On the broad plateau of the chalk downs of North Wiltshire, you will find the handsome church of All Saints, Yatesbury. Yatesbury, a tiny village of around 150 souls today, lies just north of the current A4 road that runs between Calne and Marlborough. If you decide to pay a visit, and wonder through the peaceful churchyard, you might notice an attractive Celtic cross, under the spreading branches of an ancient yew tree. Now covered in lichen, matching the honey colour of the church itself, the inscription has long been illegible. Faintly, the year 1847 can be made out. Who does this cross commemorate, and what story does it tell?

via http://www.wikipedia.org –

Brian Robert Marshall – CC BY-SA 2.0

Some months back, I wrote an article called the The Good Samaritan, based on a newspaper report I had found about the tragic death of a young boy named George Beale. George’s father, Samuel Beale, a cooper of Gray’s Inn Road, St Pancras, had fallen on hard times and poor health had meant that he had been unable to work. The situation had become desperate and young George had been sent away from home to start a new life at sea. However, the ship had sailed without him from Exmouth and poor George had no choice but to start on the long journey home, walking from Devon to London. On the way, just outside Calne, Wiltshire, he encounters the Reverend James Money-Kyrle, the rector of Yatesbury, who passed him on the road in his horse and trap. George must have been a pathetic sight, dressed in a tattered sailor’s costume, his feet were bleeding and covered in chilblains. He was tired, hungry and distressed. The Reverend stops and after hearing his story, he gives George some money and tells him to call at the Rectory in Yatesbury, providing him with a note to give to his housekeeper. He is the epitome of the Good Samaritan. Sadly, poor George never makes it to the Rectory. He loses his way and although some individuals do their best to help him, not everyone comes out well in the story. Meanwhile the Reverend makes enquiries in London and traces George’s parents. He visits them and verifies George’s story. He wants to help George and find him a position but when he arrives back home, it is too late, George had been found dead in a ditch. The kindly Reverend pays for George’s funeral and says that he will erect a memorial to George.

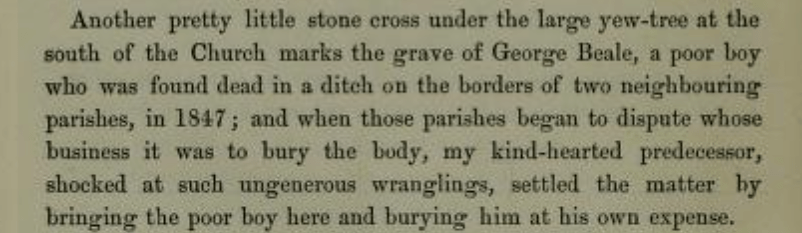

Since then, I have been wondering if the memorial to George Beale was still in existence today. I was confident that the Reverend had kept his word but although monumental inscriptions from the churchyard at Yatesbury had been transcribed some years ago, by volunteers from Wiltshire Family History Society, there was no reference to George Beale. However, due to the kindness of a reader, I have now found proof that the Reverend Money-Kyrle did indeed erect a monument to George in the form of a small cross. The evidence was found in a issue of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, in an article written by the Reverend Money-Kyrle’s successor, the Reverend A.C. Smith:

Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine 1854-1891, Vol. 67, Part B

-Natural History Museum, London via http://www.internetarchive.org

Two further readers then volunteered to visit the churchyard and were able to identify the location of the cross today. Although the inscription cannot be deciphered without some further work, the year 1847 can be discerned in the centre of the cross:

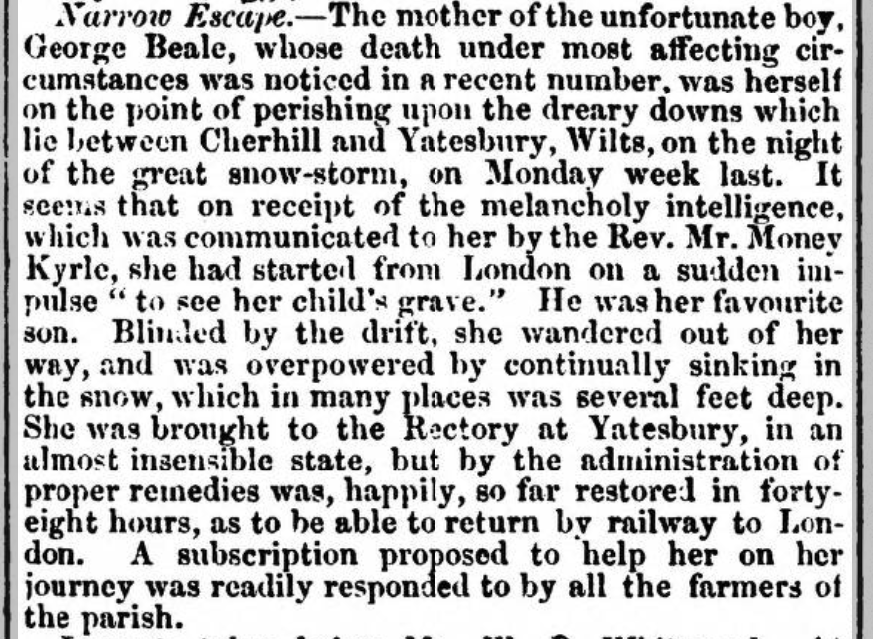

Furthermore, in another twist to the story, the local newspaper reported that George Beale’s mother came all the way from London to visit her son’s grave, shortly after his death. In doing so, she nearly perished herself:

via http://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

George Beale was buried on February 3rd and from the newspaper report, it seems that less than two weeks later, on Monday February 15th, his mother, Sarah Beale, had travelled to Yatesbury. George’s father, by this time, was no doubt too ill to travel, as he died less than a month later on March 10 1847. To get to Wiltshire from London, she must have taken the train, but the nearest station to Yatesbury was probably Chippenham: the station there had opened six years previously in 1841. Yatesbury is around twelve miles distant and during the winter, it was difficult to reach because there were no paved roads there, only muddy tracks. George’s mother had probably taken the main road from Chippenham to Calne, walking eastwards until she reached Cherhill. She then had to leave the main road to reach Yatesbury, all in the middle of a snowstorm. The downs would have been very bleak with strong winds and blinding snow. Where was she intending to find shelter? It seems that it was a spur of the moment decision by a mother blinded by grief after the death of her beloved son. Did she feel responsible for what had happened to George? Maybe she felt that he would never have died if he had not been sent away from home. To add to her grief, her husband was sick and dying and they had no money. After falling in multiple snow drifts, it appears that she was brought in an insensible state to the Rectory, close to death. Once more, the Reverend was the Good Samaritan. He took care of her at the Rectory for two days until she had regained her strength. Local farmers also rallied round and paid her train fare back to London.

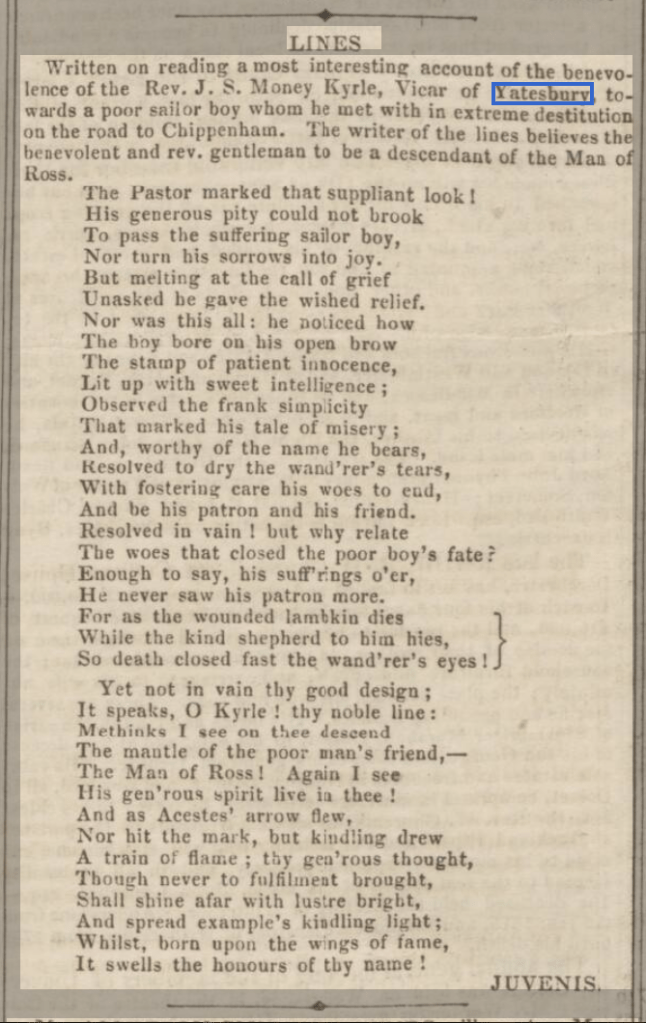

News of the Reverend’s kindness obviously spread locally, as his actions inspired “Juvenis” to compose a poem about him that was printed in the local newspaper the following month. The author describes him as a descendant of “The Man of Ross”:

"Methinks I see on thee descend, The mantle of the poor man's friend - The Man of Ross!"

via http://britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

I had never heard of the Man of Ross before, but I discovered that he was a man called John Kyrle of Ross on Wyre, Herefordshire, (1637-1724) who was renowned for his philanthropy. From his early twenties, after inheriting the family estate, he used his fortune for the good of the local community, being generous to the poor and taking a lively interest in the welfare of the town. He was eulogised in verse by the poets Alexander Pope and Samuel Coleridge so clearly, the writer of the poem in the newspaper had taken inspiration from them. By looking at Burke’s A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Extinct and Dormant Baronetcies, I was able to confirm that the Man of Ross was indeed a distant relation of the Reverend James Stoughton Money-Kyrle.

Looking further into the background of the Reverend James Money-Kyrle, I discovered that his father, the Reverend William Money-Kyrle, had been the previous rector of Yatesbury from 1800 until 1843, when his son succeeded him. It was also in 1843 that his father had changed his name by Royal Licence from Money to Money-Kyrle, when he inherited the family estates from his elder brother, James Kyrle Money, who had died childless. With this the Money baronetcy became extinct. The Reverend William Money-Kyrle and his wife, Emma, née Down, had had seven sons altogether, who variously served in the Army, the Church, the Law, or went to India to trade. They also had one daughter. James Stoughton, or ‘Stoughton’, as he was known in the family, was the fourth son, born on October 13 1813 in Clifton, Gloucestershire. Since he was a clergyman, he would have had a university education, so I was able to find biographical information on him in Venn’s Alumni Cambridgenses:

via http://www.internetarchive.org

Although Stoughton married in 1839, I have found no evidence that he and his wife, Rosa, née had any children. Stoughton became the rector of Yatesbury in 1843, a post that he held until his death at the early age of 38 in 1852. Ordained as a deacon in 1841 and a priest in 1842, he had previously served as a curate in Alderley, Gloucestershire.

The lineage of the Money-Kyrles can be seen in the pedigree chart below. The families of Ernle and Kyrle were united in 1674 by the marriage of Sir John Ernle (c.1647-1686) of Burytown, Highworth, Wiltshire, and Vincentia Kyrle (1651-1683) of Much Marcle, Herefordshire. Constantia, their daughter, settled her estates upon Colonel James Money, son of her first cousin, Elizabeth (nee Washbourne), who had married Francis Money of Wellingborough, Northamptonshire. (This resulted in a lengthy lawsuit). The family had estates at Whetham, Calne and Homme House, Much Marcle, Herefordshire:

A history of the borough and town of Calne, and some account of the villages, etc., in its vicinity p. 184 by A.E. Marsh (1904) via http://www.internetarchive.org

There is a big archive on the Money-Kyrle family at the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre. This includes some information specifically on James Stoughton Money (‘Stoughton’) (1813-1852), who ended his life as James Stoughton Money-Kyrle. He is known to have been interested in genealogy, archaeology and antiquities. Indeed, he had been made a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. In his early years, until 1835, he had worked for the East India Company. It is also recorded that he was plagued by constant financial problems. There are some letters in the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre from his father, Rev. William Money-Kyrle, that mention Stoughton’s financial difficulties (WSRO 1720/569). There is also correspondence from his brother, William Money-Kyrle, concerning the settlement of Stoughton’s financial affairs after his death. (WSRO 1720/572). No doubt an examination of the documents in the archives would shed more light on his circumstances.

I was delighted to discover that a painting of Stoughton exists, which a current member of the family has kindly given me permission to share:

Note the small coats of arms of Money (left) and Stoughton (right) in the top right-hand corner of the painting, evidence of Stoughton’s lineage and no doubt his interest in genealogy:

Money Family of Homme House, Much Marcle, Herefordshire: chequy argent and gules on a chief sable three eagles displayed or Stoughton Family of St John's Warwickshire: azure a cross engrailed ermine

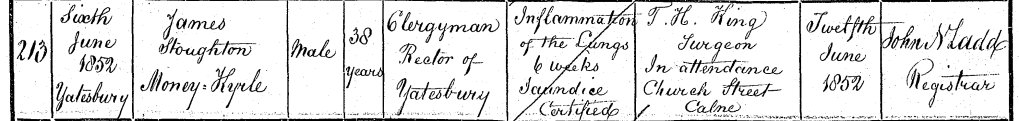

Strangely, I haven’t been able to find Stoughton or his wife, in either the 1841 or 1851 censuses. In 1851, a curate and his family are the only clergy recorded at Yatesbury. I have also found no evidence that Stoughton left a will. Perhaps his death was sudden and his financial affairs were complicated. Although I have found some notices of his death, reported in the newspapers, I haven’t discovered an obituary for him either. Given the family’s social status this seems surprising. His burial is recorded in the Yatesbury registers on June 12 1852 yet there is no monumental inscription for him in the indexes compiled by Wiltshire Family History Society. Perhaps, like the monument to George Beale, it has not identifiable if the inscription is no longer legible. I ordered a copy of his death certificate to see what had caused Stoughton’s early demise:

Stoughton had died of inflammation of the lungs of 6 weeks and jaundice. Perhaps it was a bad bout of bronchitis that he couldn’t shake off, in an age when antibiotics had yet to be discovered.

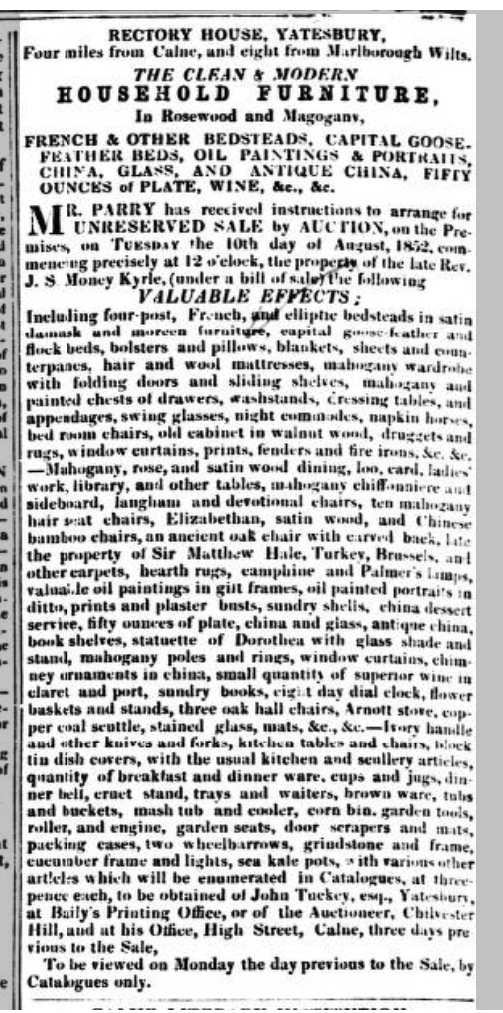

Although I had found no obituary for Stoughton in newspaper records, I did discover a notice of sale for all the contents of the Rectory at Yatesbury, after his death:

via http://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

https://media.onthemarket.com/properties/1436572/doc_0_2.pdf

When Stoughton was living in Yatesbury, the Rectory was a brand new stone house. His father had begun the building work in 1832 and the house was completed in 1843, just in time for Stoughton’s appointment as rector. Why were all the contents of the Rectory in Yatesbury being sold after Stoughton’s death? Was money needed to pay off his debts? One wonders how he had got himself into such a bad financial position, given his wealthy family background. Had the house become an expensive burden to him? The sale catalogue gives a fascinating glimpse into the rooms of the Rectory and gives you a mental picture of Stoughton’s personal possessions. You wonder how his widow felt, having to leave her home and with it, so many memories of their life together.

The first member of the family to hold the advowson of Yatesbury, (the right of choosing the rector), was Stoughton’s forebear, Sir John Ernle of Whetham, Calne (d. 1647). According to the Victorian County History of Wiltshire, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/ the right of advowson was passed down through the Ernle, Money, and Money-Kyrle families until 1853. After Stoughton’s death, his brother, William Money-Kyrle, sold the advowson of Yatesbury to the Reverend A. C. Smith. Advowsons could be a valuable commodity as the incumbent was entitled to the income from tithes. These had been commuted to payments under the Tithe Commutation Act of 1836. The Victorian County History states that in Yatesbury, tithes were valued at £510 in 1839 when they were commuted, one of the higher yields in the county. Glebe land in the parish, which was owned by the church, also provided additional income for the rector. There were 27 acres of glebe land in Yatesbury in 1839. Presumably the advowson was sold because it would provide some funds to settle Stoughton’s affairs. In addition, perhaps no one in the family wanted to take on the position of rector. The funds may have been used, (along with the proceeds from the sale of the contents of the rectory), to support Stoughton’s widow, Rosa. However, since she was from a wealthy family, (her father was a banker), one wonders if she really was in need. She married again two years after Stoughton’s death.

Although Stoughton came from an illustrious family background, he was the fourth son of seven and seems to have led a relatively obscure life. After a short career with the East India Company, he had entered the church and taken over the position of Rector of Yatesbury from his father in 1843. Sadly, despite his privileged background, it seems that he was beset by financial problems. Since he died young and left no heirs, in many ways his life has been overshadowed by more prominent members of his family. He left no will, nor can I find an obituary for him or any surviving monument that commemorates his life. He could very easily fade into obscurity and be all but forgotten today yet in the story of George Beale, he has left a noble legacy. A picture emerges of a thoroughly decent man who cared for the unfortunate, the stranger, and those in need, following Christ’s teaching. I am sure that his kindness was not forgotten by the family of George Beale, particularly his mother, who in turn, had need of the good Reverend’s help. I can’t help but feel that in his short life, James Stoughton Money-Kyrle did a lot of good and was a caring and compassionate rector. In spite of his early death, memories of him must have burned brightly for a long time in the hearts of his parishioners.

© Judith Batchelor 2021

For further information on the story of George Beale and the Reverend James Stoughton Money-Kyrle, can be found in The Good Samaritan.

Brilliant that you found a portrait, feel like I know the man.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was really thrilled when the owner gave me permission to use it for my piece.

LikeLike

Lovely write-up, Jude, and great to know a bit more about the family! Whetham is also a lovely looking house (from what you can glimpse of it from the road!). When I read your first post about George Beale, I wondered how he had come to be rector at Yatesbury – and finding out that there was the family connection to the church, as well as to the Calne area in general is fascinating!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it was interesting to discover that the family had been installing rectors there for literally centuries. I think Yatesbury provided an above average income for a rector in the county but perhaps it was a struggle to maintain a certain lifestyle.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Congratulations Jude – a wonderful piece of research. Sad at times. but uplifting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, I feel the same.

LikeLike

Wow- such a touching story for so many reasons. Poor little George – a horrible tragedy for that family…little wonder his mother travelled to see his grave. That poor woman.

As for James, he sounds a thoroughly decent man and given his childless state, one might also imagine he had an even softer spot for children, hence his extra care for George. So sad that James too died young. And surprising no-one wrote an obituary.

Interestingly enough, the wife of my third great-uncle William, Mary Bull, and her family lived in the Calne area…I imagine they heard all of this first-hand.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed, James does sound as if he was a thoroughly decent man with a real caring heart. Obviously news of the tragedy concerning poor George Beale must have caused a sensation locally. It is very likely that your family (and mine), knew all about the story. At least there was a poem dedicated to the rector, even if I haven’t found an obituary for him.

LikeLike

You never know, it’s always a possibility! My great grandfather, Albert Bullock, when he retired, bought his house from a Mr Bull. He joked that it was “Out with the Bull and in with the Bullock”! Different area of Wiltshire though.

LikeLike

LOL!

LikeLike

I much enjoyed reading your article – very enlightening. Many thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful, thank you!

LikeLike