After my father passed away in 2014, I inherited a miniature chest of drawers that had belonged to my mother. It had stood on her dressing table for as long as I could remember, filled with useful things such as hair grips and safety pins. I always thought it was rather attractive, and from the photograph, you can see that it is a fine piece of craftsmanship. What makes it particularly special is the fact that it had been given to my mother as a wedding present in 1949, and the craftsman, Horace Hinton Uphill, was her relative. Horace Hinton Uphill has a rather interesting story so I thought I would share it with you and invite you to enter the world of dolls’ houses and their Lilliputian contents.

crafted in oak ca. 1949 by Horace Hinton Uphill (1898-1976) Author’s photo.

Horace Hinton Uphill, affectionately known as Hodge, was born in Wilton in Wiltshire in 1898, the eldest son of James Hinton Uphill and his wife Florence, nee Hazard. A brother, Donald Gordon Lee Uphill, was born in 1900, but died in infancy, and another son, Kenneth Lee Uphill, who was born in 1903, completed the family. James Hinton Uphill described himself as a cabinet maker and joiner on the 1911 census form:

via http://www.ancestry.co.uk

The Uphill family home was 20 West Street in Wilton, where James Uphill had his carpentry workshop. He is listed as a carpenter and joiner in a series of directories stretching from 1898 to 1927, latterly being described as a cabinet maker. I have also found a number of advertisements for his business in the local newspaper. It is clear from these that he was a man of many talents, offering his services as an undertaker, a cabinet maker, a picture framer and an upholsterer. His work as an undertaker no doubt provided him with a steady income, whatever the economic climate.

via http://www.google.com/maps – August 2018

Hodge was to spend all his life in the Wilton, only moving away from the town for a few years when he served on the Home Front during World War I. Shortly after he turned 18 in 1916, he had joined the Army Service Corps, which was in charge of transportation, air despatch and barracks administration. It was also in charge of supplying food, clothing and technical and military equipment. On his attestation form, Hodge gave his occupation as a motor driver so he may well have drove a hearse for his father. At the time, the Army Service Corps was actively recruiting motor drivers, as can be seen from this poster of 1915:

In February 1917, Hodge was compulsorily transferred to the 26th Training Reserve Battalion before moving to the Royal Army Medical Corps in December 1917, in which he continued until his discharge in 1919. According to a family story, he also served as a batman to Army officers. One day he was with the officers when they were on an otter hunt with their hounds. Since Hodge was a gentle person and a naturalist, he was desperate for the otter to escape. Using his wits quickly, he created a fire as a way of distracting the dogs away from the otter’s scent.

In 1930, Hodge married Dulcie Irene Gale, the first cousin of my grandmother, Margaret Bullock. How they met is a rather charming love story. Horace had many interests and hobbies, one of these being cinematography. In those days, silent movies would be shown in village halls and one evening, Horace had arranged for a film to be shown at the Wyvern Village Hall in Wylye. Dulcie, who was musical, had the job of playing the piano accompaniment and their eyes met! In order to spend time together whilst they were courting, they would go walking on the Downs between Wilton and Wylye, meeting halfway between their homes. One day, Dulcie was rather later in arriving at their prearranged rendezvous and to her horror, saw Hodge lying prone on the ground, as if he were dead. It was at this moment that she realised that she loved him and soon after this, they were engaged and married. They had no children of their own but were devoted to one another for the rest of their lives.

© Copyright Andy Gryce

Hodge and Dulcie set up home in Wilton and in the 1939 National Register, they were living on Victoria Street, just round the corner from Hodge’s childhood home of 20 West Street. Hodge’s father, James, had died earlier that year, though his mother, Florence, lived until 1952. Hodge was described as a cabinet maker and an undertaker in the National Register. He had taken on the business of undertaking from his father, and conveniently, he also lived a short distance from the Wilton parish church of St Mary and St Nicholas on West Street.

It would seem from these records that Horace Hinton Uphill was a successful cabinet maker and undertaker in a small Wiltshire town, who had taken over his father’s business. However, this only tells a small part of his story, as he was also, in fact, an exceptional craftsman of miniature furniture. His work is highly collectable today and renowned for its quality and finesse. From time to time, miniature furniture that he made comes up for auction. Here are some examples of his work, donated to Salisbury Museum by his wife, Dulcie, after her death in 1977. They are on display in the museum today:

In the catalogue of Salisbury Museum, these pieces are described as “miniature” furniture, rather than doll’s house furniture but his pieces are especially prized by dolls’ house enthusiasts.

In July 1998, Sally Howard-Smith wrote an article on Horace Uphill, which appeared in International Dolls’ House News, a now defunct magazine. This is what she had to say about him:

Father and son were both mild eccentrics. The father had an obsession with Scotland (though Wiltshire born and bred) and sometimes toured the villages in full Highland dress to play the bagpipes. Horace displayed an early interest in ecology and the environment, and in wildlife photography, which he could pursue in Grovely Woods, where his ashes have been scattered. By inclination he was a vegetarian and believed himself to be a physic.

According to Sally Howard-Smith, Hodge employed two ladies on three year apprenticeships to assist him in his miniature work. The apprentices were paid thirty shillings for a forty-seven and a half hour week and it was their job to make the stamps and dies for handles, and their own tools for turning small legs for cabinets and chests.

As early as the 1920s, though still a young man, Horace was achieving some notable success with his miniature work. There had long been a fashion for creating beautiful dolls’ houses, known as baby houses, as expensive gifts. The craze began with the German aristocracy before spreading to the middle classes, and then to Holland. They were custom built with a cabinet frame and inside were individual rooms full of beautiful hand-crafted miniature furniture, designed to be enjoyed by adults, rather than children. Dolls’ houses became popular in England too from the late 17th century. By the Victorian period, with industrialisation, doll’s houses were beginning to be mass-produced and designed more for children. Nevertheless, adult enthusiasm for dolls’ houses and their miniature contents remained unabated. It reached a heyday in the 1920s’ and 1930s’, with the unveiling of two of the greatest dolls houses in the world, Titania’s Palace and Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House. Horace Uphill was certainly commissioned to create miniature furniture for Titania’s Palace and in all probability, Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House too.

Titania’s Palace was commissioned by Sir Nevile Wilkinson in 1907. Sir Nevile had many roles; he was a British Army Major, an artist, and a writer, as well as the Ulster King of Arms, the chief heraldic officer of Ireland, from 1908 until his death in 1940. Despite having the physique of a giant, at over 6′ 5″‘, he loved all things miniature and wanted to design a magical doll’s house for his young daughter, Guendolen. One day his young daughter told him that she had glimpsed fairies running under the roots of a sycamore tree in a wood on their country estate, Mount Merrion, near Dublin. This inspired him to create a beautiful palace that would be suitably fit as a home for the King and Queen of Fairies.

Sir Nevile commissioned James Hicks & Sons, Irish cabinet makers, to construct the cabinet, which stands 4′ 11” tall and is built to a 12:1 scale, in the style of an Italian Renaissance palace. As Nicola Lisle writes in “Life in Miniature: A History of Dolls’ Houses“, it was designed as a showpiece: “it was intended to impress, to surprise, to enthral and to entertain”. Leading craftsman of the day were to help fill each of its sixteen rooms with all manner of treasures. Sir Nevile also acquired other precious miniatures, some of considerable antiquity, to add to its charms. There had long been a tradition of craftsman creating miniatures as samples of pieces of furniture, before their full-sized counterparts had been constructed. The attention to detail is extraordinary, with every piece an exact miniature replica. For example, in the morning room are seventy-five books, all bound in calf leather, of various popular works. Sir Nevile contributed his own miniature mosaics and the eye-catching belfry was designed by Sir Edward Lutyens, the well-known British architect. In all there are over 4000 individual pieces. Horace Uphill is listed in the catalogue as the maker of the carved bed in Oberon’s Dressing Room and the “remarkable” fine inlaid William and Mary cupboard in the Dining Room. A picture of this can be seen below:

Sir Nevile had married the eldest daughter of the Earl of Pembroke whose seat and family home was Wilton House, in Wilton. Perhaps Sir Nevile had got to hear about Horace Uphill and his work during a visit to Wilton. An earlier dolls house that he had created, Pembroke Palace, which replicated much of the interior decor and the portraits and paintings of Wilton House, had been opened for exhibition at Wilton House in 1908 by Princess Alexandra. Perhaps Hodge’s father, James Uphill, had created some furniture for it. After a major restoration project in 1982, it can be seen on display today at Wilton House.

Titania’s Palace took fifteen years to complete and was officially opened by Queen Mary in London on July 8th 1922 (when Guendolen was 18), at the prestigious Women’s Exhibition, under the auspices of the Daily Express. It was known that Queen Mary was a huge fan and collector of what she called “tiny craft”. Sir Nevile’s vision was that Titania’s Palace, as well as being enjoyed and admired by children and adults alike, would be an instrument in raising money for children’s charities. The dolls’ house was an immediate success with seventeen thousand visitors paying their respects to the Fairy Queen in sixteen days and over £420 being donated to children’s charities. It then went on tour all over the country and indeed, the world, raising an estimated £150,000. Sadly, due to the loss of its permanent home in Ireland, it was reluctantly sold by the family in 1967 but remained on show to the public in Wookey Hole in Somerset and then in St Helier, Jersey, whilst in the hands of its new owner, Olive Hodgkinson. It was to come up for auction again in 1978, after the death of Olive Hodgkinson. Despite strong Irish interest, a mysterious bidder won Titania’s Palace with a winning bid of £131,000. The new owner turned out to be none other than Legoland! Titania’s Palace was put on display at Legoland in Denmark where it remained until 2007. Subsequently, it has been on loan to Egeskov Castle in Denmark, where it can be viewed today.

Photo courtesy of Beth – Flickr Stream

The wonder of Titania’s Palace really has to be seen to be believed. In lieu of visiting in person, this YouTube video captures some of its magic.

Just before Titania’s Palace had been completed, Sir Nevile heard that a rival dolls’ house was under construction, designed by Sir Edward Luteyns himself. He had had to speed up the work on Titania’s Palace to ensure that his dolls’ house wouldn’t be eclipsed. This new dolls’ house had been commissioned for Queen Mary by her friend, Princess Marie Louise, who was a cousin of Queen Mary’s husband, George V. The dolls’ house was to be a gift from the nation in recognition of the part Queen Mary had played in lifting the country’s spirits during the long years of World War I. It was to be showcase of British workmanship, with British craftsman commissioned to create all of the exquisite miniatures. None other than Gertrude Jekyll was to design the garden. Nicola Lisle in “Life in Miniature: A History of Dolls’ Houses” describes it as “one of the greatest creative triumphs of the twentieth century”. “Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House is a glorious edifice that brings together all that is best about Britain at the time in one magnificent package”. Queen Mary’s Dolls House took three years to complete and in just seven months, it was seen by 1.5 million people when it was exhibited in 1924. The Times called it a “a miracle in miniature”. Everything was authentic and worked, from the electric lighting to the running water. Many of the leading lights of the day were asked for contributions of their work, so the house, for example, contains original miniature books written by writers such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle or A.A. Milne. Similarly, there are musical scores and art works by the most popular composers and artists of the time. Lisle describes it “a vivid slice of social history, a visual statement on Britain in the 1920s”.

Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House is now part of the Royal Collection and is on display at Windsor Castle. More photographs and a video about its conservation can be viewed here.

Photo courtesy of Rob Sangster – Flickr Streamd

It is very probable that Hodge contributed to Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House, given his work on Titania’s Palace and contemporary reputation. I am currently seeking proof of his involvement from the archivists at the Royal Collection. According to Sally Howard-Smith, two miniature pieces were later purchased from Hodge by Queen Mary directly. They are part of the Royal Collection at Sandringham: a William and Mary triple hooded tallboy in walnut and a William and Mary double door secretaire in walnut, yew, and tulipwood, both dated 1949 (the year my own chest of drawers was made).

Horace is also renowned as the creator of both the room and the furniture for the William and Mary Parlour, part of the Carlisle Collection created by Mrs Carlisle. Kitty Carlisle was an avid collector of miniature furniture from the 1920s for over forty years and was a good customer of Hodge. Her idea was to create a series of sixteen rooms, each one with a different period setting. They were filled with both antique and modern furniture, on a scale of one-eighth, and diminutive accessories. In 1953, Hodge also made the games tables for the Regency Games Room. When the rooms were finally completed in 1969, they contained over 10,000 items. The following year, in 1970, her collection was donated to the National Trust and its home is at Nunnington Hall in Yorkshire. Further information on the Carlisle Collection can be found here, on the National Trust website.

© The National Trust

Over the years, Hodge continued to make fine pieces of miniature furniture on private commission. Hodge and Dulcie also opened their own antique shop on the premises of Hodge’s father’s business at 20 West Street, Wilton. As an acknowledged expert in his field, Hodge made an appearance on BBC Television in 1949 on a popular magazine show called Picture Page. Two hour-long editions of the show were broadcast every week. They included a range of interviews with well-known personalities and features about a range of topics. Hodge also appeared on television a further six times in 1952 on a show called Leisure and Pleasure. Here is the listing for the show in the Radio Times – January 8th 1952:

Horace Uphill, a cabinet-maker famous for his miniature models, shows some William and Mary pieces, and explains how to recognise the characteristics of this period.

Hodge is also believed to have appeared with Arthur Negus, the antiques expert, on the television series, Going for a Song, (1965-1977).

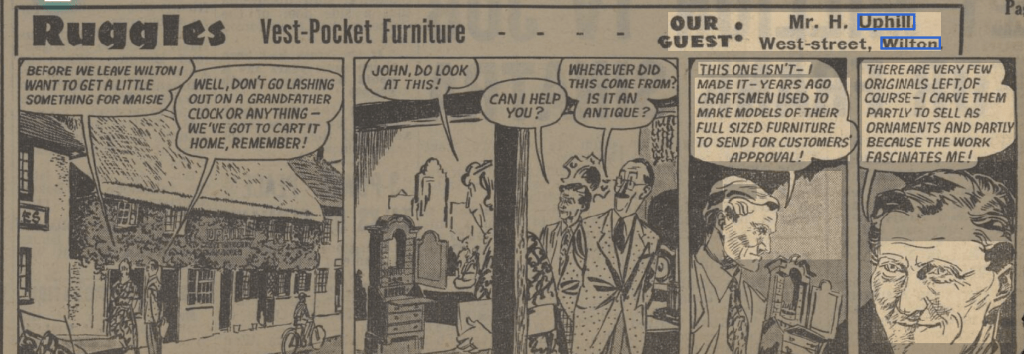

Television brought Hodge and his work to a larger audience. I found this wonderful Ruggles comic strip depicting a couple visiting his shop in the Daily Mirror newspaper in 1950:

Since I have no photograph of Hodge, it is wonderful to have this drawing of him instead.

Over the years, my Aunt Nan and other family members visited Hodge and Dulcie at their home at 3 Victoria Street, Wilton. They were always kind and hospitable hosts and their home was like an Aladdin’s cave, full of antique furniture and beautiful curios, all tastefully and artistically arranged. Hodge had his own workshop and a garage at the end of the garden. Though comfortably off, Hodge clearly created his masterpieces primarily for the joy that the work gave to him, sometimes charging very little considering the hours spent. Dulcie was the more business-like of the two so they made a good partnership. Both Hodge and Dulcie are fondly remembered.

Hodge died in 1976 and left everything to Dulcie but she was lost without him, dying little more than nine months later. In her will, Dulcie left all Horace’s woodworking tools, presses and unfinished items of miniature furniture to the Searchlight Workshops of Mount Pleasant, Newhaven, East Sussex, a charity that supports adults with physical and learning difficulties, which is still going strong today.

It is remarkable to think that Horace Uphill had a hand in at least two and maybe three of the greatest dolls’ houses of the twentieth century. All three played an important role in raising money for children’s charities whilst at the same time, providing pleasure and fascination to thousands. In our current age of cheap, manufactured goods, churned out in factories, you cannot fail to appreciate the beauty of these hand-crafted miniature masterpieces. Each one was made with loving care and the utmost attention to detail, in order to bring delight and joy. Although too big to fit in a dolls’ house, I treasure the miniature chest of drawers that is now in my possession, made by Horace Hinton Uphill, the master craftsman and creator of miniature furniture.

I leave this story with a challenge. Perhaps you also have a treasure in your home that has been passed down in the family. Maybe you know who it once belonged to and its history, but is this information going to be lost in the future? What are you going to do to preserve the story, as well as the artefact or treasure? It’s something to think about.

© Judith Batchelor 2021

A really fascinating story and what marvelous treasures this craftsman created! Your family is fortunate to have the heirlooms and the story (thanks to you).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Marian! Knowing the story behind the heirloom makes it even more special.

LikeLike

I met Uncle Hodge and Aunty Dulcie just once, it must have been in the late 1960s/early 1970s. The first thing Dulcie said to me was that I had my (and therefore your) Grandfather’s eyes. I remember Hodge said he was experimenting with filling clear plastic bags with gas and releasing them just after sunset. They would be invisible until reaching a height where the sun’s upward slanting rays would make the underneath glow red. He said the best one he had done was a bag that a suit had come in! At around that time I believe the Wilton area was the UFO capital of England, and I’ve always wondered whether Hodge was the cause of so many sightings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a wonderful memory! It really epitomises the type of man Hodge was, with his curious mind and interest in all sorts of subjects. I wish I could have met him too.

LikeLike

Tucson, Arizona has a miniature museum that I’ve been too. It’s quite fascinating. Having seen so many miniature pieces, I can appreciate Hodge’s talent. Beautiful work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting that there is a miniature museum in Tuscon. I think the fascination with all things miniature is universal.

LikeLike