A few months ago I was invited to talk with some fellow genealogists and historians on the subject of occupations, and their importance to family history on the new “Really Useful Podcast” produced by the Federation of Family History Societies. We had a really interesting discussion, which you can listen to here: https://www.familyhistoryfederation.com/podcast (Series 1, Episode 1). Knowing what our ancestors did in their every day lives is a very important aspect of our family history research, but too often, particularly at earlier dates, we know very little about their world of work. This ignorance can be compounded by indexes that frequently miss out occupational information that has recorded in the original records. Yet knowing about our ancestors’ work can be very helpful, both in understanding their lives better and in tracing remoter generations.

Occupations can help explain migration patterns. After the Industrial Revolution, many agricultural workers flocked to the cities from the countryside to find jobs that offered better pay and more stability, especially when the rural economy was going through depression. Similarly, workers who had formerly been working in cottage industries left their homes for the cities to find work in factories, as goods began to be massed produced on an industrial scale. Since time immemorial, the search for a better standard of living has been a primary motivation for moving to a different part of the country, or even the world. There are many examples of this, such as Cornish miners who moved to the north-east to work in the coal mines, or to South Wales, when the mining industry in Cornwall suffered a severe downturn. When economic conditions are bad and work is scarce, people move to where they can find new jobs.

Occupations can also assist with identification. Especially prior to the 19th century, a common problem is how to distinguish between two individuals of the same name, particularly when you have a common surname in your family tree. If you have two individuals named John Smith who were born at roughly the same time and in the same area, it can be difficult to know which candidate is your own ancestor. Knowledge of an occupation may be the only means of distinguishing between them.

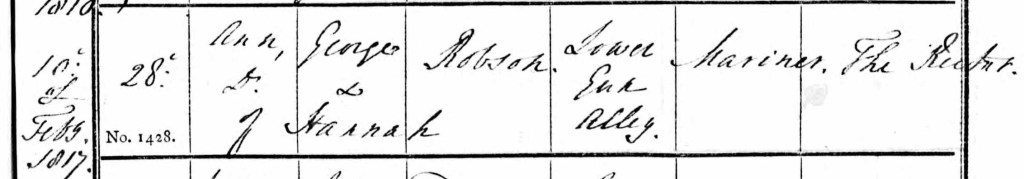

Fortunately, there are many different sources in the Victorian period and in the early 20th century that record out ancestors’ occupations, notably census returns and General Registration (GRO) certificates. Using these we can trace the progression of an ancestor’s career or even see how they did different jobs during their lifetime. The 1921, to be released in January 2022, will even provide information on a person’s employer. Newspapers and trade directories are also primary sources for a person’s employment. With regard to parish registers, Rose’s Act of 1812 provided printed forms for baptisms, which included a column for occupations to be recorded so baptisms after this date contain this important information:

Ann’s father, George, is described as a mariner.

London Church of England Parish Registers 1813-1906 p93/geo/008

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) via http://www.ancestry.co.uk

A person’s occupation can change over time. Many of our ancestors were quite versatile and changed their job more than once during their lifetimes. One of my ancestors, Thomas Maton, as a young man, followed in his father footsteps and found work as an agricultural labourer and then a gardener. He then obviously thought he would have better prospects if he did something different so he joined the police. This was undoubtedly a tough and sometimes a dangerous job. After a few years he left to find work as a railway signalman. Finally, when he was old, he worked as a milkman, which probably wasn’t too strenuous for a man of his age. The changes in his employment can be traced through the census and from GRO certificates. However, in some instances, it is not always so easy to know if you are looking at the same person, when the occupations are diverse and a person is very mobile.

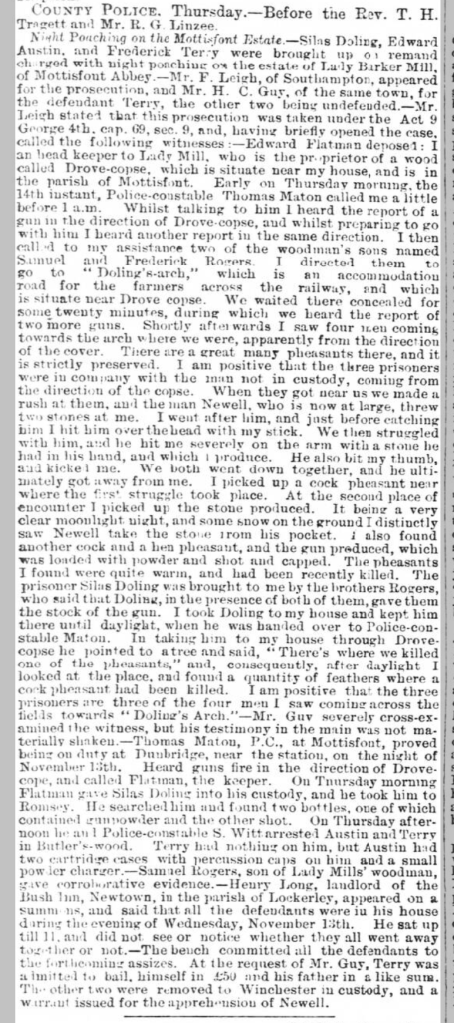

Newspapers are another wonderful source for knowledge of an ancestor’s occupation. As mentioned, my ancestor, Thomas Maton, joined the police. I have found several newspaper articles that detail some incidents in his career, which give you a flavour of what his job involved. This is an account of him challenging poachers on the Mottisfont Estate in Hampshire:

Some organisations kept their own records. I have been able to find information on the police career of Thomas Maton in the records of Hampshire Constabulary. The police records provided details of his age, place of birth, physical description, his past employer, the fact that he could read and write, his marital status, the number of children he had, his membership of a Friendly Society, his misdemeanours and the dates of his appointment. Since I have never seen a photograph of Thomas Maton, it is wonderful to have an impression of what he looked like.

Knowledge of an occupation can also give you a real appreciation of your ancestor’s day-to-day life. Most would have had long working hours, with only Sundays off. My great grandfather, George Henry Powell, was a cooper, and made barrels for a living from staves of oak wood bent and shaped, held together with wrought iron hoops. He worked in the cooperage of a cement factory, as barrels of cement were loaded onto ships and exported around the world. What tools would he have used, how did he acquire his skills, did he wear any special clothing and what was his weekly wage? These are the sort of questions to ask for any ancestor with a trade. By looking at George’s family, it becomes apparent that he must have been taught the trade by his maternal uncle, Henry Thatcher Woodbine. Henry was also employed as a cooper at the cement works and lived a few doors away from George’s family. Paying attention to occupations can sometimes reveal family connections that may not otherwise be apparent.

If your ancestor had their own business, you may find an advertisement, either in a newspaper or a trade directory, such as the one below for D. Hill, a “Practical Watch and Clock Maker, Working Jeweller &.c”, which appears in a local newspaper in Wiltshire in 1868:

Advertisements for jobs can also be a good way of finding out what a specific job involved, the qualifications sought, the rate of pay and the main duties required.

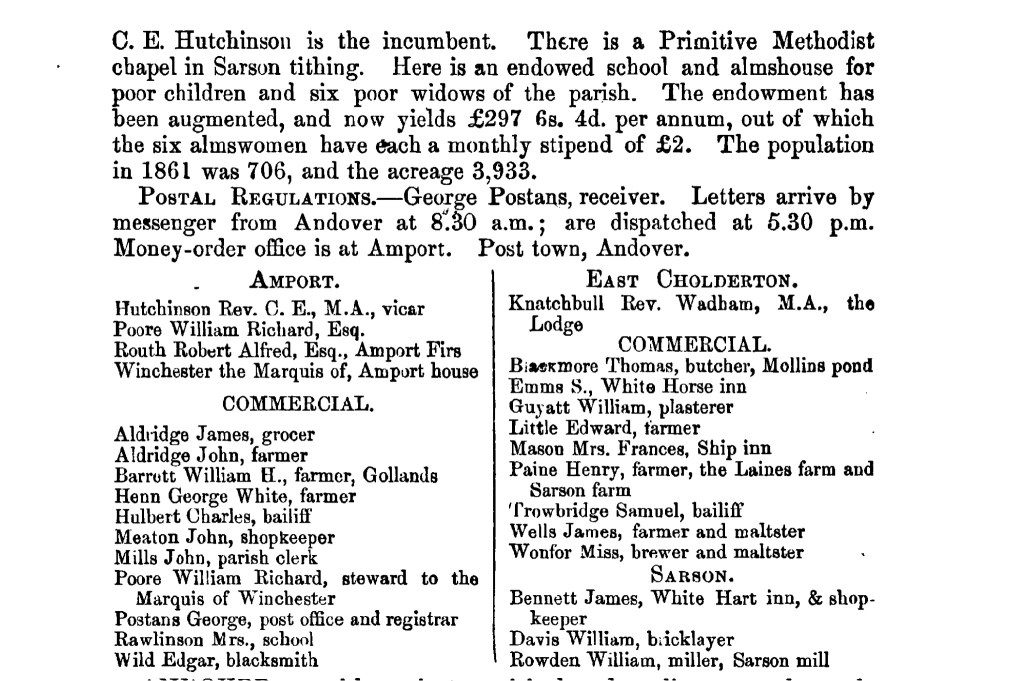

Trade Directories can be an important source for following changes in occupation and provide evidence of relationships. Relatives often took on the family business at the same address: a son commonly followed in his father’s footsteps. Specific trades often ran in families, so other individuals following the same trade, particularly if it is not all that common, may well be relatives. For example, a bedstead maker named John Grinstead was living in Woolwich, Kent, but died in 1848 aged 53, before the 1851 census was taken, so his place of birth is unknown. A trade directory reveals that a William Grinstead was a bedstead maker in nearby Greenwich, Kent. William is still alive when the 1851 census was taken, aged 55, and from this, you know that he was born in Northwold in Norfolk ca. 1796. Armed with this knowledge of William’s place of birth, you may be able to trace John’s baptism and prove that he and William were brothers. If you ancestor owned or worked for a business, you can also find out when it was in operation and its premises, by searching through consecutive trade directories.

Sadly, women’s employment is typically underreported although they undoubtedly contributed to the family income, especially in areas where factory work was available after the Industrial Revolution. At earlier dates, many women would have been involved in cottage industries, helping to supplement their husband’s wages through their industry at home. The focus in census returns is generally on the occupation of the head of the household but there is no doubt that many working class wives had jobs too. They would also help out in the business if their husband had a trade or shop. Single women and widows are most likely to have their occupations recorded. They often got by through working as dressmakers or as laundresses in later life. Many of my female ancestors also worked as domestic servants prior to their marriage, as is evidenced from census returns. Information on women’s work may also be found in newspapers and trade directories. This trade directory reveals that there were several women who were in charge of businesses in the small village of Amport in Hampshire:

Mrs Frances Mason is running The Ship Inn and Miss Wonfor is a brewer and maltster. In addition, Mrs Rawlinson is recorded as the schoolmistress.

Occupations may even help you determine how couples met. (Read my article on Courtship here: https://genealogyjude.com/2021/09/25/courtship/) My husband’s family were mathematical instrument makers in Wapping, London. William Ford had his own business as a mathematical instrument maker, close to the docks, and had a daughter, Esther. She married a fellow mathematical instrument maker, John Cronmire, who must have been an associate of her father. Did she assist her father in the business, perhaps serving in the shop? If your ancestor was an artisan, there is always the possibility that an item they crafted might have survived to the present day. Wouldn’t it be incredible to hold something in your hands that had been made by an ancestor!

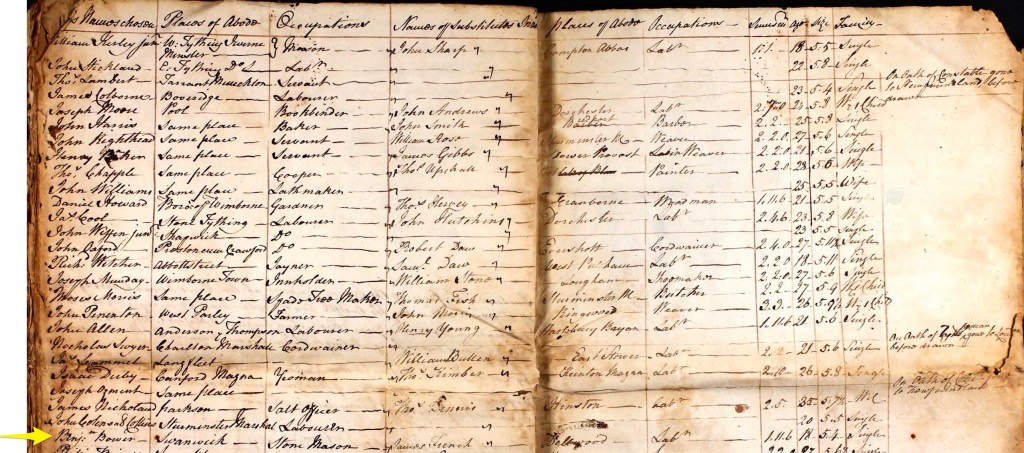

If your ancestor saw service, there are wonderful military records that provide personal details about them and information on their career. A person’s occupation prior to their service was also recorded when they signed up. Some large record collections are the Army Service Papers of WO 97 1760-1913, or Royal Navy Ratings’ Continuous Service Records in ADM 1853-1928. Militia Records, where they survive, can also be a useful source for occupations. The Militia Act was passed in 1757 to form a professional national military service. Men aged between 18 and 45 (lowered from 50 in 1762) were selected by ballot to serve on a part-time voluntary basis in infantry regiments. A man could pay for a substitute to serve in their place. The occupation of each individual selected (or a substitute) is given:

Benjamin Bower, a stone mason of Swanwick, Dorset, paid for a substitute, James French, a labourer, to take his place in the militia. A physical description of James French is given, his age, and the fact that he is single is noted. The document can be dated ca. 1767-1769 so it is incredible to have this information on an ordinary 18th century person.

If you ancestor worked for a company, it is possible that further information on their employment might be available if the records have survived and been deposited. The railway companies were big employers and kept good records on their staff. Several of my ancestors left their villages in Wiltshire and found work with the Great Western Railway and I know a lot about their employment, their specific jobs, location and pay from the Company’s surviving Staff Registers. To trace business records, the Discovery catalogue of the National Archives should be your first port of call. A Guide to Tracing the History of a Business by Dr John Orbell, available at good reference libraries, will give you some ideas on sources. If a company is still in operation today, they may still be in possession of their records and have their own archivist. There are also sources and archives for specific occupations. There is a useful blog on sources for ancestors in the theatre, for example, here: https://www.family-tree.co.uk/useful-genealogy-websites/top-resources-for-tracing-your-theatre-ancestors/. There are also specific sources and records for those that served in the professions such as law, the church and medicine.

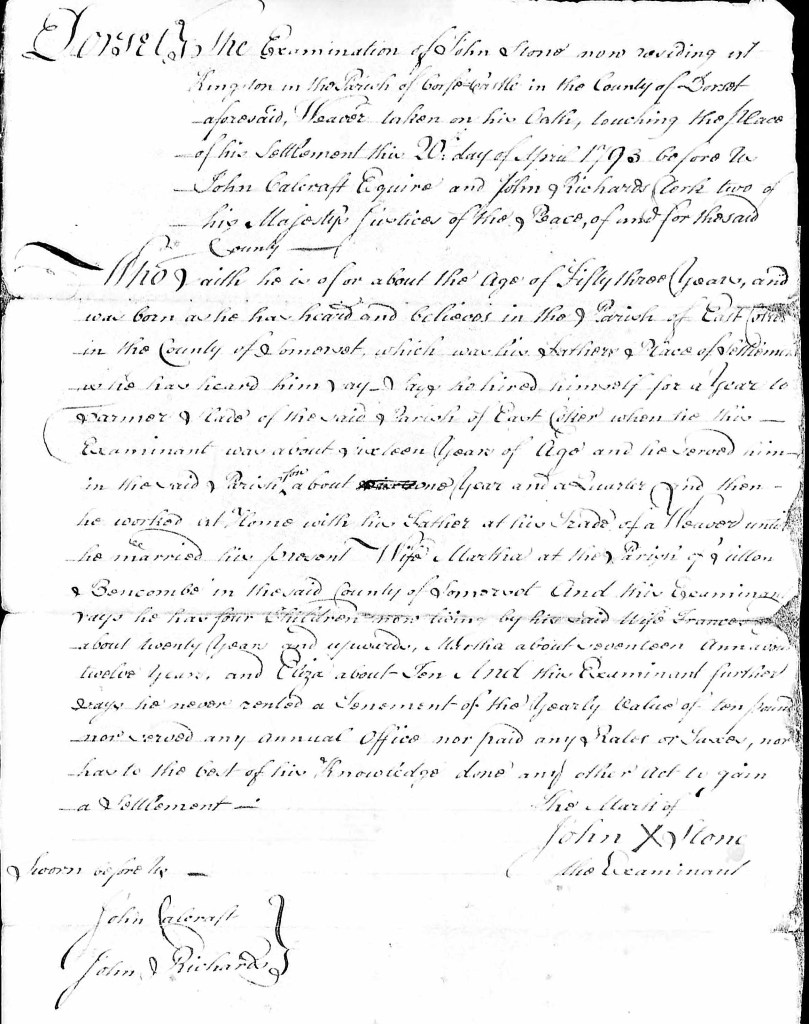

Unfortunately, parish registers prior to 1813 rarely record occupations. The amount of information recorded was up to the incumbent of the parish but it is rare for an occupation to be noted. However, parish records may provide the answer. Accounts of the overseers of the poor list payments to those in need, or parishioners who supplied goods to the parish, as well as those who contributed to the poor rate. An occupation can sometimes be deduced, if, for example, a person was given money for making a coffin; this indicates that they were a carpenter by trade. Similarly, records produced as a result of the poor laws can contain occupational information. A settlement examination, for example, may give the occupation of the person along with details of their employment history. Here is the settlement examination of John Stone of Kingston in the parish of Corfe Castle, Dorset in 1793:

Dorset History Centre; Settlement Examinations; Reel: MIC/R/1478; Reference Number: PE/COC: OV 188/1 – 188/260 via http://www.ancestry.co.uk

Dorset The Examination of John Stone now residing at

Kingston in the Parish of Corfe Castle in the County of Dorset

aforesaid, Weaver taken on his Oath, touch the place

of his settlement this 20th day of April 1793 before us

John Calcraft Esquire and John Richards Clerk two of

his Majestys Justices of the Peace, of and for the said

County---------

Who saith he is afor about the Age of Fifty three Years, and

was born as he has heard and believes in the parish of East Coker

in the County of Somerset, which was his Fathers Place of Settlement

as he has heard him say Says he hired himself for a Year to

Farmer Slade of the said Parish of East Coker when he this

Examinant was about sixteen Years of Age and he served him

in the said Parish for about one Year and a Quarter and then

he worked at home with his father and his Trade of a Weaver until

he married his present Wife Martha at the Parish of Sutton

Bencombe in the said County of Somerset And this Examinant

says he has four Children now living by his said wife Frances

about twenty Years and upwards. Martha about seventeen Ann about

twelve Years and Eliza about Ten And this Examinant further

says he never rented a Tenement of the yearly Value of ten pounds

nor saved any annual Office nor paid any Rates or Taxes, nor

has to the best of his Knowledge done any other Act to gain

a Settlement.

The Mark of John X Stone

the Examinant

Sworn before Us

John Calcraft

John Richards

This settlement examination reveals that John Stone believed he was born around 1740 in East Coker, Somerset. When he was about sixteen years old, he went to work for Farmer Slade in East Coker for a year and a quarter. He then went back to work as a weaver for his father, who followed that trade. There is further information on his two wives and four children.

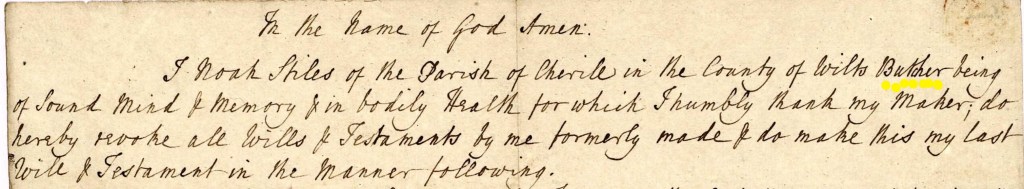

Probate records, at any date, are another important source for occupations. At the beginning of a will, for example, the description of the testator, (if a man), will give their occupation:

Noah Stiles of Cherhill, Wiltshire, who made his will in 1741, was a butcher! Of course, many people did not leave wills but probate inventories may provide clues to a person’s occupation judging by their personal possessions, as these can include the tools of their trade.

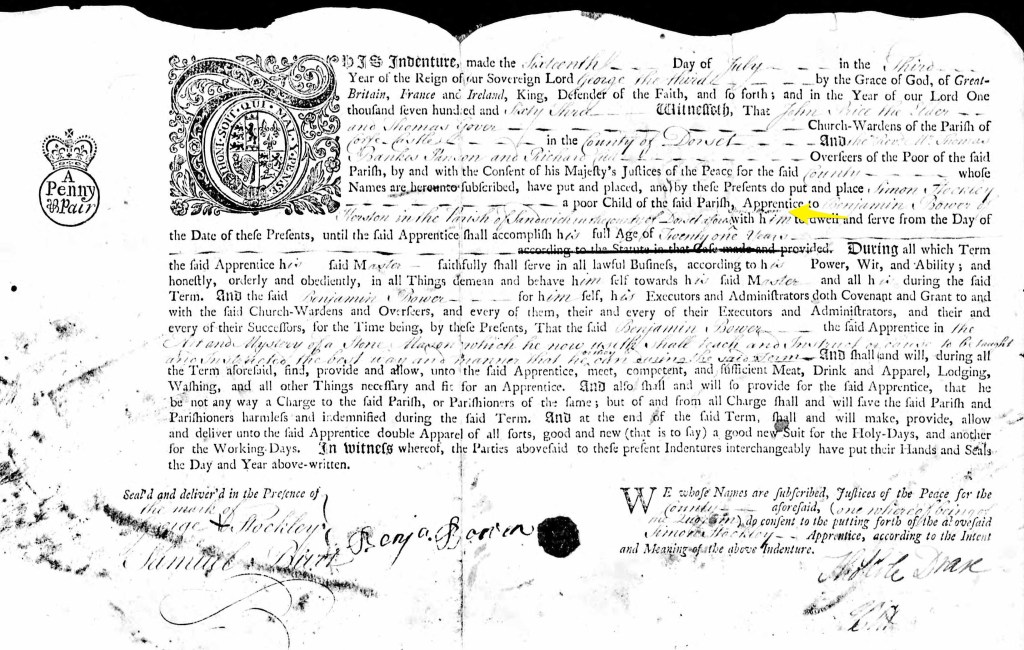

Records associated with apprenticeship are an important source for occupations. In 1550, the Statute of Artificers brought in a system of apprenticeship. Typically, an apprentice would learn a specific trade from a master for a term of seven years, beginning at the age of 14. The apprentice would receive board and lodging and the master would receive a premium (and free labour) in return. Upon completion of a masterpiece, the apprentice would gain the right to practice a craft. Apprenticeship was also one of the main ways of joining a guild, which often went hand in hand with becoming a freeman of a city. From the mid-1550s to 1751, apprenticeship records are particularly useful as they provide the names of the apprentice’s parents, occupation and place of residence. After this date the system went into decline in favour of wage labour though guilds continued to enroll apprentices, and parish apprenticeship remained a popular way of getting children off the hands of the parish and teaching them a useful trade. The indenture below (evidenced by the wavy line), is the parish apprenticeship for Simon Stockley, a poor child of Corfe Castle, Dorset, who was apprenticed to Benjamin Bower, a stone mason of Herston, Sandwich, Dorset on July 16 1763:

Note that the indenture is witnessed by George Stockley, who may well have been the father of Simon.

Records of the guilds and livery companies will provide the occupations of members though as time went, you didn’t have to follow that specific occupation to be a member. Their records will be found in city record offices, county records and the Guildhall Library in London. A collection of apprenticeship records for fifty City of London livery companies can be found on FindMyPast: http://www.findmypast.co.uk

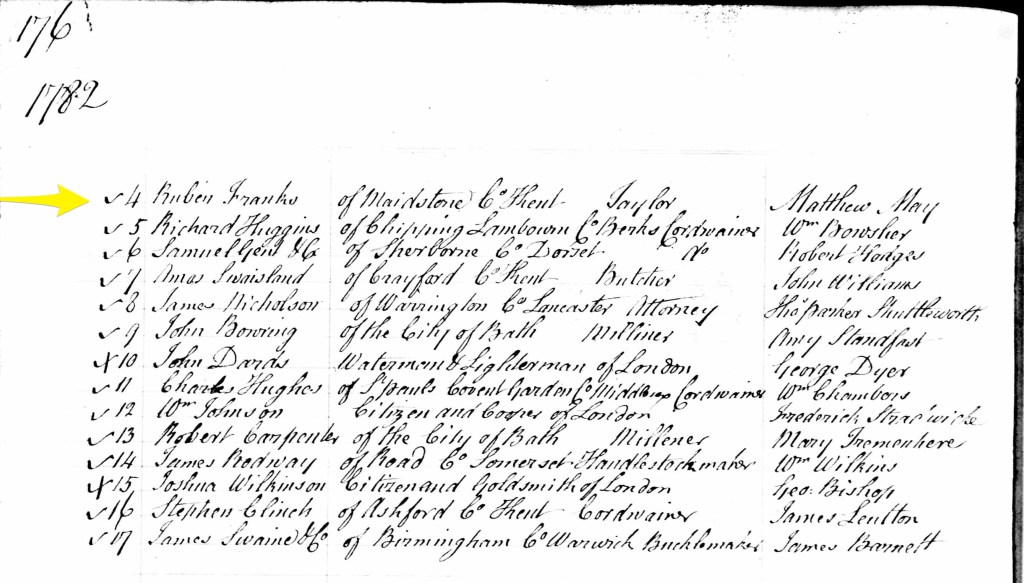

Tax was also paid on apprenticeships and records of the duty paid often survive whilst the original indenture does not. Reuben Franks, the brother of my ancestor, Mary Franks, appears as a Master in the UK Register of Duties Paid for Apprentices’ Indentures 1710-1811:

Reuben Franks is a taylor [sic] of Maidstone and had an apprentice, Matthew May. He paid a tax of £4 in 1782.

In many ways, this article just scratches the surface in terms of the different sources that can provide information on an ancestor’s occupation; many contemporary records can provide you with this information. You can also further your research by searching for local history books and websites that might mention your ancestor and their occupation: there could even be a photograph! My great great grandfather, Ann Waters Thorndike ran the family business, The Victoria Inn in Cliffe, Kent, after the death of her husband in 1890 and there is a wonderful photograph featuring her and her family on a local history website. The Society of Genealogists also has a very good series of books that cover specific occupations with the title ‘My Ancestor Was…..”. There are many wonderful museums to visit too where you can find out more about an ancestor’s working life. A few museums which spring to mind are the Museum of Rural Life, the Black Country Living Museum or the National Coal Mining Museum. There are also many local museums that will provide you with information on local crafts. If your ancestor was in the Army, excellent regimental museums will tell give you a much greater appreciation of their career than just documentary sources alone. A useful resource on all sorts of occupations can be found on Genuki: https://www.genuki.org.uk/big/Occupations. This website also contains some useful links to lists of obsolete occupations.

The aim of this article is to encourage you to seek out more information on the employment of your ancestors. Their jobs were such an important feature of their lives, yet often we know so little about what they involved. Particularly prior to the Victorian era, we may not even know what jobs they did, yet there are sources beyond parish registers that can provide this information. Knowing more about your ancestors’ occupations will enrich your appreciation of their lives, as well as helping you trace your family tree.

© Judith Batchelor 2021

As an American, I am often stumped by unfamiliar terms when researching my overseas ancestors. What is a “settlement examination,” and what is it used for? Where might they be recorded? In court records? They appear to be a goldmine!

LikeLiked by 1 person

These records can indeed be a goldmine. I should write a blog about them! For now, I will try to give you a brief explanation.

A Settlement Examination is a record that came about as a result of the English Poor Laws, which established the concept of settlement. If you became in need of support, it was the responsibility of your place of settlement to provide for you. There were several different ways that a person could gain settlement but often it was the place where someone was born. Parishes did not want to support just anybody, and “examined” a person who could be in need of help to establish their place of settlement. These documents can provide a mini biography. If necessary they could then apply for a Removal Order to send them there. A person could sometimes obtain their own Settlement Certificate as proof that their home parish, where they had settlement, would take them back if they became in need.

Here is a link to an article that explains the Poor Laws in more detail:

https://www.genguide.co.uk/source/settlement-certificates-examinations-and-removal-orders-parish-poor-law/

I believe the idea of settlement was also imported to the American colonies.

LikeLike

Excellent article once again, Judith! I will definitely check out the resources you have mentioned. Luckily for me my great, great grandfather’s occupation as a tailor enabled me to identify him as he moved from place to place in England, Ireland and even over to Canada with his very large family in the mid 1800’s. It amazes me that some of my other ancestors changed occupations so frequently.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank goodness he kept to tailoring. It was probably a very useful occupation too if you had a large family.

LikeLike

Thanks Jude for another really informative blog about our ancestors occupations. This is a really important subject and for me is a “bridging” topic, where you go from just looking at an ancestor’s BMD’s and timeline, to looking deeper into their life and how social, economic and historical factors influenced their life. occupation is probably one of the first topics that we tackle in detail and this blog goes a long way to help us understand the importance of why we need to study our ancestors occupations in depth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I couldn’t agree more! I think it is easy to become overly reliant on parish registers at earlier dates and as a result, we don’t look enough at other contemporary sources that can tell us much more about our ancestors. There is quite a range of records that provide information on occupations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love your Work! (pun intended)

Come and be a speaker at my December Genealogy Story Conversation?

We’d love to hear more about the occupations of our ancestors.

See my private messenger note!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Carole! I will reply to your message.

LikeLike

I have definitely used occupations to help me with my research and am fortunate that at least some of my ancestors had some distinctive occupations that, combined with other information in certain records, allows me to identify them. I love researching about the various occupations as well 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me too, learning about a particular occupation and what it involved can give you a real insight into an ancestor’s day to day life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am researching my own family and my ancestor, Reuben Franks, is the brother of yours. I’d love to find out any more that you know about them as I’ve got as far as his parents, William Franks and Mary Stone (b. c. 1731?) but can’t find any more about them from thereon. Im particularly interested in their origins as I am led to believe that the Franks/Francks were Jewish, possibly originally from the Czech Republic (but this is speculation). It’s great to find Reuben here though!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Tilly, Reuben Franks is indeed the brother of my ancestor Mary Franks. I know from an apprenticeship indenture that he was a tailor in Maidstone, where he lived with his wife, Jane, nee Fry and family.

I have never found a baptism for Reuben or Mary so I am not certain that their parents were William Franks and Mary Stone, though William may well have been a relative. However, there is a marriage in Wrotham St George for a Reuben Franks and a Sarah Jarrett in 1749. They might well be Reuben’s parents or at least an uncle and aunt, given the distinctive name. There is a burial in Wrotham for a Reuben Franks in 1762 and he is described as a husbandman (small farmer) of Kingsdown.

There are some clusters of Franks families in Kent at earlier dates and it is a name recorded in England in the Medieval period so I doubt there is a Jewish/Czech connection.

Have you taken a DNA test? It would be great to see if we are matches.

Best wishes,

Judith

LikeLike

Hi, thank you for the information you’ve got. I had the main bits about Reuben but it’s interesting to hear about the other Reubens. I know that “our” Reuben had a son called Reuben but he’s too late to be the ones you mention (1781-1862). No I haven’t taken a DNA test yet but intend to soon. Re the Jewish/Czech connection, my great grandmother (Mary Eliza Francks known as Polly) was Jewish, born to a Jewish family, but I’m absolutely unclear whether that is from her Mother’s line or her Father’s. I found a Reuben Francks with a brother named Horatio Francks (which fits with our Reuben, who had a brother with that name), and Horatio was living in Prague at that time (I very much wish I’d saved the details of the site I found it on as it was at the start of my research and I didn’t record everything as meticulously as I should have done), which I think was in the mid nineteenth century which fits. That, and the unusual name Reuben, made me suspect this was the Jewish connection and that the family may have originated there or had relatives there, but like I say, this is speculation on my part and there could have been all kinds of reasons for him to be there. If I do find out more I will post it here. Thanks again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Tilly, I would love to know more.

LikeLike