Although many of our ancestors had the same job for the whole of their lives, others pursued a variety of occupations. Through looking at census returns, we can often plot their changing roles, as well as their travel to different places. Often, I think these individuals must have been go-getters, driven to try new things and improve themselves. Circumstances might have also necessitated a change in direction for some, especially if there was a downturn in the industry in which they were employed. They had to move away from where they had roots, perhaps to a town to find better opportunities. One career open to ambitious young men, even those from a humble background, was the police. My great great grandfather, Thomas Maton, served for a time with Hampshire Constabulary and I wanted to find out more about his career.

Thomas Maton was born in 1841 in the village of Amport, near Andover, Hampshire. His father, Richard, an agricultural labourer, had died when he was still a teenager and when the 1861 census was taken, Thomas was working as a shepherd and his younger brother, Edward, was a plough boy. Both boys had to support their widowed mother, Elizabeth, who was taking in laundry to make ends meet. Maybe looking after sheep was a rather boring and lonely job for a young man, spending hours all alone on the hills above Amport. That job clearly didn’t last too long for when Thomas married his eighteen year old sweetheart, Sarah Ann Dicks, across the county border in her home village of Newton Tony, Wiltshire, on August 16th 1862, he was working as a gardener. The couple settled in Amport and it was here that my great grandmother, Elizabeth Jane Maton was born a few months later, just before Christmas. However, by the time the 1871 census was taken, Thomas had taken his wife and young children to Mottisfont, Hampshire, to the south of the county, and was working there as a police constable:

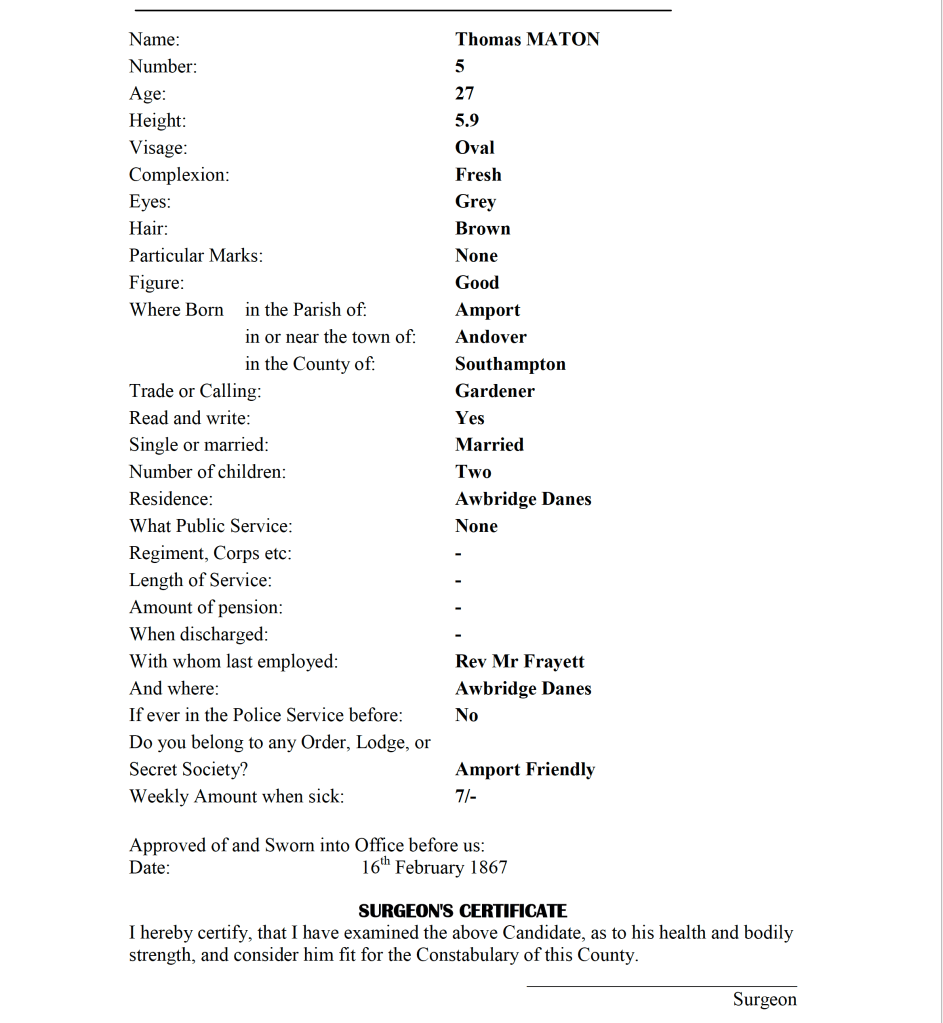

I knew very little about Thomas’ career in the police but whilst having a “Google” one day, I came across the Hampshire Constabulary History Society. I decided to contact the curator and to my delight, he soon responded, and provided me with a transcribed record of Thomas’ examination. As part of the application process to join Hampshire Constabulary, Thomas had to undergo an examination to assess his suitability and after being questioned, his answers were duly noted on the form:

OF A CANDIDATE FOR THE SITUATION OF A POLICE CONSTABLE

Hampshire Constabulary Examination Books 1840-1967 ref 200M86

Thomas Maton stated that he was 27 years old, married with two children and had been born in Amport, near Andover. He was a member of Amport Friendly Society, which provided insurance in case he was sick, specifically 7 shillings a week. Since I have no photograph of Thomas, it was wonderful that the form provided a physical description of him. From this, I learnt that Thomas was 5 foot 9 inches in height, had an oval visage, a fresh complexion, grey eyes and brown hair. He had no particular marks and his “Figure” was described as “Good”. Given the demands of the job, it was important that police officers were strong and healthy and the surgeon testified that he considered Thomas “fit for the Constabulary of this County”. The examination had taken place on February 16th 1867 and Thomas was given the number 5. He was to be stationed at Romsey, a historic market town that until 1865, had had its own borough police force. At this date it was merged with Hampshire Constabulary, so Thomas was probably the fifth constable to be recruited from this time.

From his examination, it can be seen that Thomas had moved away from his home village of Amport and originally, had taken his family to Awbridge Danes, a rural hamlet close to Mottisfont, Hampshire to the south of the county. The village is dominated by Mottisfont Abbey, now a National Trust property, and the Mottisfont Estate. He had found work as a gardener for the Reverend Mr Frayett, who was named as his former employer (and presumably vouched for Thomas’ character). Frayett didn’t seem to be a surname so I suspected that the name has been incorrectly transcribed. However, I found the Reverend Paulett St John living at Mottisfont Rectory when the 1871 census was taken and reckon that it is him!

After some time working for the Reverend Paulett St John, Thomas decided to give up gardening as as career, and applied to join Hampshire Constabulary, as a police constable. Applicants to the police force came from a wide range of backgrounds but men were selected on the basis of their good character, intelligence, sobriety, physical strength and height. Many forces stipulated that applicants had to be at least 5 foot 10 inches (178 cm) in height. Thomas was 5 foot 9 inches so just shy of this benchmark but on the tall side. It was also necessary to be able to read and write well. The authorities were looking for candidates who were honest, obedient and willing to be devoted to their duties.

Although parish constables had long had a role in keeping the peace, sometimes assisted by night watchman in cities, the first professional police force was set up by Sir Robert Peel’s Metropolitan Police Act in 1829, which formed the Metropolitan Police force in Greater London. This was followed by the London City Police in 1832 (renamed the City of London Police) and soon afterwards, other cities followed suite with the passing of the Municipal Corporations Act in 1835. The Rural Constabulary Act of 1839 then allowed county areas to establish police forces. However, it only became compulsory for cities and counties to have a police force after the passing of the County and Borough Act in 1856, which provided central government funding. Hampshire Constabulary was formed in 1839, with its headquarters in Winchester, where the county gaol was situated. According to Hampshire Constabulary History Society, when the Constabulary was formed, there were 106 officers with 1 Chief Constable, 14 superintendents and 91 constables. This gave a ratio of one officer to every 1,200 inhabitants or 4,000 acres. When Thomas joined in 1867, there were 260 officers in the Constabulary, so the manpower had more than doubled.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Police_helmet_badge_Hampshire_Police.jpg

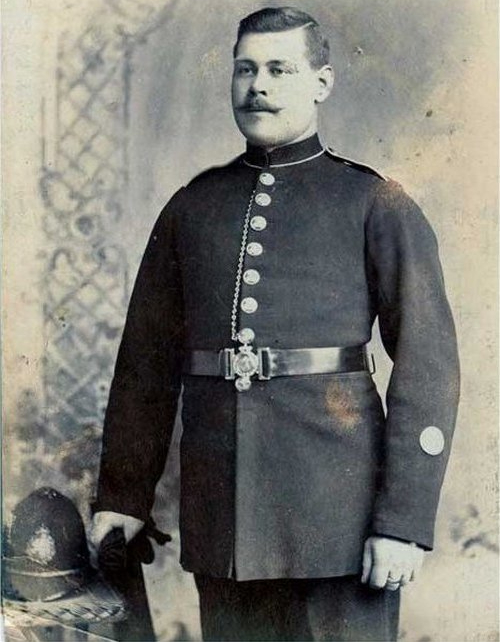

In order to make a clear distinction between police constables and soldiers, the uniform of policeman deliberately looked very different. It was dark blue in colour with shiny brass buttons and a belt clasp which displayed the constabulary’s badge. It had to kept smart and clean at all times, as an immaculate turnout reflected pride in the job. It also had to be worn at all times in public, even when off-duty, (which must have cramped one’s social life!) No weapons were carried by constables even though the threat of violence was never far off. A police helmet offered some protection from assault and a truncheon could be used. Handcuffs were carried to detain suspects.

Constables would be given a specific “beat” to patrol, which could cover a large area in rural areas. When on duty, a constable had to be at a particular point at a set time before moving on shortly afterwards. Even when off-duty, they were expected to be ready for work at short notice. It was their business to know where local troublemakers lived and to keep a close watch on places that could be targeted, acting as a visible deterrent to those who might be tempted to break the law. New recruits were issued with a rule book which laid out their legal powers and gave guidance on how they should handle different situations. It couldn’t have been an easy job, out in all weathers, covering great distances on foot. The hours were long too with seven days a week on duty and only five days off a year. It wasn’t until 1890 that a weekly rest day was given. Discipline was strict and there were many personal restrictions. For example, drinking with a friend in a pub was frowned upon, even when off-duty. Similarly, a constable could only get married with the permission of his superiors. Unsurprisingly, there was a high drop out rate amongst new recruits.

Nevertheless, there were some attractions to joining the police. When Hampshire Constabulary was formed in 1839, the pay of 18 shillings a week was double that of an agricultural labourer. No doubt the uniform also commanded respect and deference from certain quarters and you were in a position of real authority. It also offered a proper career with potential for advancement and promotion and a steady and regular income. After you had seen service of twenty five years, it was possible that you could be awarded a pension, (though this was discretionary until 1890). Apprehending criminals must have been exciting at times and there was the opportunity of performing public service. Whatever his motivation, it must have been a job that appealed to Thomas Maton.

To find out what Thomas got up to in the course of his duties, I turned to contemporary newspapers. Obviously many incidents in his career went unreported but the evidence here does give a flavour of his police work. One of the most distressing events in his career must have been when Thomas had to retrieve a dead body from a river. The Hampshire Telegraph, dated Saturday 20 March 1869, reported that the body of Esau Welstead, a 27 year old railway gatekeeper, who had been missing for a month, had been found in the River Test, a short distance from the mansion at Broadlands on the edge of Romsey. It had been spotted by a stableman in the employ of Lady Palmerston who contacted the police. It was reported that P.C. Maton got into a boat and when he reached the spot, he hauled the deceased out of the water. Apparently the dead man had been drinking the night before he went missing and it was believed that he had fallen into the river. The coroner’s jury returned an open verdict of “Found drowned”.

By Anthony de Sigley – Own work, Public Domain

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34026185

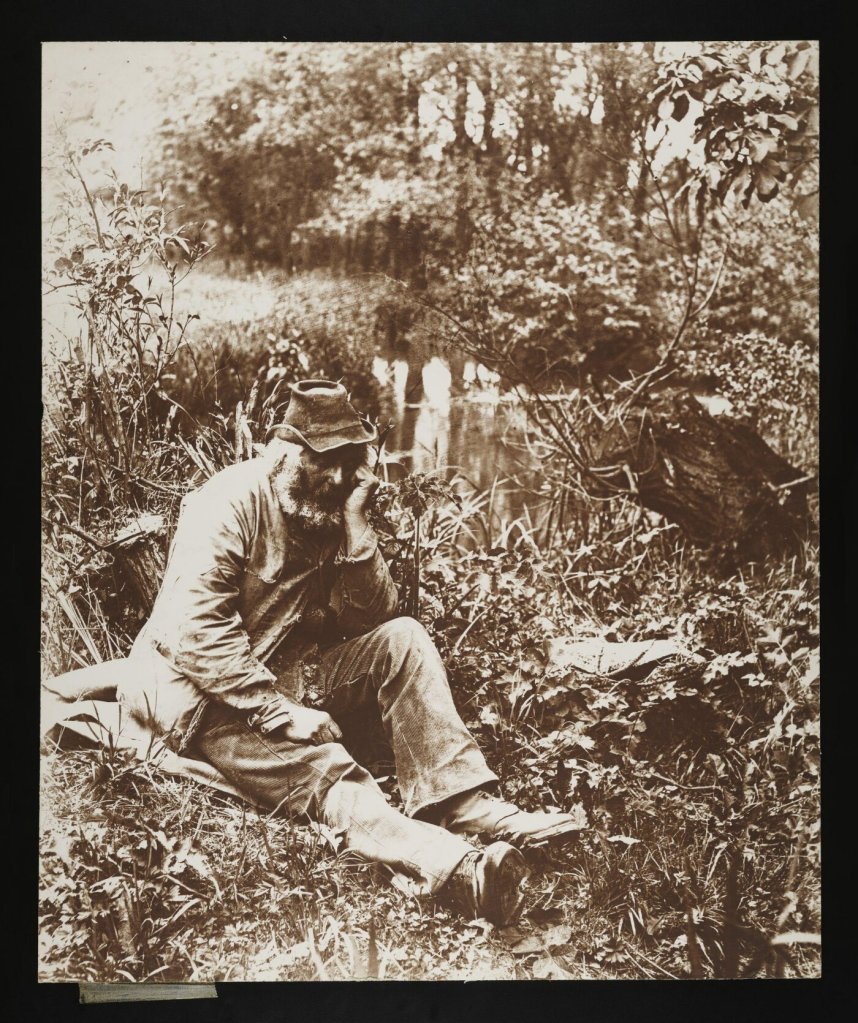

Later in 1869, a report appeared in the Hampshire Advertiser on Wednesday 10 November 1869 about a travelling clock mender who had been charged under the Vagrant Act with wandering about and having no visible means of subsistence. At this time, vagrancy was a way of life for many in rural areas. Work was sought and if there was none, the vagrant tramped on to a new place. However, it was against the law because it was widely believed that all vagrants became thieves in the end. Police Superintendent Cook had been returning from Lymington to Lyndhurst with Police Sergeant Gibbs and Police Constable Maton overnight. It was 2 o’clock in the morning and they were passing Clayhill when they saw a man lying down in the fern. P.C. Maton got out of the cart and took him into custody:

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1463356/old-surray-tramp-photograph-martin-paul/

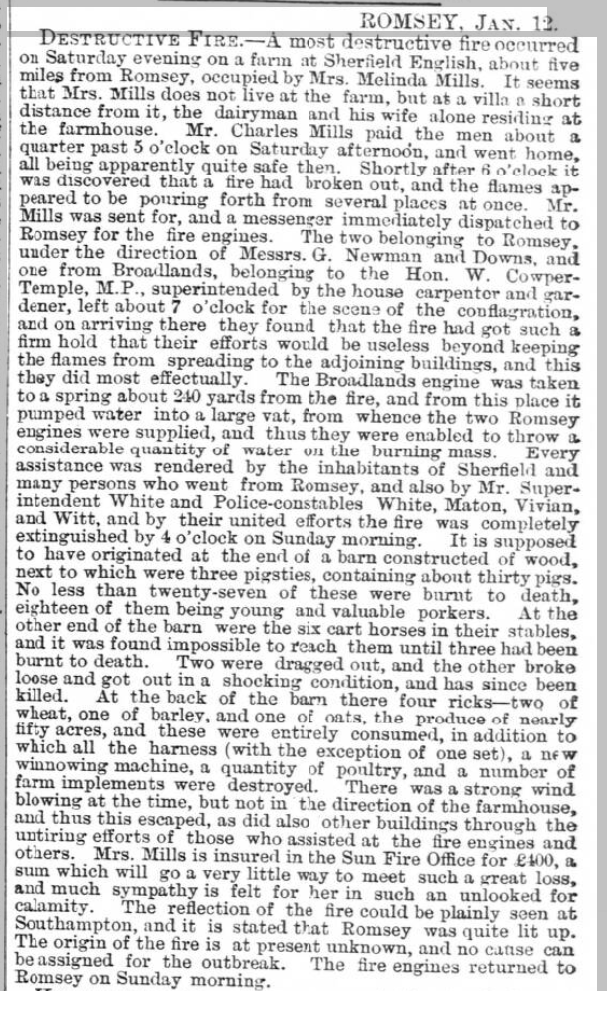

The police also had a role in assisting the fire brigade. A report in the Hampshire Advertiser dated Wednesday 12 January 1870 gave details of a destructive fire at a farm at Sherfield English, about five miles west of Romsey, that had broken out about 6 o’clock on the previous Saturday evening. Fire engines were called to try to stop the fire from spreading and a great effort was made to get the fire under control. Superintendent White and Police Constables White, Maton, Vivian and Witt joined to give assistance and by 4 o’clock on Sunday morning, the fire was completely extinguished. Twenty seven pigs, three cart horses, four ricks – two of wheat, one of barley and one of oats – and the produce of nearly 50 acres was consumed along with the harness, a new winnowing machine, a quantity of poultry and a number of farm implements. No doubt P.C. Maton and his colleagues earned the gratitude of the villagers of Sherfield English, as they heroically helped to put out the fire, staying up all night assisting the fire brigade:

via http://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

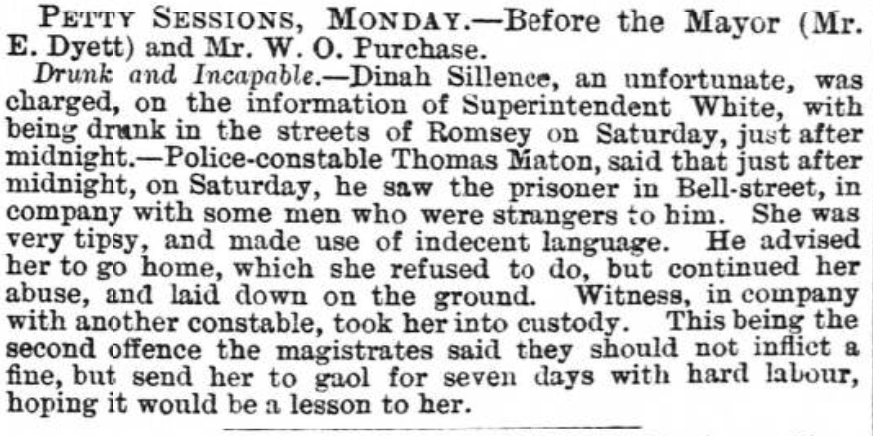

At the Petty Sessions on Monday 29 August 1870, Dinah Sillence, “an unfortunate” was charged with being drunk on the streets of Romsey on Saturday, just after midnight. It was reported in the Hampshire Advertiser that Police Constable Maton had seen the prisoner in Bell Street, in the company of some men who were strangers to him. She was very tipsy, and made use of indecent language. He advised her to go home, which she refused to do, but continued her abuse, and laid down on the ground. Being verbally abused, late at night on the streets of Romsey, must have been an unpleasant and probably not an uncommon experience for P.C. Maton:

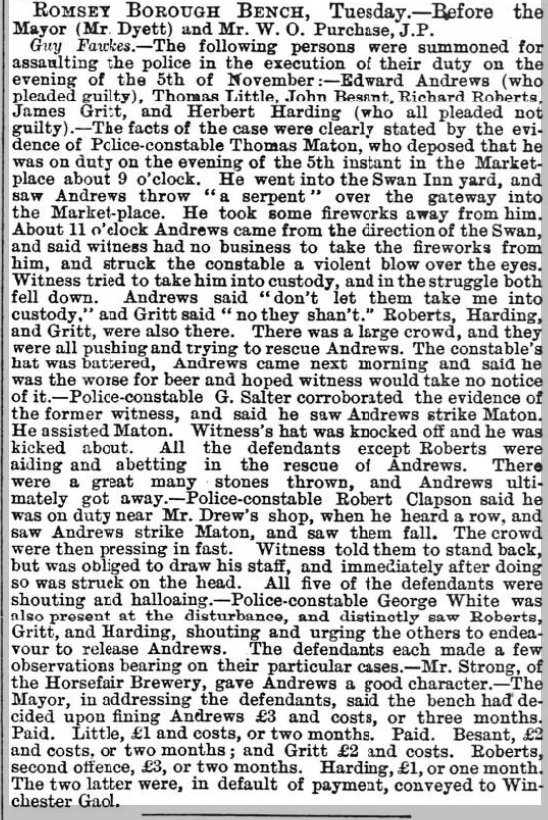

Romsey had expanded as a brewing town in the mid-19th century, and was known for its extraordinary number of pubs, which were often the scene of public disorder. A Guy Fawkes night street brawl, which resulted in P.C. Maton being violently assaulted was reported in the Hampshire Advertiser on Wednesday 16 November 1870. Police Constable Maton appeared as a witness at Romsey Borough Bench, where he gave his evidence. He had been on duty and was in the Market Place in the centre of Romsey at 9 o’clock. He went into the yard of the Swan Inn and saw a man named Edward Andrews throw “a serpent” over the gateway into the Market Place so he took some fireworks away from him. About 11 o’clock, Andrews came from the direction of the Swan and said that the witness (Maton) had no business taking the fireworks from him. He struck the constable a violent blow over the eyes. Men named Roberts, Harding, and Gritt were also present. P.C. Maton tried to take Andrews into custody and in the struggle, they both fell down. Andrews said “don’t let them take me into custody” and Gritt said “No they shan’t.” There was a large crowd, and they were all pushing and trying to rescue Andrews. P.C. Maton’s hat was battered in the brawl. They obviously thought that P.C. Maton was spoiling their fun and it must have been very frightening for him:

Picture Chris Levy

https://www.closedpubs.co.uk/hampshire/romsey_swan.html

P.C. Maton was also involved in a violent encounter with night poachers on the Mottisfont Estate, as reported in The Hampshire Advertiser on Saturday 23 November 1872. Poaching had long been a rural crime but the growth of the railways and the canal system meant that it was increasingly becoming a crime committed by organised violent gangs, rather than a few local men looking for a rabbit or game for the cooking pot. The head keeper to Lady Barker Mill of Mottisfont Abbey, Edward Flatman, received a call from P.C. Maton, early in the morning on November 14th 1872, a little before 1 a.m. P.C. Maton, now working at Mottisfont, had been on duty near Dunbridge Station, when he heard guns firing in the direction of Drove Copse. They went out together to intercept the poachers and this is Flatman’s testimony:

Whilst talking to him [Maton] I heard the report of a gun in the direction of Drove-copse, and whilst preparing to go with him I heard another report in the same direction. I then called to my assistance two of the woodman’s sons named Samuel and Frederick Rogers. I directed them to go to “Doling’s-arch”, which is an accommodation road for the farmers across the railway, and which is situate near Drove copse. We waited there concealed for some twenty minutes, during which we heard the report of two more guns. Shortly afterwards I saw four men coming towards the arch where we were, apparently from the direction of the cover. There are a great many pheasants there, and it is strictly preserved. …When they got near us we made a rush at them, and the man Newell, who is now at large, threw two stones at me. I went after him, and just before catching him I hit him over the head with my stick. We then struggled with him, and he hit me severely on the arm with a stone he had in his hand, and which I produce. He also bit my thumb and kicked me. We both went down together, and he ultimately got away from me.

The Hampshire Advertiser, Saturday 23 November 1872

via http://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

Although Newell got away, the other three poachers were captured, Doling at the scene, who was handed over to the custody of P.C. Maton, whilst the other two, Austin and Terry, were arrested the next day.

The newspapers certainly give an idea of the eventful life of a police constable in Hampshire Constabulary. It is evident that P.C. Maton would have had a lot of responsibility, taking individuals into custody at the police station and on occasion, testifying as a witness in court, sometimes even travelling into Winchester. For example, two men were brought into custody by P.C. Maton and his colleague P.C. Lovelock and fined at the County Petty Sessions for fighting at Romsey Fair. A carter was convicted of riding without reins and therefore driving dangerously on the evidence of P.C. Maton. Two men who refused to leave the premises of a pub at Easton were fined at Winchester County Bench, the charge brought by P.C. Maton. P.C. Maton was also brought as a witness when a fifteen year old boy, Alfred Grant, was charged with stealing trusses of hay and bringing them to the stables of his father, who was a carrier. Alfred was crying so P.C. Maton said to him “This will teach you to let people’s hay alone!” though in the end, Alfred escaped punishment.

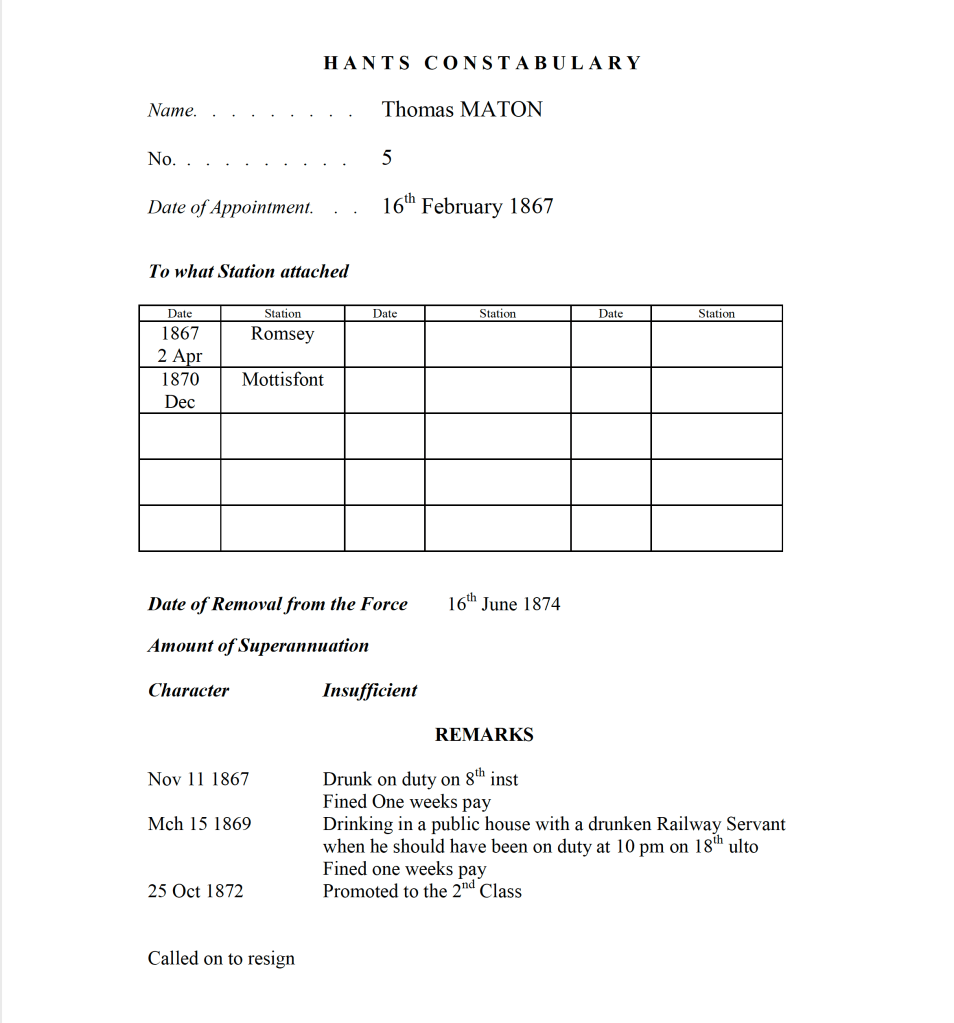

The examination form of Thomas Maton also gives some further detail on his appointments. He was first attached to the police station at Romsey from April 2 1867, perhaps after having undergone some training for the preceding two months. He remained there until he was removed to the station at nearby Mottisfont in December 1870. However, it was a shock to discover that on June 16th 1874, Thomas Maton was forced to resign from Hampshire Constabulary. The reason given was “Insufficient character”:

OF A CANDIDATE FOR THE SITUATION OF A POLICE CONSTABLE

Hampshire Constabulary Examination Books 1840-1967 ref 200M86

Earlier on in his career, it is clear that Thomas had fallen foul of the strict rules that governed police officers, being fined one week’s pay on two separate occasions. In his first year of service, he had been caught being drunk on duty and in the Spring of 1869, he had been found drinking in the pub with a drunk employee of the railway, when he should have been on duty. Interestingly, when looking at the newspaper reports, it is clear that this incident happened the day after he had retrieved the body from the river on the Broadlands Estate. You can imagine how this would have shaken him. Perhaps Thomas was telling a colleague of the deceased what had happened. However, he subsequently had a clean bill of service and was promoted to a 2nd Class Constable in October 1872. Given this promotion, only eighteen months previously, and his obvious bravery and diligence, as recorded in the newspaper reports, it seems rather surprising that he was forced to resign in June 1874. He had had no misdemeanours against his name for the past two years. Perhaps he had fallen foul of a hostile new superior or something had happened that meant he was forced to leave quickly. This was a big blow for a married man who by then, had six young children to support. He would have been forced to return the uniform that he had worn so proudly for the past seven years.

Judging from an earlier orders book, kept by Hampshire Constabulary and viewed on the website of the Hampshire Constabulary History Society, those who had committed serious offences, (insubordination, disobedience, often allied with drunkenness), were instantly dismissed without pay. Those who were called on to resign were deemed unsuitable or lacking the right qualities to be a policeman or were guilty of being negligent in their duties. Whatever the circumstances, Thomas found himself in need of a new career and with his growing family, moved to Salisbury where he took a job as a railway signalman. Later in his old age, he became a milkman!

Looking at Thomas Maton’s job as a police constable, I feel admiration. He obviously found himself in difficult situations that required bravery, a cool head and diplomacy. Not everyone in the local community would have been supportive of him and have appreciated his role in keeping law and order. Some people would be distrustful and think that he was a spy, or there to inform on them, so making friends would have been difficult. Taking into custody popular characters would drag your name into the mud. The poor were often those who poached or committed larceny so as a policeman, you would be viewed to be on the side of the rich, not the ordinary working man or woman who was struggling to make ends meet. There was always the potential for a clash of loyalties in your relationships with the public, your colleagues and even your own family. However, judging by the newspaper reports and his promotion to a 2nd Class Police Constable, Thomas Maton was doing well until his career was brought to an end in June 1874. I would love to find out what was the real reason behind this decision.

Newspapers have certainly been a valuable source for information on Thomas Maton’s police career and his examination form has given me some wonderful information on him. Since the examination form has been transcribed, I would love to get a copy of the original record, which is held by Hampshire Record Office. A useful source for information on the surviving records of each police force is the book, “My Ancestor was a Policeman”. For Hampshire Constabulary, there are general orders, constables’ reports, personnel records, licensing records, station reports and messages book for the period 1840-1967, all held by Hampshire Record Office. I am planning on investigating these to find out more about Thomas Maton’s career with the Hampshire Constabulary.

© Judith Batchelor 2022

Resources

Victorian Policing – Gaynor Haliday, Pen and Sword History, 2007

The Victorian Policemen – Simon Dell, Shire Library 2004

My Ancestor was a Policeman: How can I find out more about him? – Anthony Shearman Society of Genealogists (2000)

British Police History – https://british-police-history.uk/cgi-bin/index.cgi

Hampshire Constabulary History Society – https://british-police-history.uk/cgi-bin/index.cgi

Knowing little about police constables, I was fascinating by your research and findings! TY so much for sharing background about your g-g-grandfather.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really enjoyed reading about Thomas Maton’s experiences as a PC and it was interesting to read your thoughts on the pros and cons of the career. After his bravery and determination, it’s such a shame that he was dismissed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I couldn’t help feel rather sorry for him. There must be more to the story!

LikeLike

What a story…and yes, given he’d been promoted, one does wonder what led to his being called on to resign. Maybe something new will come to light at some point.

My great-grandmother’s two sisters both married policemen, though only one remained on the job through to retirement. They both served in London.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I believe the Met Police has some excellent records. You could try contacting their heritage team: https://www.met.police.uk/police-forces/metropolitan-police/areas/about-us/about-the-met/met-museums-archives/

LikeLike

Thoroughly enjoyed your wonderful post! My 3x great-grandfather William Spring was a police constable in Gloucestershire around the 1850s. Like you describe, it was an incredibly challenging job. Over the course of 5 years, newspapers reported that William was assaulted at least 9 times while on duty – no doubt, there were many other times as well.

I found an 1830 Gloucestershire recruitment advertisement for police officers that warned “you must expect a hostile reception from all sections of the public and be prepared to be assaulted, stoned or stabbed in the course of your duties.” Hard to believe anyone applied for the job!

The advertisement also revealed another use for their top hat: “No meal breaks are allowed. The top hat may be used to hold a snack.” (https://gloucestershirepolicearchives.org.uk/content/from-strikes-to-vips/changing-laws/advertisment-for-police-officers-peelers-1830)

Interestingly, my William lasted about 6 years as a constable and then, like your Thomas, he moved away and took a job as a railway guard. He led a colourful life, later ending up as Mayor of Swansea. Thanks again for a fantastic article!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Poor William! It’s not surprising that there was such a high drop out rate, given the violence policeman experienced. Amazing that William landed up being the Mayor of Swansea. He must have been an exceptional person.

Thank you so much for sharing the advertisement. Now we know where Paddington got the idea of keeping his marmalade sandwiches in his hat!

LikeLike

What a great quote! It sounds as if they had the sympathy of the magistrate.

LikeLike

This is a great piece of social history and the clips from the local papers complete with archaic descriptions really bring it alive. It is fascinating to get a glimpse of what Thomas life was like and the context on which he lived. Thank you !

LikeLiked by 1 person

It sounds like it was a really tough job. I admire Thomas!

LikeLike

Thanks Jude for sharing this wonderfully detailed story about your great-grandfather and Police Constable Maton. This is an excellent glimpse into the life of a Village PC and I am surprised to read about the levels of violence that were going on at the time! We will never know the reasons he was forced to leave, but he clearly showed his diligence and integrity in his years of service prior to this. Thanks for sharing this Jude

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am hoping to one day find more clues in the records of Hampshire Constabulary, held at Hampshire Record Office. It will always bug me otherwise, as something must have happened to cause his resignation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There will be a reason but that’s the frustrating part of family history we don’t always get to know what the answer is

LikeLiked by 1 person