HMS Vanguard (1909) with Sister Ship of St Vincent Class

Watercolour “Dirty Weather by A.C.B. Cull 1912

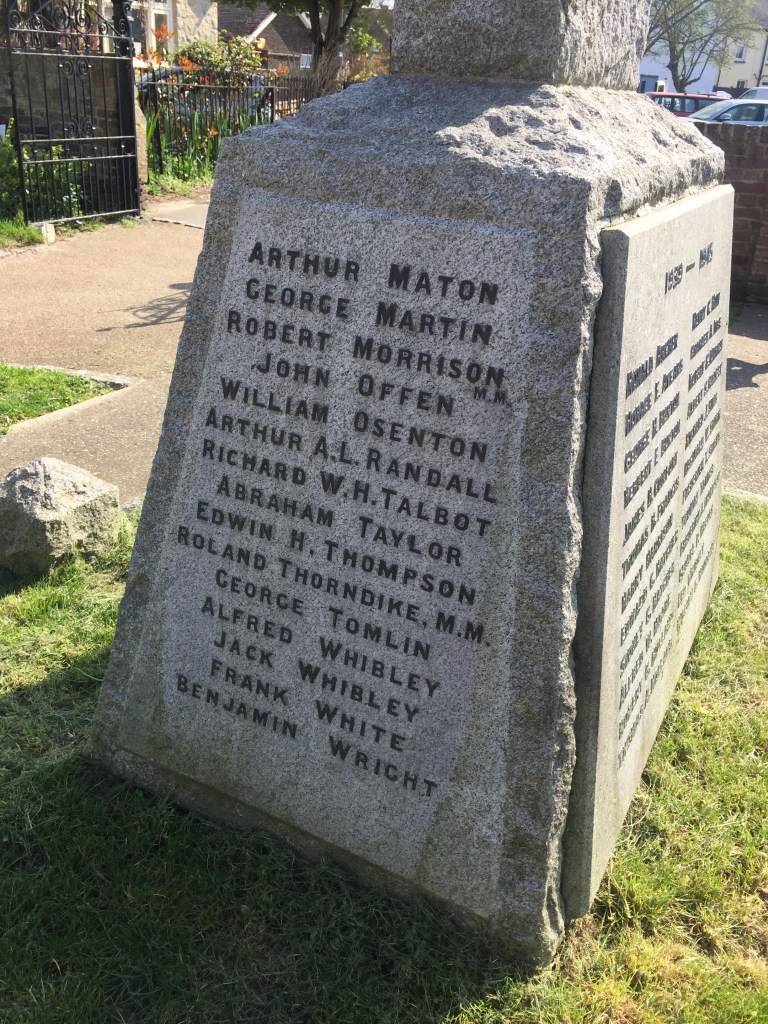

In a corner of the churchyard of St Helen’s, Cliffe, Kent, at the base of a stone cross, are the names of villagers who gave their lives for their country in the two World Wars. One of those commemorated is Arthur Maton, the nephew of my great grandmother, Elizabeth Jane Maton. His life was tragically cut short by a terrible explosion on board HMS Vanguard in 1917, one of the worst naval disasters in British history. Arthur was a young man aged just twenty years old.

Early Life

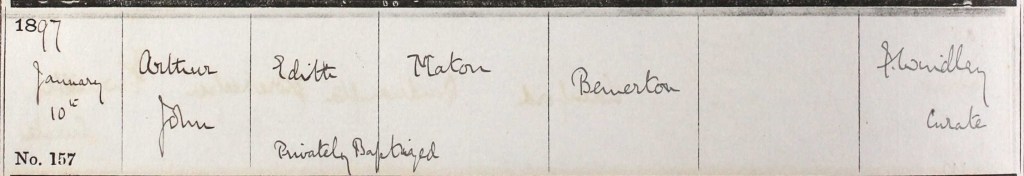

Arthur John Maton was born on November 19 1896 in Bemerton, Salisbury, Wiltshire. He was the son of Edith Agnes Maton, a young, unmarried mother who had probably been working as a servant when she fell pregnant. A few years previously, when the 1891 census was taken, she was a nurserymaid for the Reverend John D Morris and his wife, Jessie, living at St Edmund’s Rectory on Manor Road in Salisbury. She decided to have baby Arthur privately baptised, perhaps because he was a sickly baby or because there was no father on the scene, on January 10th 1897. This event is recorded in the parish registers of Bemerton, Salisbury, where Edith had grown up with her eleven brothers and sisters:

Parish Registers of Bemerton, Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre;

Reference Number: 930/30

New Life for Edith Agnes Maton

Later that year, in the autumn of 1897, Edith married Sidney Hatcher, an agricultural labourer from Alderbury, a village three miles south-east of Salisbury. He was an older man, around fifteen years her senior, and they had two children of their own, Sidney Herbert (b. 1899) and Viola Evelyn (b. 1900). They family made a home at Nursery Cottage in Alderbury, where they were living in both 1901 and 1911, but there was no sign of Arthur in the household. This suggests that Sidney Hatcher was not Arthur’s father. So what had happened to little Arthur?

Move to Kent

Arthur was, in fact, many miles away in Kent, living with his maternal grandparents, Thomas and Sarah Ann Maton. It would seem that Edith had left baby Arthur with her parents for them to bring up, perhaps because her new husband had not wanted to welcome a child that was not his into their home. Sometime between 1891 and 1901, Thomas and Sarah Ann Maton had decided to move to leave Wiltshire to join their eldest daughter, Elizabeth Jane Batchelor, in Kent. She had married a prosperous farmer and prominent local Wesleyan Methodist, George Alfred Batchelor in 1885. George’s father, James, a farmer and a publican, had bought a farm called Gattons on Cooling Street in Cooling, Kent:

Thomas and Sarah Ann Maton were living at Gattons Farmhouse with their youngest children when the 1901 census was taken. Included with them was their grandson, Arthur, aged four. Thomas Maton had found work as a farm labourer and may well have been working for his son-in-law, George Batchelor, but here, he is described as the head of the household, whilst his daughter’s father-in-law, James Batchelor, (described as a retired farmer), was rather cheekily described as being a “boarder”:

https://www.ancestry.co.uk RG13 718 32 14

The National Archives (U.K.)

Whether Edith kept in touch with her son is unknown. She had her own young family and was living a long distance away so contact must have been limited. Perhaps she was just happy that he was being well-cared for by her parents and they, in turn, welcomed the company of their young grandchild.

Delivering Milk

By 1911, the Maton family had moved to the neighbouring village of Cliffe and their rather more modest home was 2 Winifred Terrace, Higham Road:

Thomas Maton had retired from farm work and had his own business as a milkman, as can be seen on the 1911 census schedule. Delivering milk was a less strenuous job for a man of his age and Thomas had his young grandson, Arthur, now aged fourteen, to help him:

https://www.ancestry.co.uk RG14 3856 32

The National Archives (U.K.)

Wartime

With mounting tensions between Great Britain and Germany, hostilities broke out in the summer of 1914 and despite predictions that it would soon be over, the War dragged on. Did Thomas fear that his young grandson might get called up ? With losses increasing, fresh recruits were needed and the pressure was on young men, particularly those without dependents, to sign up. The Kent Messenger and Gravesend Reporter, in an article dated November 22nd 1914, “How Not to Recruit – Rector’s Wild Talk” told how Canon H.B. Boyd, the Rector of Cliffe, had chaired a recent recruiting meeting in Cliffe. When volunteers were not forthcoming, he accused the villagers of being a “herring-gutted lot!”

A few months later, Arthur lost his grandfather, Thomas Maton, the man who had been a father to him since he was a baby. Thomas Maton died on April 21 1915 aged seventy three, leaving Arthur to take over the business. The following month, the newspapers were full of the sinking of the Lusitania, an unarmed passenger ship that was struck by a German torpedo and sunk with the loss of nearly 1200 lives. More and more were signing up and Arthur decided to join them.

Imperial War Museum, London

Royal Naval Service

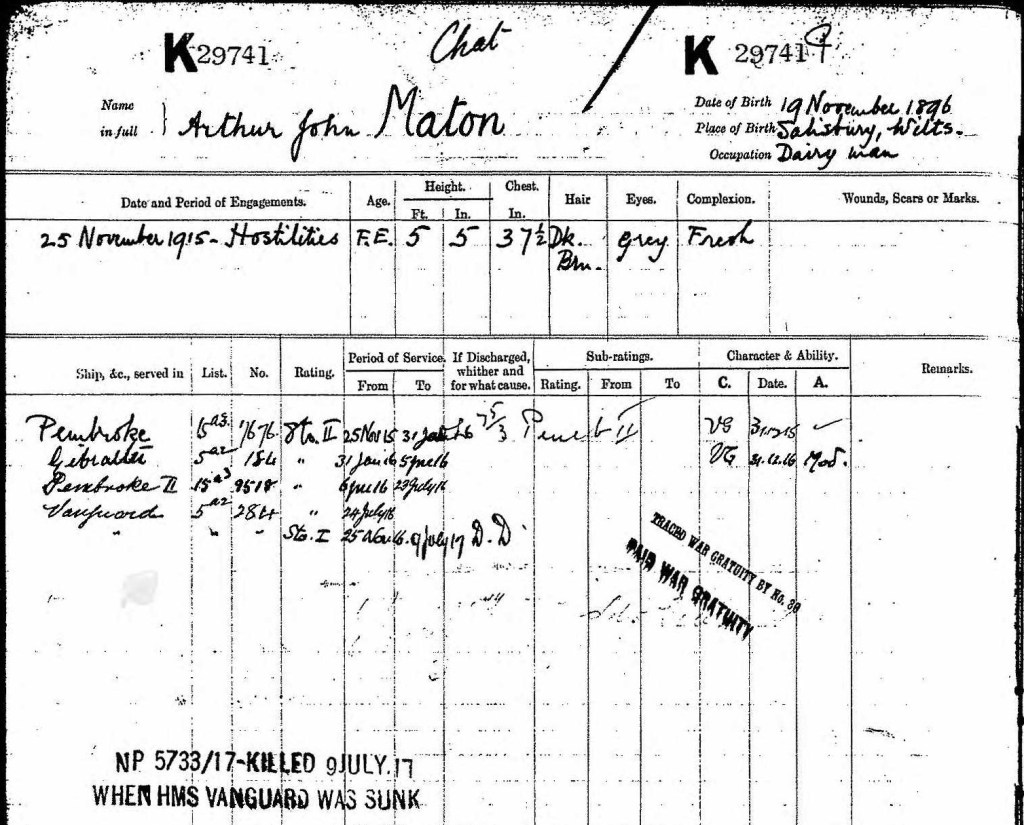

It was a grey Thursday morning on November 25 1915, when a knock at the door of the office of the recruiting officer at the naval barracks of HMS Pembroke, Chatham, announced the arrival of Arthur John Maton, who had journeyed there from Cliffe. A young, fresh-faced youth, with a shock of dark brown hair and grey eyes, Arthur walked into the room, looking nervous but excited. He had just celebrated his nineteenth birthday the week before and was ready for adventure and to serve his country. After being assessed, it was decided that Arthur would make a good stoker, since he was of medium height and young. To work in the stokehold on board ship you needed to be strong with a lot of stamina. Shovelling coal to create a constant supply of steam, the ship’s lifeblood, was a hot and arduous job.

Six weeks later, at the end of January 1916, Arthur finished his land-based training at HMS Pembroke and joined HMS Gibralter. HMS Gibraltar was a useful posting for new recruits to gain experience and further skills, as it was mainly involved in shore defence, and used as a depot ship in the Shetlands. However, Arthur’s service on HMS Gibraltar was short-lived and after returning to HMS Pembroke for another six weeks of training in June 1916, he joined HMS Vanguard on July 24th 1916.

HMS Vanguard

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Vanguard_(1909)

H.M.S. Vanguard was a relatively new ship, having been launched in 1909. It was one of three St Vincent-class dreadnoughts and had participated in the Battle of Jutland in May 1916, only a month before Arthur joined her. Over the next few months, she was involved in North Sea patrols.

Arthur was obviously competent in his job for on November 25th 1916, after completing his first year in the Navy, he qualified as a 1st Class Stoker. His conduct was described as “Very Good”. Undoubtedly, his elderly grandmother, Sarah Ann Maton, was very proud of what he had achieved.

Explosion

Whilst it was wartime, and lives were frequently cut short, no one could have predicted that Arthur’s life was to be ended, not by enemy action but by a devastating internal explosion on board HMS Vanguard. Shortly before midnight, on 9 July 1917, whilst the ship was anchored at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, there was a series of explosions in the magazine, perhaps due to faulty cordite. Pieces of the ship and human body parts were blown sky high, landing on neighbouring ships in the harbour. She sank almost immediately and with only two survivors, there was almost no one to rescue, although there were 845 men on board. Arthur, aged just twenty, was killed.

First World War.;

Class: ADM 242; Piece: Piece 009; Piece Description: Piece 009 (1914 – 1919)

The National Archives (U.K.)

UK British Army and Navy, Birth Marriage and Death Records 1730-1960 https://www.ancestry.co.uk

The National Archives (U.K)

Royal Navy Registers of Seamen’s Services, 1848-1939

https://www.ancestry.co.uk

Those Left Behind

The death of Arthur must have been a devastating blow to his family. Sarah Ann, his grandmother, had died earlier that year on February 19 1917, aged seventy two, so she was spared the terrible news of his death. In the official records, his mother, Mrs S. Hatcher, now of Swiss Villa, Whaddon, Nr Salisbury, is named as his next of kin. She was notified of his death and would have received the war gratuity:

UK Commonwealth War Graves Memorial Register, Chatham 1914-1921, Chatham Memorial Part 4, https://www.ancestry.co.uk

Memorials

Arthur has no known resting place as, like most of his fellow sailors, his body was never recovered. However, he is commemorated on the Chatham War Memorial as well as the war memorial in the churchyard of Cliffe, the village where he had spent his boyhood. His name is recorded here along with those of many of his schoolfellows, whose lives were also cut short.

Postscript

I was inspired to write about Arthur’s story after hearing about a group called Vanguard Crew Photos: https://www.vanguardcrewphotos.org/. The purpose of the group is to put a face to every name and currently, (July 2025), they have found photographs of 315 of the crew members, just over a third of the casualties. Sadly, there is no known photograph of Arthur Maton, although his service records give a good impression of what he looked like. Perhaps one day a photo of him will come to light but regardless, he is remembered.

© Judith Batchelor 2020

(updated July 2025)

Fascinating story – great work. Thanks.

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed reading it. Thanks!

LikeLike

BRAVO ZULU; GREAT RESEARCH…LET US KEEP W.W.I AND W.W.II HISTORY, ALIVE!!!

Brian Murza, W.W.II Naval Researcher-Published Author, Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada.

LikeLiked by 1 person