Tracing ancestors in London in the 18th century can be hugely daunting. The parish registers are large and it can be difficult to identify your ancestor amongst all the other candidates in the vicinity who share the same name. In addition, many of our ancestors would have arrived in London from elsewhere, attracted by the opportunities that the big city afforded but there are no helpful census records to reveal where they were born. That said, there are some rich record sources that can be utilised when tracing London ancestors, particularly if they had a skilled occupation.

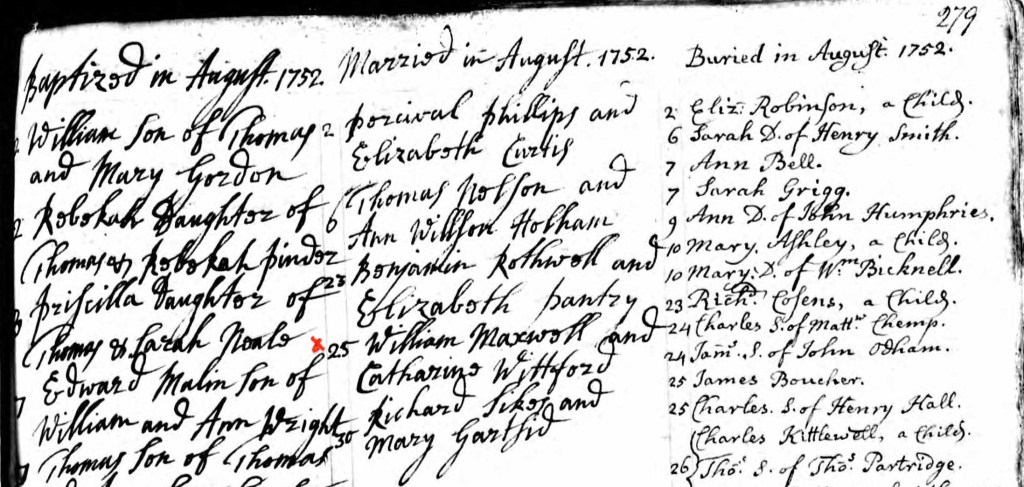

Catherine Whit(t)ford and William Maxwell were wed on 25th August 1752 in the parish church of St Mary, Newington, Surrey. As the wedding took place just before the passing of Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act the following year, the entry is characteristically brief and only their names are given in the composite register:

via https://www.ancestry.co.uk

London, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538-1812

Newington, situated on the south bank of the River Thames, was largely a farming community for the first half of the 18th century but after their marriage, William and Catherine must have seen the area dramatically change with the construction of Westminster Bridge in 1750 and improvements to London Bridge, which attracted development to the area. Since William was a waterman, who ferried passengers in his boat across the Thames, the increased traffic must have been beneficial. Between 1757 and 1765, William and Catherine had six children baptised in the neighbouring parish of St John Horsleydown, Southwark:

- Ann bpt 9 January 1757 (b 19 Oct 1756)

- Elizabeth bpt 28 Oct 1758

- William bpt 7 Jan 1759 (b 14 Dec 1758)

- John bpt 11 Dec 1760 (b 11 Dec 1760)

- Amy bpt 5 Sep 1762 (b 19 Aug 1762)

- Catherine bpt 4 Nov 1765 (b 16 Oct 1765)

John Buckler (1770-1851), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

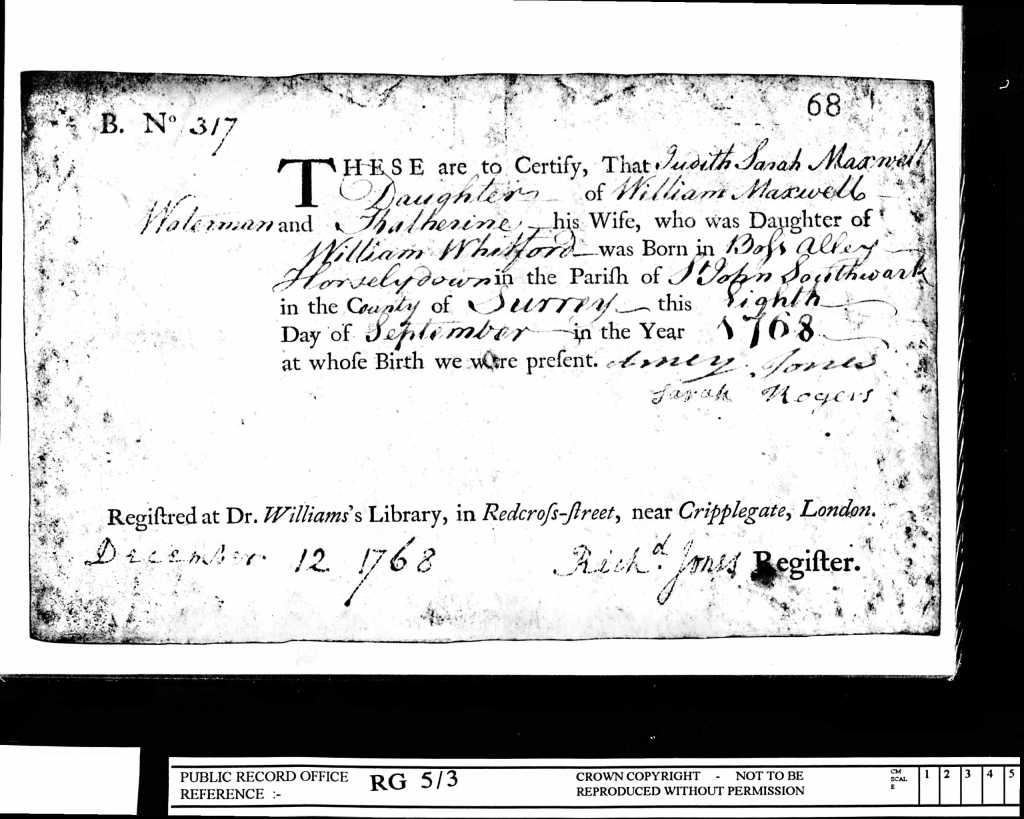

One further child, Judith Sarah Maxwell, was born to William and Catherine but after her birth, her parents did not get her baptised in their local parish church. Instead, they registered her birth at Dr Williams’s Library:

National Archives (U.K.)

England & Wales, Non-Conformist and Non-Parochial Registers, 1567-1970

via https://www.ancestry.co.uk

The General Register of Births of Children of Protestant Dissenters was set up at Dr Williams’s Library in 1742, as a means of providing evidence of a birth in the absence of a baptism. When the Register was closed in 1837, nearly 50,000 births had been registered. Parents paid a small fee to record the name and date of birth of their child. The parents had to bring a certificate from the local incumbent, a midwife or from witnesses who could verify that the child had indeed been born. After the birth had been recorded in the register, the certificate was filed and a copy was returned to the parents, endorsed with a notation that the birth had been registered. The certificates are held by the National Archives in the collection, RG5.

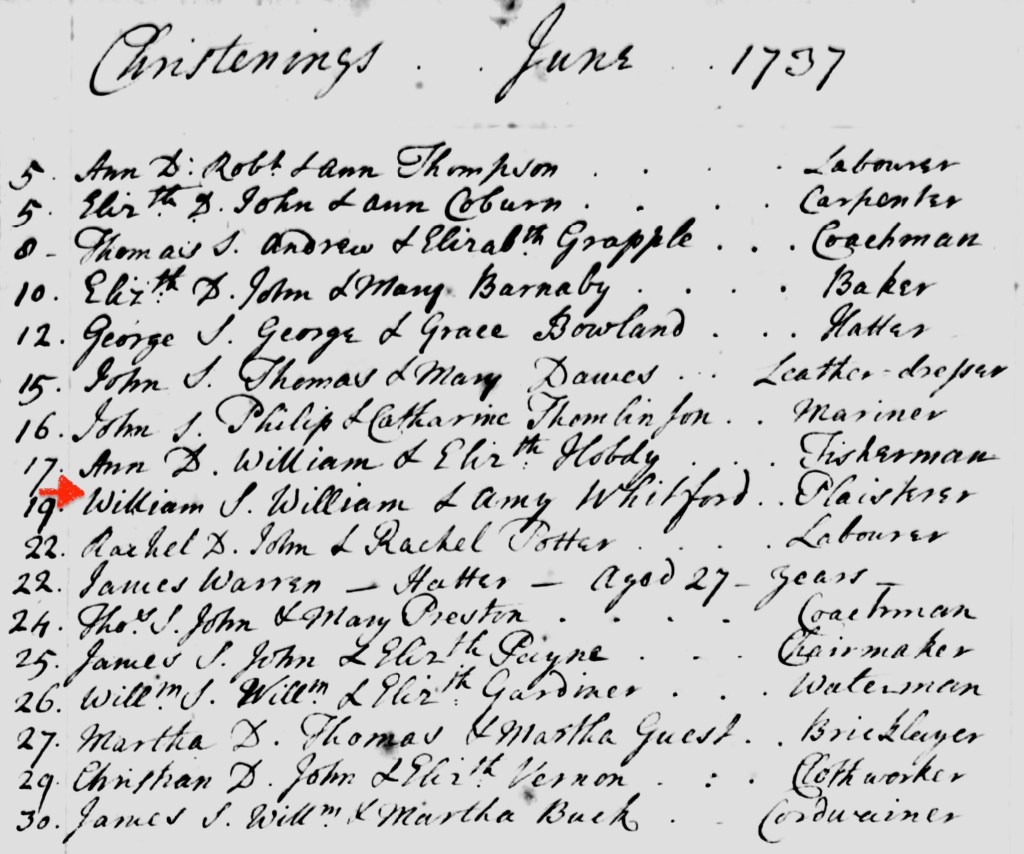

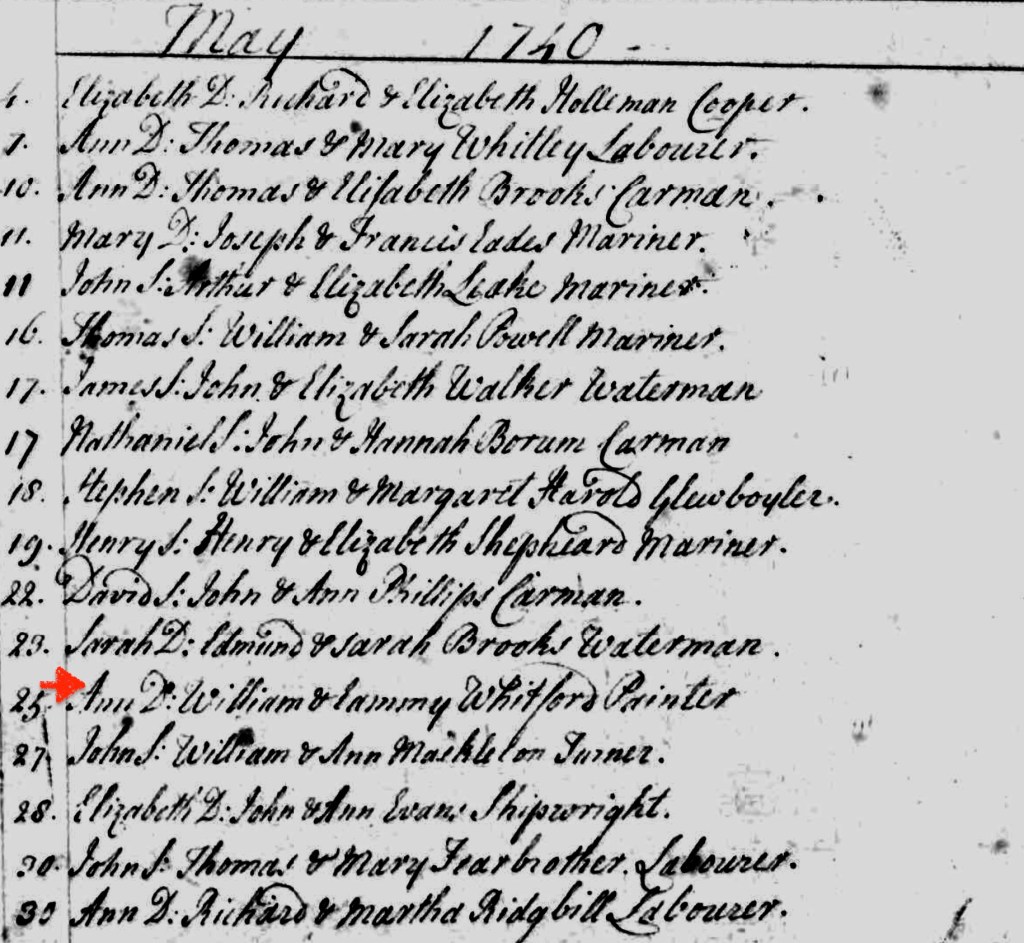

The birth registration of Judith Sarah Maxwell recorded much more information than that given when her siblings were baptised. Of particular note was the information that her mother, Catherine, was the daughter of William Whitford. Armed with this knowledge, I found an indexed reference to Catherine’s baptism, which had taken place in Southwark on 28th December 1732 in the parish church of Saint Olave on Tooley Street. Catherine was the daughter of William Whitford and his wife, Amy, and her birth date was given as 1 December 1732. I also found the baptisms of two younger siblings in the parish registers of St John Horsleydown: William in 1737 and Ann in 1740:

London, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538-1812

via https://www.ancestry.co.uk

London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; London Church of England Parish Registers; Reference Number: P71/Jn/009

London, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538-1812

via https://www.ancestry.co.uk

London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; London Church of England Parish Registers; Reference Number: P71/Jn/009

Occupations of the fathers are recorded in the original registers of St John Horsleydown. At the baptism of his son, William, in 1737, William Whitford is described as a plaisterer and at the baptism of his daughter, Ann, in 1740, a painter.

Georgian London saw a boom in house building, with rows and rows of identical terraces built. Many of these houses, though constructed from brick, had a showy stucco facade made of plaster, which was comprised of lime, gypsum, hay and straw. Stucco became a hallmark of the Georgian terrace and often it was decorated with elaborate and ornamental patterns, known as pargetting. It was then painted so William Whitford presumably did both jobs. Plaster was also used on interior walls and ornamental plasterwork was in demand on ceilings inside houses.

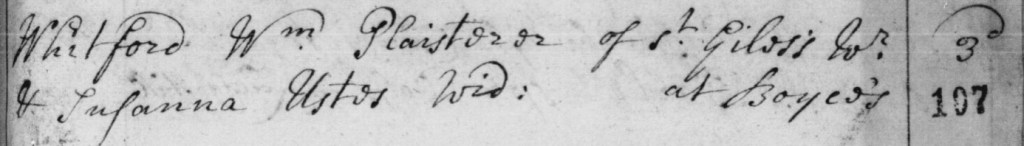

Unfortunately, I could find no trace of the marriage of William Whitford and his wife, Amy, but I did find a likely second marriage of William on 3rd May 1743, which had taken place clandestinely at the Fleet Prison. William Whitford, a plaisterer and widower, married Susanna Ustes, a widow at Boyed’s:

London, England, Clandestine Marriage and Baptism Registers, 1667-1754

via https://www.ancestry.co.uk

By the 1740s, over half of all marriages in London were taking place in the environs of the Fleet Prison, perhaps in a tavern or a coffee house, where unscrupulous clergyman who had been imprisoned for bankruptcy, were doing a roaring trade. As long as both parties consented and were of the legal age, 14 for males and 12 for females, it was perfectly legal if the marriage was conducted by a Church of England clergyman. Banns didn’t have to be published and there was no need to purchase an expensive licence. No questions were asked, and couples could marry cheaply, quickly and secretly. It wasn’t until 1753 that the resulting scandals and abuses became so great that legislation was brought in to bring these marriages to an end.

A plaisterer (plasterer) was a skilled craftsman and William Whitford would have to have been admitted to the Plaisterers Livery Company in order to practice in London. The Plaisterers Company, which received its Royal Charter in 1501, was founded to regulate the quality of plaistering and provide welfare for members and their widows.

“Azure on a chevron engrailed argent a rose gules budded or, stalked and leaved vert, between two fleurs de lys azure; in chief a trowel fessewise between two plasterer’s hammers palewise all argent handled or, in case a plasterer’s brush, of four knots tied argent handled or.”

https://plaistererslivery.co.uk/company/history

Once admitted to a livery company, a person was granted the freedom of the livery company and before 1835, you had to be a freeman of a livery company in order to become a freeman of the City of London. The City of London was controlled by the freemen, who had certain rights and privileges, such as the exclusive right to carry on a trade or to vote in an election. Searching Ancestry’s collection, “Freedom of the City of London, Admission Papers” for the surname of Whitford, I found a record for a man named John Whitford:

London Metropolitan Archive; Reference Number: COL/CHD/FR/02/0480-0487

via https://www.ancestry.co.uk

John Whitford had become a freeman on 23rd April 1725 through patrimony, which means he was born to a freeman after his father’s own admission. His father was named as William Whitford, a plaisterer and citizen of the City of London, which means that William senior was both a member of a livery company and a freeman of the City. Witnesses, who subscribed their names at the end of the document, declared on oath that John had been born in lawful wedlock after the admission of his father into the freedom of the City. The sum recorded by the date suggests that John was 21 when he was admitted and had been born in 1704. Apart from patrimony, freedom could also be granted through servitude, serving an apprenticeship to a freeman, or redemption, purchasing one’s admission.

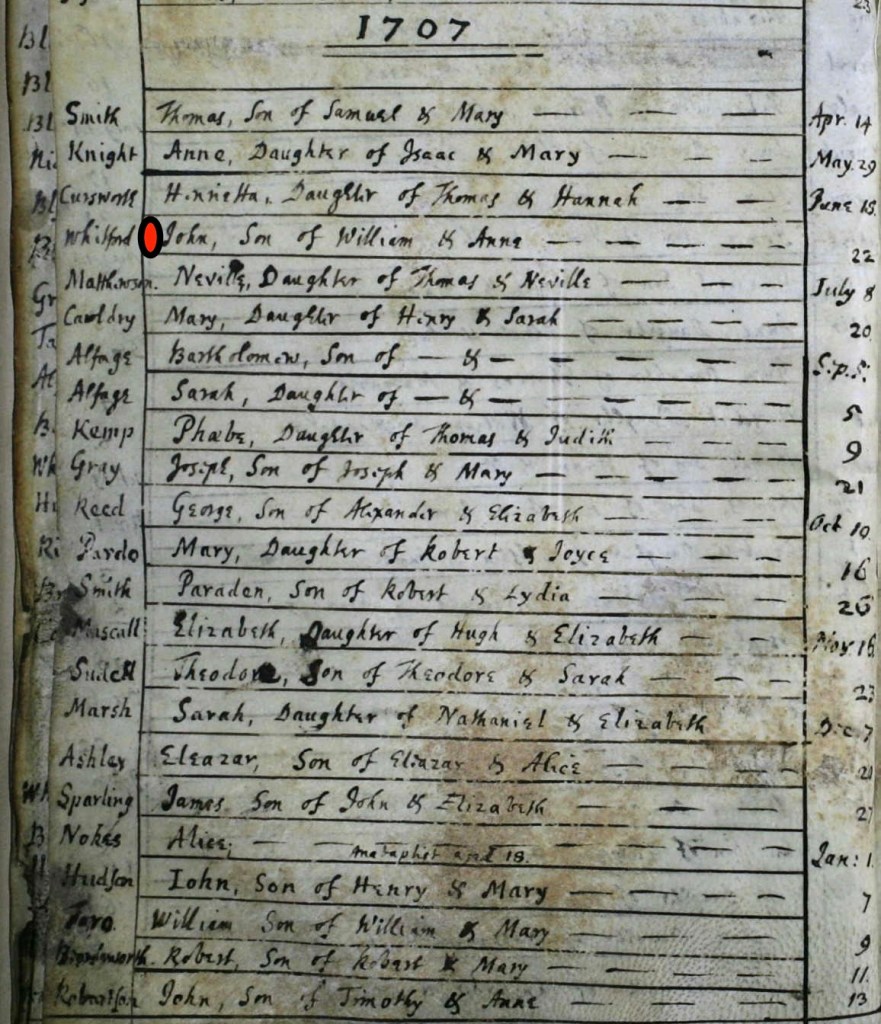

A record of a baptism of a John Whitford, the son of William Whitford and his wife, Anne, is recorded in the parish of St Alphage London Wall on 22nd June 1707:

London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; London Church of England Parish Registers; Reference Number: P69/Alp/A/001/Ms05746/002

via https://www.ancestry.co.uk

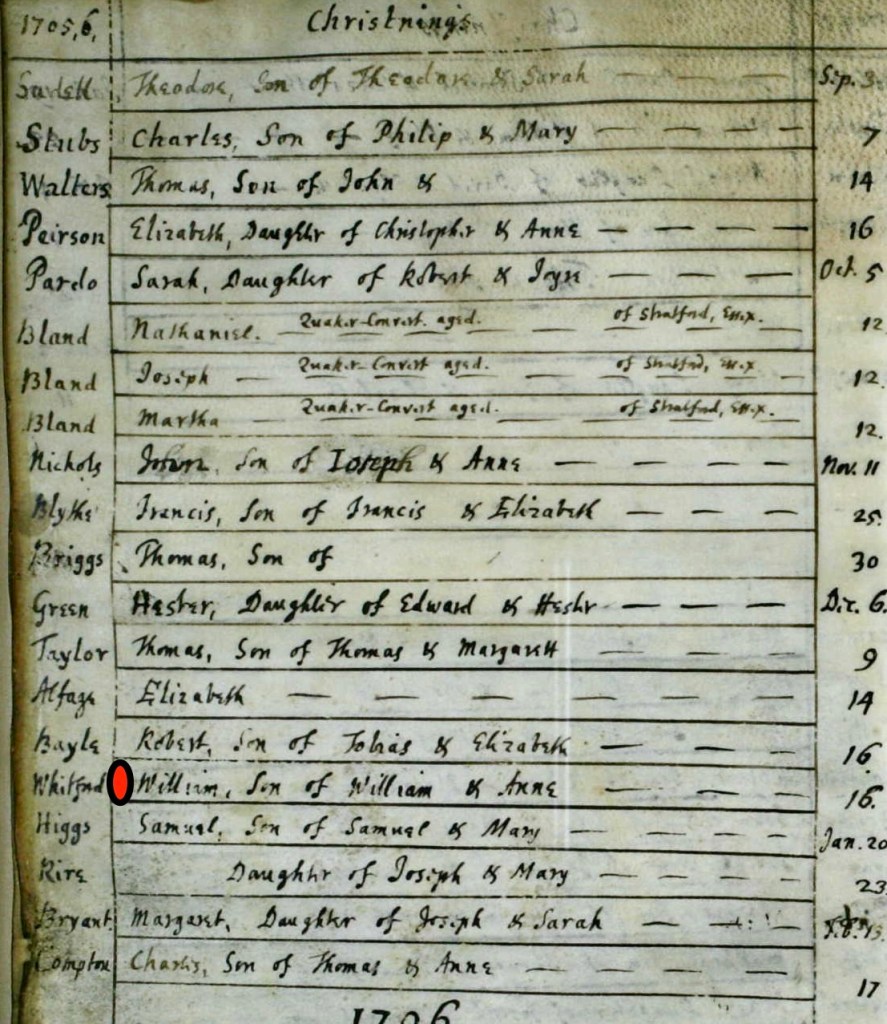

John and Anne Whitford also had another son, William, baptised in St Alphage London Wall on 16th December 1705:

London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; London Church of England Parish Registers; Reference Number: P69/Alp/A/001/Ms05746/002

via https://www.ancestry.co.uk

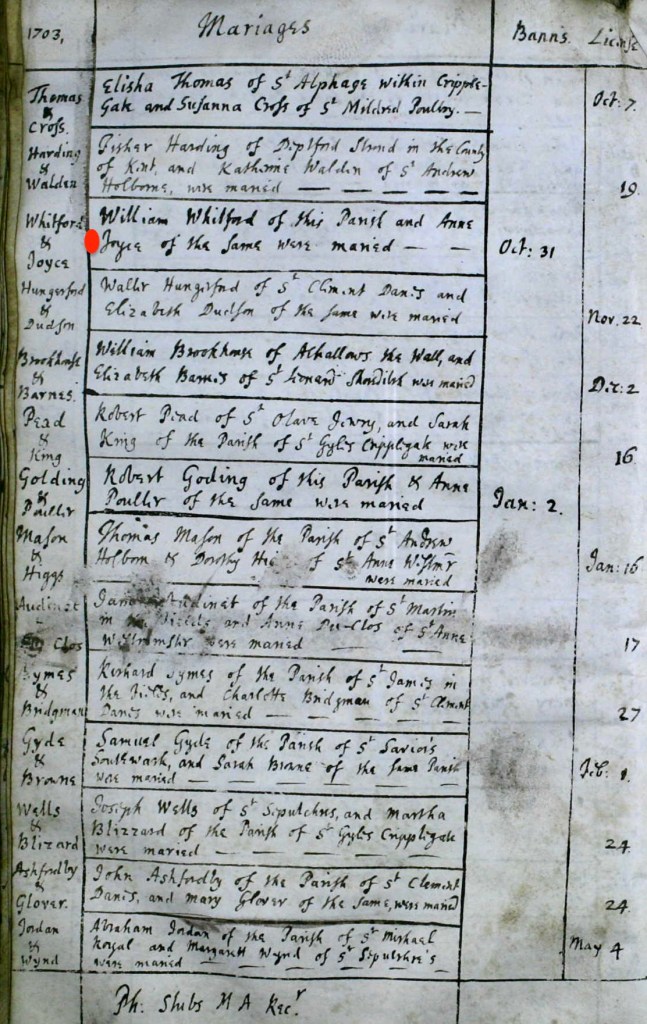

It would seem likely that this is the baptism of William, the father of Catherine though unlike his brother, John, no trace of the original record granting his freedom of the City of London has been found. The Whitford family were living in the parish of St Alphage Wall, and the Hall of the Plaisterers Company was situated in the same parish. William Whitford married Anne Joyce at the parish church on 31st October 1703:

London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; London Church of England Parish Registers; Reference Number: P69/Alp/A/001/Ms05746/002

via https://www.ancestry.co.uk

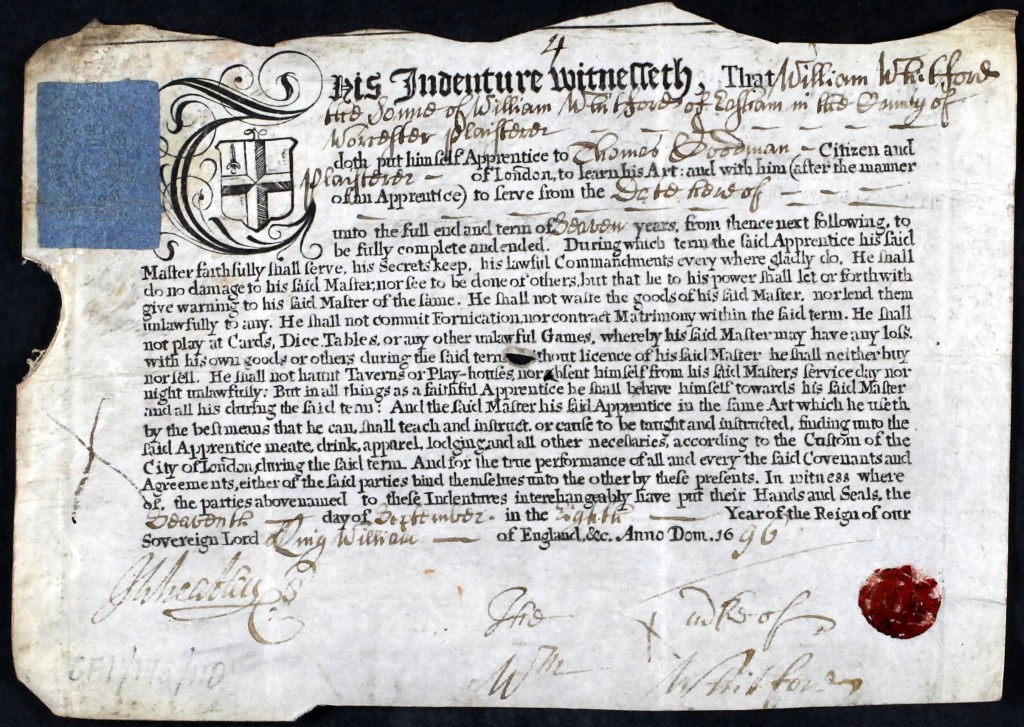

As mentioned previously, one way of gaining admittance into a livery company was through servitude, after an apprenticeship to a freeman had been completed. Apprentices typically started at the age of 14 and in return for payment (a premium), their master would teach them a trade and provide board and lodging. Apprentices had one year from the start of their apprenticeship to enrol their apprenticeship indenture with the City Chamberlain, or they would have to pay a higher fee if they subsequently applied for freedom of the City. Fortunately, the original indenture of the apprenticeship of William Whitford senior was in the City of London freeman records:

London Metropolitan Archive; Reference Number: COL/CHD/FR/02/0191-0197

via https://www.ancestry.co.uk

William Whitford, the son of William Whitford of Easham [Evesham] in the county of Worcester, plaisterer, was apprenticed to Thomas Goodman, citizen and plaisterer of London for seven years from 7th September 1696. As was standard practice, there was a long list of the rules and regulations, governing the behaviour of the apprentice. William Whitford made his mark at the bottom, Since it was an indenture, there were originally three parts to the document and the terms were written out in triplicate. The top two parts were signed and given to each respective party whilst the third part at the base of the document was filed. The indenture was cut in an irregular way so each part would have to fit together. The wavy line meant that it would be difficult to forge.

My research into the Whitford family has shown how advantageous it can be when a skilled occupation is practised by multiple members of a family. The evidence gathered from parish registers and the Freedom of the City Admission Papers revealed that there were at least three generations of Whitford plaisterers. Catherine Whitford’s grandfather, William Whitford, first arrived in London in 1696 to serve an apprenticeship with a plaisterer named Thomas Goodman and his apprenticeship indenture recorded the valuable information that he was from Evesham, Worcestershire. Given that he was around 14 year old in 1696, he was probably baptised around 1682 in Evesham, the son of a plaisterer named William Whitford. The search for the family’s roots continues.

@ Judith Batchelor 2023

What an absolute treasure trove of documents you were able to trace, Judith! A fascinating insight into one family’s occupation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this interesting insight.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As always, a fascinating and educational post. I must check the records for Dr Williams’s Library! The Ferdinando family go back and forth between the established church and dissenting ones.

I have had a little success with Freedom of the City Admission Papers, having found one for one of my 5th great-granduncles. His brother signed at the bottom, yet I haven’t found the brother’s papers (yet).

Their nephew, my 4th great-grandfather, was baptized in 1750 at St Leonard, Shoreditch, and while his father’s occupation wasn’t noted, at least the location (Webb Square) and his dob were. It’s so interesting how some registers included a lot of information, while others, the bare minimum. I’m fortunate with this line that the Ferdinando name is fairly unique, so easy to spot – though it often appears as Fernando.

LikeLike

The advantage of having London ancestors is that there are often additional record sources to find them in. It’s interesting when you see a family leave or return to the Church of England. Was there a falling out with the parish incumbent or did they meet a charismatic nonconformist preacher?

I wonder what proportion of admission registers have survived? Hopefully more of the livery company archives will be digitised too. Do you know when the Ferdinando family arrived in England?

LikeLike

Hello Judith

I always enjoy reading your posts. Ancestors with a skilled occupation was a good one.

What I have discovered about my ancestors occupations came mostly through census records.

Naval Stores played a big role in southeastern North Carolina. Tapping the long straw pine for the sap to process (using a turpentine still) into tar, pitch, and spirits of turpentine. The people were called Tar Heels and North Carolina was known as the Tar Heel State. My ancestors were also small farmers and Coopers (barrel makers). Some of the females had occupations as spinsters (using the spinning wheel).

All of these took skills.

Jimmy Batchelor

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Likewise it is interesting to learn about occupations in your part of the world. I didn’t know anything about tar heels.

LikeLike

Just catching up with this Jude. As ever a truly wonderful blog and an absolute treasure trove of documents you were able to trace your ancestor with. A fascinating insight into one family’s occupation and lots to learn for all of us

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I would love to investigate the livery company records that are not online and discover even more treasures. In particular, those of the Company of Watermen and Lightermen.

LikeLike