In Part 1, we discovered more about William Ford’s life as a mathematical instrument maker in Wapping, London, but in this story, we will be finding out about events in the early 1860s that challenged his comfortable existence. When the 1861 census was taken, he was living in the family home at 20 Lower Gun Alley, Wapping, carrying on his business as usual. However, this scene of domestic stability was soon to be dissolved: only a month later, a big change was afoot. William downed his tools, leaving his business in the charge of his wife, Elizabeth, and on May 10th 1861, sailed down the Thames on a ship called the Northumberland. He was embarking on a journey that was to take him to the other side of the world, to Auckland, New Zealand, accompanied by his 12 year old son, William, who was working his passage as the cabin boy on the ship.

New Zealand had first been settled as a permanent colony, just over 20 years previously, in 1840, when British sovereignty was proclaimed and the towns of Auckland and Wellington were founded. Each year, in late spring, ships left the English coast and following the trade winds, brought both goods for the colony and emigrants to populate it. After crossing the Equator, they turned east to take advantage of the strong westerly winds of the Roaring Forties and round the Cape of Good Hope. On the return leg, carrying merchandise such as wool, wheat, or sperm oil, from the whales hunted off New Zealand’s coast, they would head west, taking the dangerous Furious Fifties to get round Cape Horn, the tip of South America before heading north, homeward bound for England. This route was known as the clipper route because many of the ships were of this type, merchant sailing ships, built for speed, that promised fast delivery.

Image courtesy of http://www.wikipedia.org

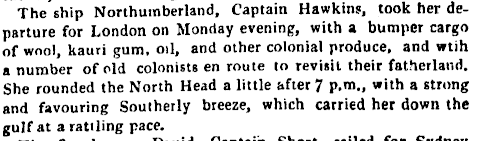

The Northumberland, a ship of 811 tons under the care of Captain Hawkins, arrived in Auckland after a long voyage of 126 days, on 13 September 1861:

New Zealand Newspapers Past and Present

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers

From the above account of the voyage, which appeared in the newspaper, The Southern Cross, the Northumberland experienced some “hairy” moments, with the rudder being damaged in gales after passing the Cape. What a relief it must have been for the passengers and crew to finally reach the harbour at Auckland. Though no official passenger list has been found for the Northumberland, an apparent complete list of its passengers was reported in the newspaper. However, there is no mention of William Ford or his son. It is perhaps not surprising that the cabin boy would not be mentioned, as he was acting as a member of the crew, but what about his father? Was William Ford hired by Captain Hawkins, perhaps for his engineering expertise, given his occupation, and therefore omitted from the list of passengers? In order to get his son the position of cabin boy, William Ford may well have known Captain Hawkins personally. Perhaps Captain Hawkins was one of his long-standing customers.

The first task for William Ford was to get his son settled. In this he was successful, as he managed to get his son a job with the New Zealand Herald, a brand new publication that had just launched. William Ford junior, in the obituary that was published upon his death in 1931, was described as the newspaper’s first apprentice, so he must have received a reasonable education back home in Wapping, and been both numerate and literate. William Ford senior’s brother, John Ford, was already in the country with his family, having arrived in 1859. If John Ford was in Auckland, William would have had someone to stay with and from him, learn more about life in the colony.

After a few months of getting acquainted with the country, it was time for William Ford to say goodbye to his son and return home. It is most likely that he travelled on the return leg of the Northumberland and in the months prior to its passage, the following newspaper adverts appeared:

The Northumberland was described as a fine “A1 teak-built ship”, a classification given to new ships for 12 years by the surveyors, Lloyds of London. This wooden ship was therefore fit for long voyages and carrying goods and passengers of quality. According to the advertisements that appeared in newspapers after its arrival, its cargo consisted mainly of iron, both tools, manufactured products and raw materials, also clothing, carpeting and matting. This was auctioned off, with the importer receiving a mark up in the region of 35% compared to English prices.

The Northumberland sailed out of the harbour at Auckland on 17 January 1862, returning to England with a full cargo in its hold and some “old colonists” as passengers:

New Zealand Newspapers Past and Present

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers

Interestingly, kauri gum, one of the main goods carried by the Northumberland, was a fossilised resin, taken from kauri trees that once forested much of the North Island of New Zealand. During this period, it was much in demand. It was mixed with linseed oil and used extensively to make oil-based varnishes.

After enduring several months at sea, William Ford would have arrived back home in Wapping by May 1862, presumably to a rapturous welcome by his family. They must have been fearful for his safety, wondering if they would ever see him again. A moment of joy for him must have been the sight of his youngest child, Ernest Herbert, who had been born whilst he was away in October 1861. Sitting round the fireside of their home, he would have given an enthusiastic account of New Zealand to his wife, Elizabeth, and the opportunities it offered them for a new life. However, they would have to wait until the following year to make the voyage, as this could only be undertaken from England in the early summer, when the weather was fair.

In the spring of 1863, preparations were being made for the family’s forthcoming voyage. William would have needed to sell off as much of his stock of mathematical instruments as possible before closing his shop. In addition, William and Elizabeth were thinking of getting their three small boys baptised at this time. Though William himself had been baptised in the parish church of St George in the East in 1820, his children from his first marriage, Mary Ann, born in 1843 and William junior, born in 1848, had not been baptised. None of the children from his second marriage to Elizabeth had been baptised either though Elizabeth may have had nonconformist sympathies, as she had been baptised as a Methodist. Perhaps one of the main reasons to get the children baptised was the prospect of the forthcoming long journey and months at sea, with all of its associated perils. Children were particularly vulnerable and one in five children who made the voyage did not survive.

Clement Archibald Ford was the middle son, born in 1860 in Liverpool, where his mother’s family, the Hoopers, were living at the time. He was the first child to be baptised, on Sunday 1 March 1863, but not in Wapping or St George in the East, where the family had their home, but instead, in Hendon in north-west London:

London Metropolitan Archives, DRO/029/005

via http://www.ancestry.com. Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1917

What was William Ford doing in Hendon, on the other side of London? The register states that he was an optician at St Stephen’s House. I had to find out more.

In 1856, the Reverend Charles Fuge Lowder, a founding member of the Anglo-Catholic Society of the Holy Cross, accepted the invitation of the Rector of St George in the East, to lead a mission dedicated to the service of the poor around St Peter’s Docks, Wapping. The society had been founded a year earlier with the aim of banding priests together for a common life of prayer and service to the poor. It also included women as part of an Anglican order of nuns called the Community of the Holy Cross. This was the first Anglican mission to the poor in London and Lowder and his fellow clergy, started their work in Lower Well Alley, just a few minutes walk from Lower Gun Alley where the Ford family had their home. Lowder then opened a small children’s home at their Mission House in Wapping on nearby Calvert Street.

The presence of the sisters, alongside assistant clergy and lay workers, enabled the mission to provide a wide range of activities and facilities, alongside a very full programme of services. These included schools, night classes, clubs, cheap canteens, and a ‘penitentiary’ or refuge for prostitutes. An industrial school, which provided practical training for poor children, was among the early works of the mission. However, it was soon realised that it was necessary to remove the children away from the temptation of the streets so in 1860, former almshouses at Hendon were repurposed and used as premises for the school. The buildings were situated on a high and healthy spot three miles beyond Hampstead and the work was carried on under the name of “St Stephen’s Home”. Similarly, the ‘penitentiary’ for the girls also moved to Hendon in 1860, away from the former haunts of the girls. Since William Ford is described as an optician at St Stephen’s Home, it would seem that William Ford was involved in this charitable work in some way. Given his scientific and mathematical education, perhaps he was providing training for the young boys, so they could acquire skills that would enable them to find good employment. It certainly looks as if William Ford had been recruited by the Reverend Lowder.

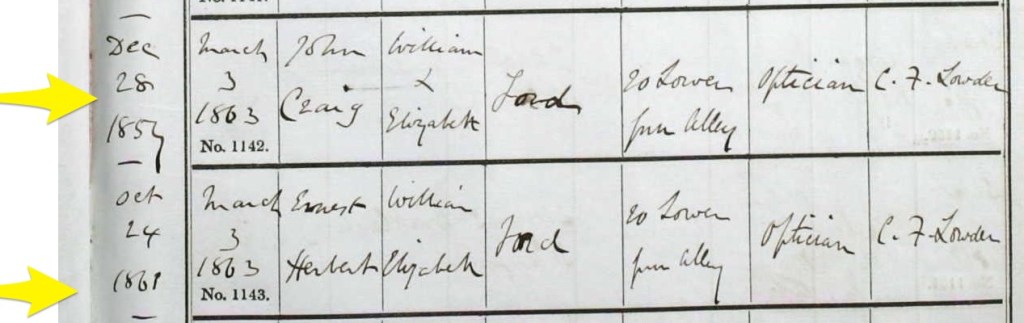

Why William and Elizabeth decided to have Clement Archibald baptised at Hendon (but not the other children), is unclear, as just two days later, on 3 March 1863, their eldest son, John Craig (b.1858) and their youngest son, Ernest Herbert, were baptised close to home. In fact, their baptisms appear both in the registers of the parish church of St George in the East and in a non-printed register for the new mission church of St Peter, London Dock, which at this time was renting the old Danish Church on Wellclose Square, Wapping:

London Metropolitan Archives, P93/GEO/025

via http://www.ancestry.com. Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1917

The ceremony was conducted by none other than the Reverend C.F. Lowder. It is probable that the baptisms took place in the church on Wellclose Square but as it was still a mission church, the baptisms were also entered in the registers of the mother church of St George in the East. A new church was consecrated for St Peter, London Dock in 1866 on Old Gravel Lane, (still in use today), where William Ford had his home in 1851. Lowder was the first vicar.

Lowder was a controversial figure because as an Anglo-Catholic, his high-church practices, rituals and “Romanism” was opposed by many. Riots took place outside the mission, stones were thrown and services were interrupted. However, he was dearly loved by the poor and his parishioners. He is particularly remembered for the sacrificial work carried out by him, and his fellow clergy and sisters, in the cholera epidemic that broke out in 1866, the day after St Peter’s was consecrated.

Finally, the time had come to make the journey to New Zealand. On Thursday May 7 1863, the Captain Cook, left the docks in London and set sail for New Zealand. Elizabeth Ford, her daughter, Katie, and her three young sons are recorded as assisted emigrants in the ledger kept for the Captain Cook but was her husband with her?

New Zealand, Archives New Zealand, Passenger Lists, 1839-1973

via.www.familysearch.org

At this time, the Canterbury Provincial Government in New Zealand provided an assisted emigration scheme to attract people to come to the country. Depending on means, emigrants paid a certain proportion towards their passage. In this case, the cost for Elizabeth Ford, aged 38 and from Scilly, along with her children, was £33, 5 shillings. Elizabeth paid £22 towards this, the net cost to the government being the difference, £12. The absence of William Ford from this record leads me to the logical conclusion that he was not an assisted emigrant, even if his family came under the scheme. It is a bit of a mystery as to why his family qualified but he did not, seeing that all the other families travelled together. William was 43 years old at the time and the upper age limit for the scheme was 40, but of course, he had no birth certificate and who would have checked?

The passengers on the Captain Cook, under the helm of Captain H.C. Cleaver, bid adieu to their native homeland, as it gradually receded from their sight, full of nervous excitement. Many would have to contend with severe sea-sickness in the forthcoming weeks but delights would have included watching dolphins following the ship, marvelling at the fearsome Portuguese man of war, gazing at the magnificent Aurora Australis in the clear moonlit skies, and seeing all manner of sea birds. The long hours would be whiled away playing games, putting on plays and other entertainment and chatting to fellow passengers, on the deck where possible, away from their damp, smelly and crowded quarters below. They would be hoping for a speedy voyage, not least because of the risk of running low on food, water and medical supplies.

I have found no surviving image of the Captain Cook, but she could well have been a fast clipper ship, such as the Newcastle below:

By Thomas Goldsworthy Dutton; William Foster; Day and Son – [http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/149270 Royal Museums Greenwich, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68964830

Unfortunately, for the passengers on the Captain Cook, it was to be nightmarish voyage, stalked by death with sickness on board, and encounters with hurricanes and icebergs. With disease on board ship, it must have been a terrifying time for Elizabeth Ford, fearful for her children and for herself, not least because she was heavily pregnant when she boarded the Captain Cook. On May 21 1863, two weeks into the voyage, she gave birth in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

Despite having a solid profession to fall back upon and a portfolio of houses to inherit, did William Ford have what the Germans call “wanderlust”? Was it an insatiable thirst for adventure that caused him to leave home and take a perilous voyage to New Zealand, not once, but twice? Or was his motivation more to do with a strong desire to create a better life for his children and take them away from the rough, crime-ridden streets of Wapping? There is also his religious beliefs and charitable character to consider. To become a mathematical instrument maker, he must have had education and a good grasp of mathematics and scientific principles. As a man of science, had he followed the theories of Charles Darwin closely and eschewed traditional religious practice by not having his children baptised? We now know that in the early 1860s, he had become a supporter of the charismatic Anglo-Catholic, Charles Fuge Lowder and his work. Did he change his mind about God and this was the reason why he got his sons baptised? Certainly, he was not unmoved by the poverty and the plight of the children in the streets surrounding his home and wanted to do something positive to help them. It is these glimpses of his character that give William Ford a magnetism that draws me to him even today.

Next time, in Part 3, we will learn more about the voyage of the Captain Cook, the baby that was born, and the new life the family made in New Zealand.

© Judith Batchelor 2020

This is a fascinating account. Was William assumed into the crew? His mathematical skills would have been invaluable for navigation. Assisted emigration was also away fo dealing with the increase in the number of people ‘living on the parish’ in the mid nineteenth century and many from rural parishes were sent to a new life down under.

I look forward to the next installment

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for you comment. I am glad you enjoyed the story. I think William Ford could well have been assumed into the crew, at least for the Northumberland. He is definitely elusive in this regard. I may never know for certain but part of the appeal of family history is to look at the evidence and try to think about what really happened. A lot of people did take advantage of assisted emigration. There was an agent from the NZ government in London to attract people to the scheme. A lot of emigrants came to NZ at this time from Lancashire after the American Civil War devastated the cotton industry there.

LikeLike

What a thoroughly well researched and detailed story that raises as many questions as it answers. Why did he make the journey to New Zealand twice? Great article and so well written I’m looking forward to part 3!

LikeLiked by 1 person