In my previous blog, “Margaret“, I told the story of Margaret England, the mother of twin boys, Lewis and William Basing England, who were born illegitimately in Clerkenwell on March 14th 1866. Margaret informed the registrar that the father of her children was a man named William Basing, a footman. This is the story of how I traced him.

Fortunately, the surname Basing is uncommon, so I was not expecting to find many individuals named William Basing in London. In addition, the man I was seeking was a footman, a distinctive occupation. The first step was to search the 1871 census for just such an individual. I soon found my candidate but he was living on the Isle of Wight:

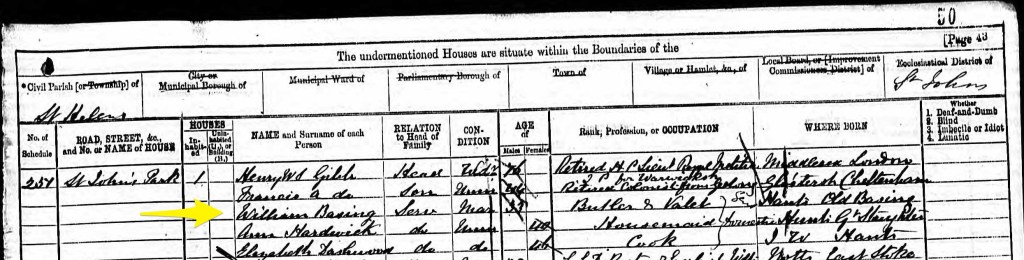

The National Archives (UK) RG 10 1167 50 43 – via www.ancestry.com

William Basing was a butler and valet to Henry W.S. Gibb, a retired Army Lieutenant and a Justice of the Peace (JP) for Warwickshire. He was living in a villa in St John’s Park, close to the sea, in Ryde on the Isle of Wight. William was married but his wife was living elsewhere. It made perfect sense for William Basing to be working in this position, as it was typical for a footman to progress to becoming a butler or valet after some years of experience. In a smaller household, both roles could be combined. William would attend at meals, look after the wine, supervise the other servants and take care of his master’s clothes, helping his master dress and shave. His master would be very reliant on him.

My next step was to see if I could trace William Basing in the 1861 census, which might place him in the London area. However, the only candidate in the 1861 census indexes on Ancestry was a 22 year old gardener, living in Basingstoke in Hampshire. Could he be the man I was seeking? Since this William Basing was unmarried at the time, and the William Basing I had found in the 1871 census was married, I decided to search the General Register Office (GRO) marriage indexes between 1861 and 1871. I found only two William Basing marriages between these dates:

| Quarter & Year | Surname | Forename | Registration District | Volume | Page No. |

| Jun 1861 | Basing | William | Kensington | 1a | 150 |

| Mar 1862 | Basing | William | Winchester | 2c | 123 |

via www.freebmd.org.uk

Either there were two individuals named William Basing, or the man whose marriage was registered in Kensington had been widowed soon after and married again in the registration district of Winchester. It seemed likely that the man who had married in Winchester was the same individual who I had found living in Basingstoke in the 1861 census. The marriage registered in Kensington was of particular interest, as it placed this William Basing in London, a few years prior to the birth of the twins in 1866. Luckily, an image of this marriage was available online from the London parish registers that have been indexed by Ancestry:

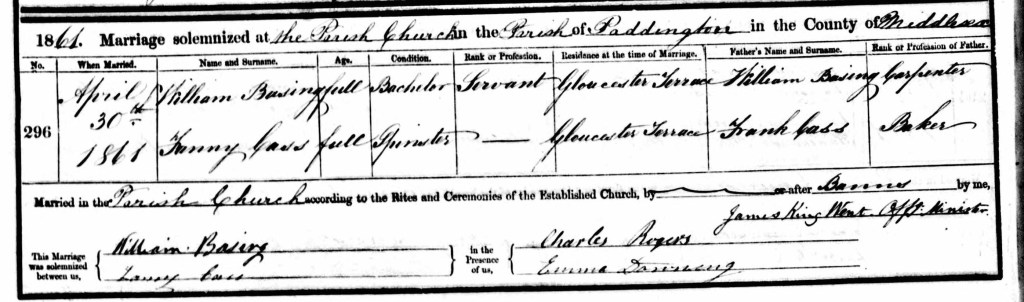

London Metropolitan Archives Ref. No. p.87/js/037

London Church of England Marriages and Banns 1754-1921 via www.ancestry.com

The marriage entry provided the information that William Basing, a servant, married Fanny Cass on April 30th 1861 in the parish church at Paddington. Since this William Basing was a servant, it looked likely that this was the marriage of William Basing, the butler and valet of Henry Gibb. His residence was recorded as Gloucester Terrace, Paddington. This street is close to Hyde Park and only a few miles west along the Old City Road from Southampton Street, Clerkenwell, the place of birth of Margaret England’s twins.

I decided to search the original 1861 census returns and track down Gloucester Terrace. There was a good chance that William Basing was working for someone who lived at Gloucester Terrace and indeed, that’s where I found him:

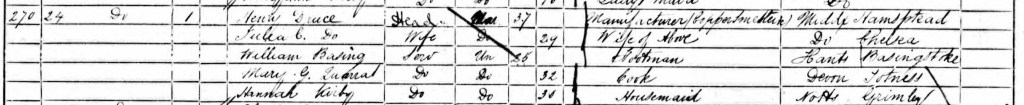

RG 9 11 98 13 via.www.ancestry.com

I was delighted to find that in this record, William Basing was described more specifically as a footman, which matched perfectly with the occupation given on the birth certificates of the twins of Margaret England. He was working for a man named Henry Druce, a manufacturer and copper smelter, who also employed a cook and a housemaid. It turns out that William’s surname of Basing had been mis-transcribed as Bading. When you cannot find someone in a census using online search engines, it is worth searching the original returns, particularly if you have an address.

I now knew that William Basing had been born in Basingstoke (in the area where his surname originated), around 1836. In fact, I found that his baptism had taken place on June 24 1838 in Old Basing, Hampshire. He was the son of William Basing, an agricultural labourer, and his wife, Sarah. (Incidentally, William Basing, the 22 year old gardener in 1861, was baptised the following year in Basingstoke, but he was the son of Thomas Basing).

It is clear that young William had decided to leave the Hampshire countryside and go to the city to make his career as a servant. He had managed to land the job of a footman. There were definitely attractions to being a footman. A footman earned more than an agricultural labourer and would have his board and keep thrown in so he could save his wages. There was also the possibility of earning generous tips from house guests.

A footman was an important manservant in upper class households, who denoted the luxury and status of their employer, so they had to be smartly dressed in livery when out and about. It was much preferred by employers if they were tall and handsome, so they could show off their elegant calves whilst wearing the traditional stockings, worn below knee breeches. William Basing must have fitted the bill. Even Mrs Beeton, in her guide, Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, published in 1861, wrote:

“the lady of fashion chooses her footman without any consideration other than his height, shape, and tournure of his calf”.

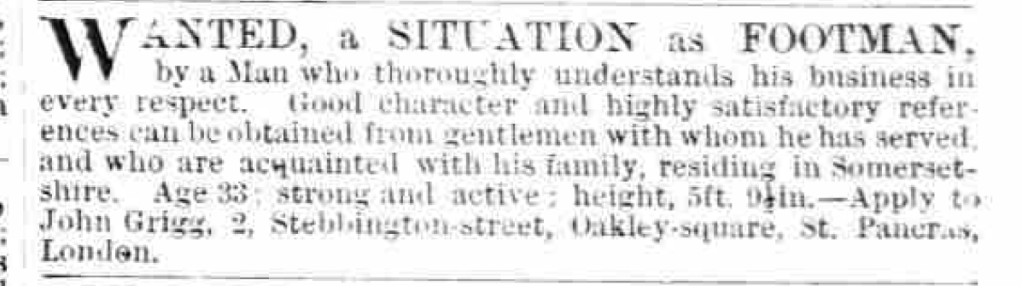

Originally, a footman was employed to run alongside his master’s carriage to make sure it didn’t overturn on the rough and rutted roads. He would also open and close the doors of the carriage for his Lord or Lady. By the 1860s, a footman would be expected to clean the shoes, carry the coal and hot water, trim and light the oil lamps, wind the clocks and open the door to visitors. He would also run errands for his master or mistress. In hierarchal terms, the footman served the butler. As such, he would lay the table, wait at the table during meal times and clear the table afterwards. He would also be responsible for cleaning the glass and plate under the supervision of the butler. Here is an advertisement in the classified section of the Morning Post newspaper, placed by a man named John Grigg who was looking for the position of a footman in 1864. Note that he includes in his advertisement the important detail that his height is 5ft. 9½ inches:

This photograph could well have been taken on his wedding day in 1861

I discovered that William’s wife to be, Fanny Cass, was working a few streets away from William’s workplace just prior to her marriage. Fanny was a 21 year old housemaid at 54 Porchester Terrace in Paddington. As you can imagine from the photograph above, William cut a dashing figure in his livery, tall, good-looking and energetic, and must have swept Fanny off her feet. However, the marriage of servants was frowned upon by employers who didn’t want servants to be distracted by spouses or children. It was rare for servants to be able to live together after they got married. Upon marriage, Fanny would have had to forfeit her position and rely on her husband, as he was now the sole breadwinner. The census returns revealed that Fanny had been born on the Isle of Wight, which explains why her husband was working there when the 1871 census was taken. Fanny had probably wanted to be close to her family and friends, especially with her husband barely at home.

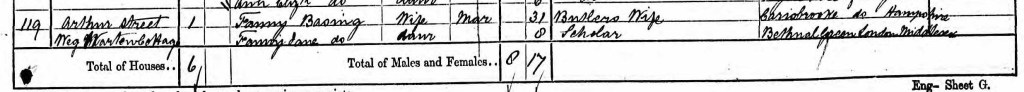

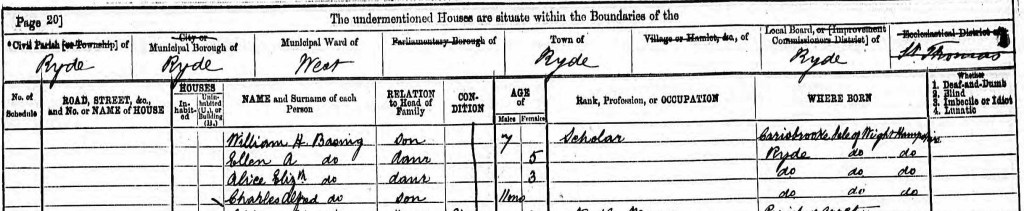

To find out more about William’s family, I searched the 1871 census for Fanny Basing and found that she was also living in Ryde, near to her husband’s place of work, along with their five children:

via www.ancestry.com

The eldest child, Fanny Jane, had been born in Bethnal Green in London ca. 1863, but the rest of the children had been born on the Isle of Wight. Fanny must have moved there by 1864, as her eldest son, William, was born in Carisbrooke that year.

For William Basing to be the father of the twin boys, he must still have been working in London in the summer of 1865. As a footman, he would have had the opportunity to leave the house, delivering letters and visiting tradespeople on errands for his master. On one of these occasions, he might have met Margaret England and struck up a secret relationship, particularly if his wife was many miles away on the Isle of Wight. When Margaret was pregnant, he may well have left London. Would she have known where he had gone? Even if she had known that he had gone to the Isle of Wight, how could she find him and get in touch? Did William even know of her pregnancy? Certainly, it seems unlikely that he contributed anything to the maintenance of his twins. William’s daughter, Ellen A. Basing was baptised on April 29th 1866 in Ryde, only six weeks after their birth.

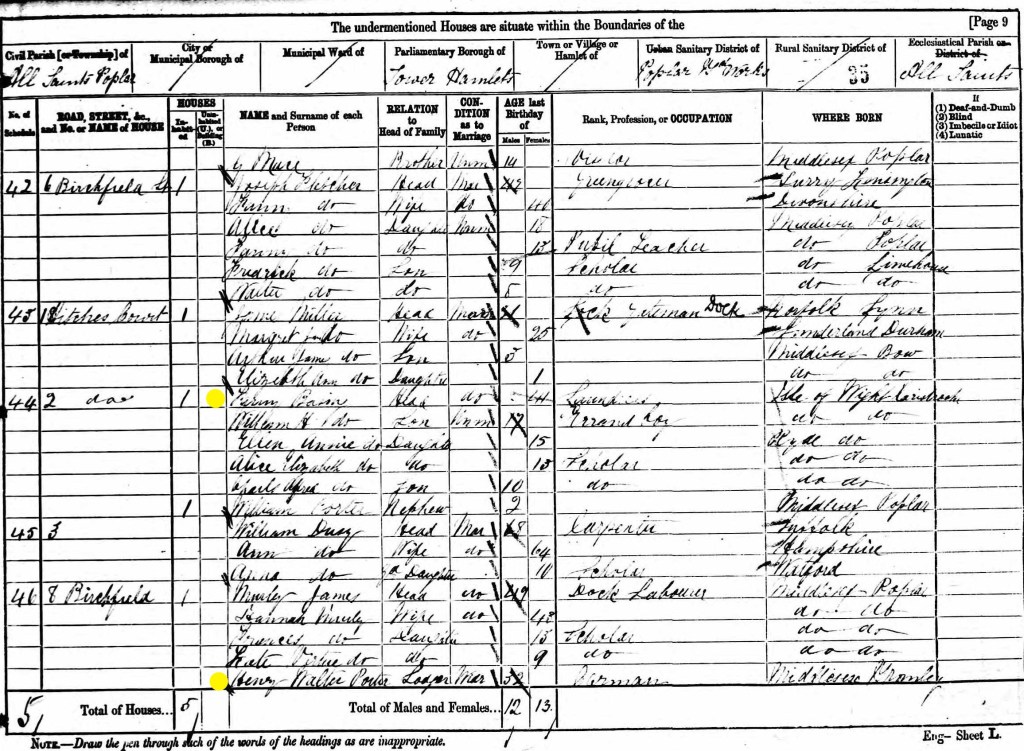

In 1880, William’s master, Henry Gibb, died, and if William was still in his service at this time, he would have had to seek new employment. There is no sign of William in the 1881 census but his wife Fanny and the children had moved to Poplar in the East End of London. The surname had been mis-transcribed as Basin in the census indexes:

RG 11 508 35 9 via www.ancestry.com

Fanny, though recorded as married, was on her own with the children, taking in laundry to help make ends meet. Why had she decided to return to London, rather than stay close to her family on the Isle of Wight? Had William deserted her? Had Fanny left him? It is interesting to note a certain man named Henry Walter Porter, who was living two doors along at 8 Birchfield Street. He was a 32 year old carman (a driver of a carriage), and although he was described as married, his wife had in fact died the previous year. His young son, William, described as Fanny’s “nephew”, was living with Fanny and her family. Henry Walter Porter was to become a significant person in Fanny’s life.

William and Fanny Basing obviously spent long periods apart and you can imagine that they lived in very different worlds. Fanny, devoted to her young children, was alone, managing the home, whilst William, living in a grand house, was devoted to meeting the needs of his master. He was probably good-looking and charming, (hence his job as a footman), and as a butler, maybe emulated the sophistication and manners of his employers. He also clearly had an eye for the ladies. Was Fanny aware of William’s adultery earlier in their marriage? In these circumstances, it is perhaps not surprising to learn that William and Fanny’s marriage had deteriorated to such an extent that in February 1883, Fanny had had enough. She contacted solicitors and set out to get a divorce. On what grounds? – adultery, coupled with desertion.

Next time, find out about the divorce proceedings and what happened to William Basing next.

© Judith Batchelor 2020

Another intriguing story you have unravelled here with some great genealogy detective work, we can never know the exact circumstances that presented themselves to William, was he a bad boy or a good man, we cannot be certain, looking forward to the next instalment

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have to say that the next instalment doesn’t paint William in a very good light but though he may not be blameless, I can see how difficult it must have been for married servants. They didn’t really have a home life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s always so difficult to judge the decisions made all those years ago, I have discovered one previously that I couldn’t help making a judgement on and I am currently wrestling with another and again it’s hard not to make a conscious judgement

LikeLiked by 1 person

I guess you make a judgement based on the evidence but with the important caveat that the evidence is probably incomplete and may not give you the full picture.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think because we are Genealogists our natural instinct tells us that we need to prove something beyond reasonable doubt as a fact. Sometimes we just have to accept that we can’t always prove every single theory.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very cool that you were able to track down the divorce records…so often people at the lower end of the social scale just decided to live apart and often committed bigamy when they married again. Very interesting story so far 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person