughter and eldest child, also signed the register. She was a mere 12 years old. I wonder how she felt at having a new stepmother?

In November 1857, John Ford senior (described rather vaguely, as a shop owner when his son,William, married the previous year and a tradesman when his son, Robert, married in October that year), passed away at his home at 20 Lower Gun Alley, aged 79. He left an estate worth just under £3000 (ca. £177,000 in 2017). He had been successful enough in business to invest in a ship and property, owning six houses in Lower Gun Alley, Wapping, along with six houses in Regent’s Street, (now Gasalee Street), Poplar, which had been built on the former rope yards of the East India Company. The houses in Poplar were left to his eldest sons, William and John. Their younger brother, Robert, who was a master mariner in Rotherhithe, which was directly opposite to Wapping, on the southern bank of the Thames, received the houses at Nos. 19, 20 and 21 Lower Gun Alley. Their sister, Esther, and her heirs, were given nos. 22,23, and 24 Lower Gun Alley, Esther being in receipt of the rents until her death. However, John Ford stipulated that all his real estate and the rents received were for the use of his wife, Mary, until her death. The children were going to have to wait to receive their inheritances.

The clock tower of St John Wapping can be seen in the background

Watercolour by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd 1850

@Trusteees of the British Museum

In the early 19th century, huge warehouses and docks had been constructed in Wapping, which had destroyed a lot of the housing. Squeezed between the high walls of the docks and the warehouses, Wapping had become rather isolated from the rest of London as it was only accessible through four canal bridges. Ships entered and left the docks when the bridges were raised at high tide so during these times, Wapping was cut off.

Image courtesy of www.stgitehistory.org.uk

Wapping is the area hemmed in by the docks.

The yellow arrow shows the position of Lower Gun Alley

The right arrow the position of Old Gravel Lane

Wapping therefore benefited considerably when the Thames Tunnel was constructed, overseen by the famous engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. The tunnel connected Wapping with Rotherhithe across the river, and it was finally opened to the public in 1843. It was the first tunnel ever built under a navigable river. Construction was begun in 1823 by Marc Kingdom Brunel (Isambard’s father), and Thomas Cochrane, who had invented a new tunnelling shield. The tunnel was originally designed to carry horse-drawn carriages but due to cost, the plans were scaled back so it was only open to pedestrians. It became something of a tourist attraction. Two million people paid a penny every year to pass through. In 1869, it was converted into a railway tunnel and is still in use today. William Ford and his parents must have used the Thames Tunnel frequently, as both Old Gravel Lane and Lower Gun Alley in Wapping, were very close to the Wapping entrance. Likewise, William’s address, when he proved his father’s will in 1858, was Princes Street in Rotherhithe, very near to the Rotherhithe entrance.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia

As we have seen, by 1861, William Ford was living at 20 Lower Gun Alley, his father’s former home:

RG 9 281 145 National Archives UK

via http://www.ancestry.co.uk

The house was shared by John Crawford, a dock labourer and his wife as well as the widow, Sarah Goodchild, a washerwoman and her three adult children. There is no indication that William Ford was employing any workers (his brother, John was recorded as being an employer of six men at this time). Mary Ford, William’s 74 year old widowed mother, was also living with them but is enumerated on the next page. She is described as a “Proprietor of Houses”. Her husband had left her very comfortably off but perhaps, as it was a large house, she could boost her income still further by renting rooms out. William’s daughter, Mary Ann, is not recorded in the home but was living instead with a maternal aunt and uncle, though her younger brother, William, is living with his father, stepmother and young half brothers, John C Ford, b. 1858 and Clement Ford, b. 1860.

An event happened less than two months after the census was taken, which may be the reason why William Ford was not employing any workers at the time. William Ford made the decision to leave Wapping, his wife and young family, and accompany his thirteen year old son, William, to New Zealand. As the eldest son, the expectation would be that William would train as a mathematical instrument maker under his father’s supervision. Perhaps William had other ideas and wanted to see the world. Maybe his father was keen that he should get away from bad influences, closer to home.

Why was New Zealand chosen? In 1854, James Dixon, Elizabeth’s first husband, was the captain of a barque of 380 tons called the Monarch, built in the Scilly Isles. It was chartered to visit New Zealand carrying goods, rather than passengers, and Elizabeth’s brother, Clement Hooper, another Scillonian and master mariner travelled with him. Perhaps William and Elizabeth had heard tales by the fireside of the amazing opportunities that could be found in this new British territory, which was actively seeking immigrants to settle there. Robert, William’s brother, was also a master mariner so perhaps he had visited too and given a good report. What we do know, (from William’s obituary in New Zealand), is that William junior worked his passage as a cabin boy on the Northumberland, a ship of 811 tons, accompanied by his father. It left Gravesend, a little further down the estuary of the River Thames, on May 10 1861, embarking on a voyage that could take around four months, if all went well:

http://www.paperspast.natlib.govt.nz

Given that childhood had ended by the age of 13, it seems unusual that his father would have accompanied William junior. In 1852, the cheapest price for a one way ticket on a ship belonging to Willis Gann and Co, was 15 guineas for steerage for single men. That was equivalent to the price of a horse or 4 months wages for a skilled tradesman. Perhaps William Ford came to some arrangement with the captain. I wonder whether William Ford senior wanted to check out the country and see for himself if it would be a suitable place for a fresh start for his family? It must have been a worrying time for Elizabeth, especially as she was pregnant again. She gave birth to another boy, Ernest Herbert Ford on the 23 October 1861. Would she ever see her husband again?

Find out what happened next to William Ford in Part 2.

© Judith Batchelor 2020

You really bring the area to life. The map showing how Wapping was cut off from the rest of the city was very striking. Wapping must have had a strong independent identity.

The sextant diagram is also helpful. It’s amazing that mariners navigated the globe with such manual tactile instruments. I look forward to hearing what happened next.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much for your comments. It’s amazing how important it is to have a good map, especially for an area like Wapping that has undergone such change. Many of our ancestors must have been so talented to make intricate things by hand that are mass produced today.

LikeLiked by 1 person