Previously, in Ancestors who were Blind, I looked at how our blind ancestors might have lived with their disability, specifically looking at the life of my husband’s ancestor, Hannah Lilian Woodcock. In this article, I will be looking at ancestors who were deaf, illustrated by the life of my deaf relative, Maria Batchelor (1827-1903). At this time, deafness did not just mean hearing loss, it also meant lack of speech. You will therefore find that a deaf person was often described in the records as deaf and dumb, or as the century progressed, deaf mute, offensive terminology which would not be used today to describe non-speaking deaf people. Whilst blindness generally elicited much sympathy in society, in Maria’s lifetime, deafness had more negative connotations. Deaf people were thought to be irreligious, as they could not hear the Word of God. In addition, it was believed that there was a strong connection between reason and speech, so if a deaf person could not speak, they were not intelligent. It must have been a harsh world if you were deaf; you had to deal with society’s prejudices as well as the impact of your disability on everyday life. Medical help for deafness was limited and often quackery was practised. Horrible treatments included drilling holes in the jaw, or pouring noxious substances into the ears. These caused horrific injuries, even death. With the lack of sound medical treatment and only primitive audio enhancing technology, (which was was very expensive), most people had to live with their deafness and adapt to life as best as they could.

Census records are one of the best sources of information on deaf people in Victorian Britain. From the 1851 census onwards, a disability column was introduced and it was to be reported whether a person was deaf and dumb. The detailed 1861 census reports, which can be found on the Vision of Britain website, are an excellent source on the number of deaf people in Britain at this time: https://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/census/EW1861GEN/11. In 1861, just over 12,000 people were recorded as being deaf and dumb, around 2000 more than in 1851. However, because of the associated stigma, numbers were undoubtedly greater. Despite there being little evidence, according to “science” it was thought that deafness was mostly hereditary. It was also a common misconception that deaf couples would almost certainly have deaf children, or if only one party was deaf, deafness would appear in succeeding generations. Influential people such as Alexander Graham Bell argued that deaf people should not marry each other, otherwise a deaf race would be created. Clubs and societies for deaf people were therefore frowned upon in some quarters. Consanguinity was also believed to be another cause with the marriage of cousins. As a consequence, in 1861, it was instructed that those deaf “from birth” should be so described. The confusion surrounding the various causes of deafness is obvious when you read the census reports. For example, it was reported that some mothers attributed the deafness of their child to “fright” or “morbid mental impressions on the part of the mother during gestation”! Undoubtedly, deafness was more common in the past than today but the majority of cases must have been caused by childhood diseases such as scarlet fever, typhus, meningitis, small pox and measles.

A big disadvantage for many deaf people was their lack of education. However, some progress was made here with the setting up of special schools for the deaf. The first school for deaf and dumb children had been set up in Edinburgh in 1760 by Thomas Braidwood, a mathematics teacher, but the first free school was the Asylum for Deaf and Dumb Children of the Poor, set up in Bermondsey in 1792 by the Reverend Townsend. The school moved to Kent Road in 1809 and later to Margate, Kent. By 1861, eleven special schools had been established in England, mainly in major cities, educating around 1000 pupils. Education was seen as a way of “saving” the deaf. It was recognised that these special schools cut deaf children off from the world and severed family and social ties but it was thought that overall, the benefits outweighed these disadvantages. However demand for places always exceeded supply and most of the schools were reliant on charitable contributions. Though the Guardians of the Poor were under a moral, if not legal, obligation to send poor deaf and dumb children to these schools, it is clear that the majority did not have this opportunity. It wasn’t until 1893 that deaf and dumb children were required to be educated.

Of course, many hearing children at this time also did not have the opportunity to read or write but for deaf children, there was the further disadvantage of lack of speech. Deaf children could be taught by the oral method, which was mainly lip reading and articulation of speech, or the manual method, which primarily consisted of hand gestures that formed sign language. In Britain, both methods were often used in the special schools and the deaf were taught to sign by deaf teachers. However, sadly, the teaching of sign language was suppressed in deaf schools after the Milan Conference in 1880. Sign language was seen as detrimental, setting the deaf community apart from the hearing world. As a consequence, the education of deaf children was significantly harmed, with children struggling to understand and learn through tiring lip reading, the allegedly superior method of communication. Hearing parents were only encouraged to speak to their deaf children, rather than communicate using sign language. British Sign Language was not respected or valued as a either a language or a legitimate form of communication until many years later.

When it came to employment, deaf people were thought to be able to support themselves with a variety of occupations, as long as they did not have a job that required frequent direction. However, it was acknowledged that finding the work in the first place could be a problem if you were deaf because of difficulties in communication with prospective employers. Many employers would also be prejudiced against deaf people. In Britain, The Association in the Aid of the Deaf and Dumb was established in 1841 to help deaf people. They put on events such as plays, debates, bazaars, lectures and competitions. They were also instrumental in establishing a church for the deaf in London, St Saviour’s on Oxford Street (it later moved to Acton). There was also the national Deaf and Dumb Society and the British Deaf and Dumb Association, organisations run by deaf people for deaf people. In addition, from the mid-nineteenth century, there were a number of newspapers and journals aimed at the deaf community. It must have been very isolating and lonely at times for a deaf person, deprived of conversation in a hearing world, so societies such as these did a lot to provide a sense of community, where deaf people could meet other deaf people. They also did a lot of fundraising to help deaf people.

Maria Batchelor 1827-1903

As mentioned above, one of my own ancestors, Maria Batchelor, was deaf. She was the younger sister of my great great grandfather, James Batchelor. Many years ago, when I was still a teenager, I was looking at the microfilmed parish registers of St James, Cooling, in Kent. This was the parish that James Batchelor had moved to in 1870, along with his wife, Frances, and their children. Over the years, and with the marriages of their four sons who all produced large families, there was a dynasty of Batchelors recorded in the Cooling registers. Whilst carefully extracting every entry of interest, I came across the burial of Maria Batchelor on December 16 1903, aged 76. Initially, I had no idea who she was but being a contemporary of James Batchelor, I surmised that she might have been an unmarried sister. I was later able to confirm that this was the case and I also discovered that she was deaf. Sadly, there is no evidence of a memorial to her in the churchyard at Cooling, her resting place, made famous by Dickens as the scene where Pip meets the convict, Magwitch, in Great Expectations:

https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/5161075

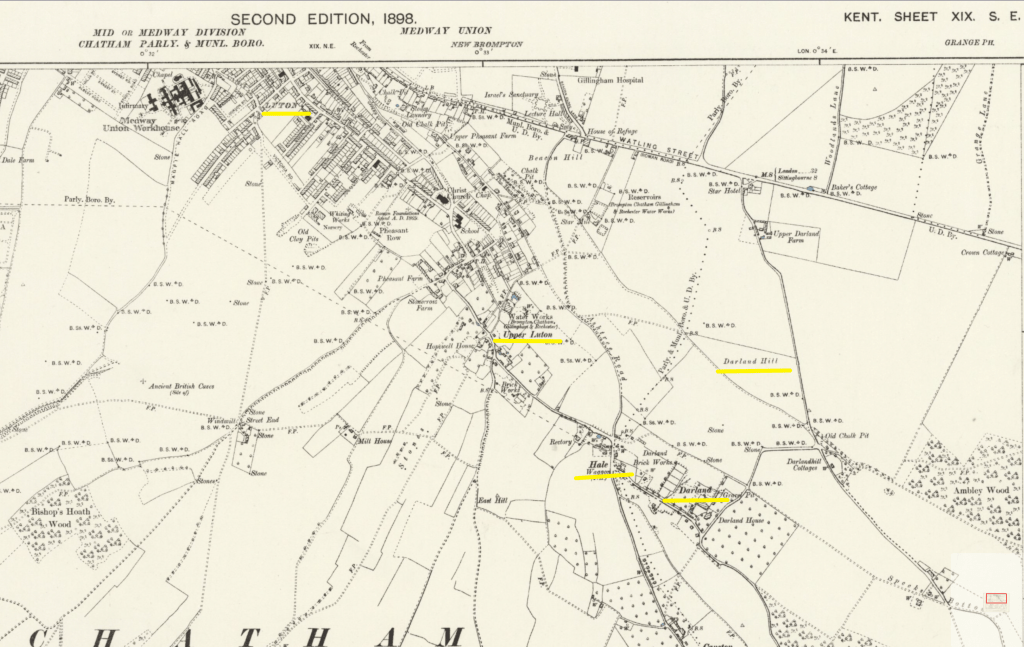

Maria Batchelor was born in Chatham, Kent, ca. 1827 and baptised on May 13th 1827 at the parish church of St Mary’s Chatham. She was the daughter of John Batchelor, a labourer, and his wife, Maria, nee Seers. The family lived in the hamlet of Darland, which is situated on the border between the dockyard town of Chatham and the neighbouring town of Gillingham. Darland, Hale and Upper Luton were situated in an agricultural enclave that today, has largely been swallowed up by the surrounding urban area. However, (as can be seen by the map below), even at the close of the nineteenth century, it was still dotted by many farms:

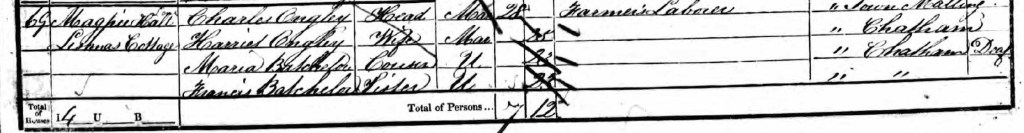

Sadly, Maria was to lose both her parents when she was young, her mother Maria, dying in 1843 and her father, John, in 1847. She can therefore be found living with her married cousin, Harriet Ongley at Listmas Cottage on Magpie Hall Road, close to the Medway Union Workhouse (recorded on the top left corner of the above map) when the 1851 census was taken. The 1851 census was the first census that had a disability column and 23 year old Maria is recorded as being deaf:

via http://www.ancestry.co.uk

As the 1841 census does not record disabilities, it is not known if Maria had been born deaf or had lost her hearing as a child. (The 1911 census is the first census that records the age when a person was afflicted). It is nice to see that after the loss of her parents, she had found a home with her cousin, Harriet. Harriet’s sister, Francis, was also living with them and the three girls were all of a similar age.

Unfortunately, I can find no trace of Maria in the 1861 census. It is likely that she was living in someone else’s house and as such, probably was not enumerated. Perhaps the fact that she was deaf had caused someone to emit her from their census return. However, I catch up with her in the 1871 census:

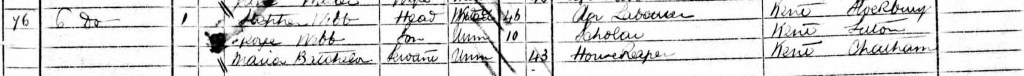

via http://www.ancestry.co.uk

In 1871, Maria is living with Stephen Webb, a widowed agricultural labourer, and his son, George, who was just 10 years of age at 6 Luton Street, Chatham. Maria is a housekeeper to them. In this census, there is no indication that she is deaf. Stephen Webb had been born in Stockbury, the place of birth of Maria’s mother, Maria Seers, so there was a definite possibility that he was a relative. Further investigation revealed that Stephen Webb was Maria’s first cousin, the son of Elizabeth Webb, née Seers, her mother’s sister. No doubt Stephen Webb needed someone to keep house and look after his son after the death of his wife.

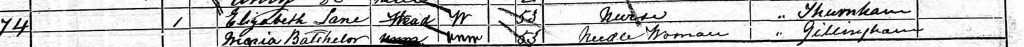

By 1881, Maria had found another job as a needlewoman. She is living with Elizabeth Lane, a widow and nurse, and Elizabeth’s 25 year old son, Henry, who is enumerated on the next page on Kings Road, Chatham:

via http://www.ancestry.co.uk

Elizabeth Lane was the same age as Maria so were they friends who shared lodgings together? I decided to look into Elizabeth’s background and discovered that her maiden name was Elizabeth Webb. She was the sister of Stephen Webb, (who Maria had been living with in 1871) and therefore also a first cousin of Maria. Once again, in this census there is no indication that Maria was deaf.

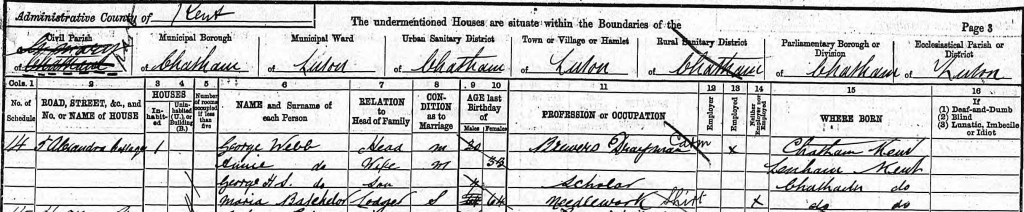

In 1891, Maria was lodging with George Webb, a 20 year old brewer’s drayman, his wife Annie, and their young son George at 5 Alexander Cottage, Luton, Chatham. George senior was the son of Stephen Webb. Maria had acted as his father’s housekeeper twenty years earlier when George had been just a young boy:

via http://www.ancestry.co.uk

Once again, Maria was supporting herself through her needlework. An extra detail added was that she made shirts. In the 1891 census it was also recorded whether someone was an employer, employed or in neither of these categories. It was noted that Maria was not an employer or an employee so this suggests that she made shirts for people on a freelance basis. Once again, there is no indication that she was deaf.

Maria features in census records for the final time in her life in 1901. At this point, she is recorded as living on her own means and the head of her own household at 49 Upper Luton Road in Luton, Chatham. She shares the house with 66 year old Mary Williams, a laundress, and Mary’s 12 year old granddaughter, Harriet. Today 49 Upper Luton Street is a Victorian terraced house that is spread over three floors so perhaps Maria’s rooms were in the basement. This is the only record where she is recorded as Mary. She also states that she is deaf and as an old lady, it is probable that now no stigma would be attached:

via http://www.ancestry.co.uk

From the registers of Cooling, I knew that Maria had been buried on December 16 1903, so I decided to obtain her death certificate, adding to the information that I had on her life:

Maria Batchelor had died from a cerebral haemorrhage at the age of 76 at 57 Albany Road, close to Upper Luton Road where she was living at the time of the 1901 census. She hadn’t moved far. She was described as formerly a church cleaner. Around the corner from Albany Road is the parish church of Christ Church, Luton so this is probably where Maria had her cleaning job:

https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/index.php?curid=102540

The informant on Maria’s death certificate was J. Kitchingham of the same address. A search of the 1901 census revealed his identity, as he was still at 57 Albany Road, Chatham at this date. James Kitchingham was a 39 year old labourer with a shady background. Seeking further information on him, I discovered that he had quite a criminal record for petty theft. In the summer of 1901, he was sentenced to six months hard labour for stealing two shillings. I don’t think he was related to Maria in any way but he was with her when she died and did the decent thing by registering her death.

The impression I get of Maria was that she was a resourceful woman. It is doubtful that she received much education, or had the opportunity to attend a special school, but she worked hard to be independent through a variety of jobs. She was obviously skilled at needlework but had also worked as a housekeeper and a church cleaner. Like many deaf people, she never married so she had to support herself. There is no indication that she was the recipient of charity, despite the limitations imposed on her by her deafness. Luckily, it appears that she had supportive relatives, particularly her Webb cousins on her mother’s side of the family. My research into her life certainly illustrates that it is always worth investigating the people who your ancestors were living with, even if at first, they don’t seem to be family members. It is interesting to note that her deafness was only recorded in two censuses, once in 1851 and once in 1901. Did her cousins feel it was an intrusive question? My own ancestor, James, and his family, obviously cared for her and arranged for her to be buried close to where they lived in the churchyard of Cooling. I’d like to think that she was frequently invited to stay with her family in Cooling. At the time of her death, her brother, James, was the only one of her siblings still alive so he was her closest relative.

One’s research into the lives of ancestors can sometimes seem inadequate, particularly when you can only track their movements every ten years through the census records. Sadly, Maria is missing from the 1861 census so I have no knowledge of her life as a young adult. However, she seems to have spent all her life close to where she was born in the Luton area of Chatham. I hope she found some deaf friends in the town and could communicate with them by signing. Perhaps there was an association or society for deaf people in Chatham, which laid on special events for deaf people.

I have a rather lovely postscript to the life of Maria. As I said earlier on in this piece, I first discovered the existence of Maria when I was a teenager and found her burial in the parish registers of Cooling. Around this time, I did meet some distant cousins and we were discussing the family history. I happened to mention that I had found a reference to a Maria Batchelor, who must have been a relative. They retorted that yes, they had heard of Maria Batchelor, as they had in their possession a sampler that she had made. Her name, Maria Batchelor, was embroidered on the piece and they had always wondered about her identity. Since then, my research has revealed that she was a skilled needlewoman. She had probably created this sampler as as gift for her brother, or for one of her nephews and nieces in Cooling. Her name and work lives on.

© Judith Batchelor 2021

For further information on blind people in Victorian England please read Ancestors who were Blind

That was such an interesting read. It is sad when you can’t find any reference for a certain period of life. Maria sounds a very strong woman and great needleworker. This is a memorable tribute to her

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I enjoy shining a light on a person who seems to have led a rather obscure life. It was really interesting to find out about the social attitudes to deaf people at the time. Luckily, Maria appears to have enjoyed close family ties.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing Maria’s story. How much harder her life would have been at a time when life already had plenty of challenges.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, that is what I concluded too. I really admire her.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a beautiful read! You did an outstanding job researching and presenting her life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your lovely compliment! ☺️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting read. And I agree, Maria was very resourceful. I’m sure many in her circumstances ended up in the Workhouse. Having the support of her family must have meant a lot. I love that relatives still have one of her samplers. Such a lovely keepsake.

Two of my third great-aunts and their younger brother were all deaf. Again, because of the lack of that columns in the 1841 Census, I do not know if the older of the women was deaf from birth, or because of something like scarlet fever. Certainly in 1851, Sarah (age 9, recorded at the Asylum) and Alfred (age 7 – at home) were deaf.

Both Jane and Sarah attended the school on Kent Road and I believe Alfred did as well. Jane died in 1845, so I don’t know if she had an occupation, but Sarah was a seamstress and Alfred a tailor (which is why I believe he too went to the school), as per their census entries. Though born in east Kent, the latter two followed their older siblings to London.

Sarah married a deaf man who was a painter on glass, so it seems the deaf community, at least in London, found each other. It’s also possible she had known him from school. Their two daughters were also deaf. Interestingly enough, if it was genetic, it hasn’t, so far, resurfaced in other descendants from that line.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing your stories of deaf relatives. I have read about the school on Kent Road so it is very interesting to hear that your relatives attended. From what I have learnt, one of the advantages of specialist schools is that they often form tight-knit and supportive communities. It must have been marvellous for deaf children to meet other deaf children and feel less isolated. I wonder whether Sarah had first met her husband at school?

LikeLike

Thank you for another interesting and moving story. It was so nice to read from all the research you have done that Maria had support from family. It is amazing that one of her samplers has survived and stayed in the family.

Your blog inspired me to go back to look further into my husband’s great-grandfather’s life. In the Census 1871, William Thomas, born about 1813 in Bristol, was deaf from a kick by a horse as a child. I know very little about him other than he lived in Bristol working as a currier, married and had eight children. I have to do all my research online from Australia but I am going to see if I can find any more information.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s wonderful, I do hope you are able to find some more information on William Thomas.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for writing this blog post and providing resources for researching deaf ancestors in the United Kingdom. In 2015, I wrote a blog series about the three deaf siblings of my 3rd-great-grandmother and historical records in the United States that can be used to research deaf ancestors here. In 2016, my first grandchild was born deaf and in 2019 his sister (also deaf) was born. Each received cochlear implants around one year of age. We now know our hearing loss (my two children and I are all hard of hearing at some level) is caused by genetics and not multiple ear infections we all experienced as children. It’s entirely possible that deaf gene (Connexion 26) came down my Dickinson line through the generations to my daughter.

I will be adding a link to your blog post to the last post in my series so that others who are researching deaf ancestors in the UK can find it. I’ll also be searching the records groups you listed, as my son-in-law’s family has lines that came over from England fairly recently. Perhaps we can find some information as to the genetic source of deafness in his lines.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Miriam, it was great to hear from you and learn more about your deaf ancestors. It’s wonderful that modern science has been able to identify the gene passed down in your family and cochlear implants have helped your grandchildren. It must have been very hard for deaf people in the past who had little medical help, few opportunities for education and frequent societal prejudice. Your message got put in my spam folder so apologies for not replying sooner. Jude

LikeLike

How lovely that Maria’s sampler has been handed down. I was very interested (and saddened) to learn that sign language was repressed for a time. Through my day job I recently heard about someone who had a deaf ancestor, and they were grateful for a link to this article. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, glad that my article was of interest. I found it rather shocking that sign language was suppressed for so long, and similarly, so was Braille. There was this sense that hearing/seeing people would be excluded with these developments. Of course, they weren’t the needy ones. The effect was to exclude those that couldn’t hear or see, who had little say in these decisions.

LikeLike