As many readers of my blog will know, I have long had a particular interest in the RAF, as my uncle, Gordon Herbert Batchelor, was a member of 54 Squadron during World War II. Another young man in my family, who saw service with the RAF, is my mother’s cousin, Sergeant David Nicholson Clough of 196 Squadron. Knowing comparatively little about him, I decided that it was time to put this right.

David Nicholson Clough was a lad from Coventry, a city in the West Midlands that was the home of many engineering industries. Given his subsequent career, young David may well have found a job in the aviation industry in the city, perhaps training as a fitter or a mechanic, for a company such as Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft. With the outbreak of the War in 1939, the city’s factories were running at full capacity producing aircraft, motorbikes, lorries, tank engines, submarine parts, and naval guns to satisfy demand from the military. Similarly, millions of artillery shells, fuses, bullets and grenades were produced in Coventry’s ammunition factories. Given its importance to the war effort, the city was targeted in a series of raids by the Luftwaffe and suffered great devastation in the Coventry Blitz. The worst raid was on the night of November 14/15 1940 when Coventry’s Medieval cathedral was burnt to a shell and most of the city centre was destroyed.

This is photograph H 5600 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums.

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3209283

David was certainly keen to serve his country, as it is known that he joined the RAF Voluntary Reserve, probably in 1940, when he turned 18. He was then selected to train as a flight engineer, a post introduced in 1941 with the advent of large complex bombers that had four engines. These huge aircraft needed a specialist onboard to be in charge of the operation of the aircraft and to assist the pilot. (Large bombers only had one pilot as it was considered wasteful to have two pilots because of their heavy losses.) The flight engineer was therefore expected to be able to fly the plane, straight and level on a course, if the pilot was out of action. His other duties can be described as follows:

The flight engineer controlled the aircraft’s mechanical, hydraulic, electrical and fuel systems. He also assisted the pilot with take-off and landing. In an emergency, the flight engineer would also be needed to give accurate fuel calculations. He was also the reserve bomb-aimer and helped to look out for enemy fighters. On the ground, he also liaised with the ground crew, who were responsible for servicing and maintaining the aircraft.

https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/whos-who-in-an-raf-bomber-crew

Flight engineers were initially selected from experienced ground crews, particularly fitters or flight mechanics, but from July 1942, suitably qualified civilians were also accepted for training. Flight engineer training was formalised in May 1942 with a series of courses set up at St Athan in South Wales. These including a three week course in gunnery, so flight engineers would be able to take charge of the turret or gun in the event of the gunner being killed or wounded. At first these courses lasted for seven weeks but they were then lengthened to twenty four weeks to accommodate entrants with more limited experience. By the end of the War, over 22,500 flight engineers had graduated from St Athan and an estimated 10,000 had died. All flight engineers were given the rank of sergeant so if they fell into enemy hands and became prisoners of war, they would receive reasonable treatment.

My research in the Operations Record Books (AIR 27) of Squadron 196 has revealed that Flight Engineer David Nicholson Clough joined the Squadron on August 5 1944, after being posted from 1665 H.C.U. (Heavy Conversion Unit). This unit was based at RAF Wolfox Lodge in Rutland, where men were training from medium bombers to heavy bombers. Accompanying him to 196 Squadron were his flying companions, F/O J.W. McOmie, (Pilot), F/O G.M. Cairns, (A/B – Air Bomber), F/O J.L. Paterson, (Navigator) and F/Sgt. R. Brooks, (W/Air – Wireless Operator) and F/O G.F. Talbot, (A/G – Air Gunner).

Squadron 196 was formed in September 1942 as a night bomber squadron. Between February to November 1943, it made many bombing trips to industrial centres and enemy ports, as well as some “gardening” mine-laying operations. In November 1943 the Squadron was transferred from Bomber Command to the Allied Expeditionary Force and after moving to various bases, settled in March 1944 in Keevil, Wiltshire as part of 38 Group, flying Short Stirling bombers. The Squadron’s role was to take part in top secret and dangerous “cloak and dagger” missions. These involved the hazardous job of towing engineless gliders to transport troops (gilder infantry) and dropping heavy supplies to the Resistance in Occupied Europe, as well as top secret drops of SOE (Special Operations Executive) parachutists on moonlit nights. Stirling aircraft were ideally suited to these missions, as they were powerful enough to tow and carry heavy weights. The aircraft’s low ceiling, (which meant they could only be flown at lower altitudes), made them suitable for accurate air drops.

In June 1944, 196 Squadron was in action as part of Operation Coup de Main, dropping parachutists of 5th Parachute Brigade, 6th Airborne Division so they could hold the bridges at Caen Canal and the crossing at the River Orne. Each Stirling carried twenty troops and their equipment. Further drops were made in June 1944 of supplies for the Allied forces involved in the invasion of Europe.

Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205127059

After continuing with their cloak and dagger missions, the next big assignment for 196 Squadron was Operation Market Garden, which took place from September 17-24th 1944. After the success of D-Day and the liberation of France, the Allies wanted to press their advantage so the Germans would not have the opportunity to regroup and increase in strength. Accordingly, a plan was devised by Field Marshal Montgomery to chase the occupying German forces back to the Dutch/German border. Operation Market Garden was to be the largest airborne operation in history: 34,600 British and American paratroopers of the 101st, 82nd and 1st Airborne Divisions and the Polish Brigade were to be flown over enemy territory and dropped around the Dutch towns of Eindhoven, Nijmegen and Arnhem. The objective of the paratroopers was to seize nine strategic bridges held by the Germans to create a salient (or bulge) into German territory. As there were not enough aircraft to drop such large numbers of troops all at once, they had to be dropped in stages over a number of days. The campaign began on September 17th 1944 with 1500 planes and 500 gliders.

Speed was essential, as the territory covered by the paratroopers was around sixty four miles in total and they had to hold out long enough for the Allied forces on the ground to reenforce and resupply them. At the same time, Allied artillery would pound German units, allowing Allied tanks to advance and providing air cover for the incoming planes. Once the bridges were secure, the Allies could enter the Rhineland and march on towards Berlin. From the start, it was recognised to be a risky operation but the rewards could be great: the War might be over by Christmas!

Paratroopers assemble near Mk.IV Stirlings of 620 Squadron during Operation Market Garden in September 1944

By Bridge B (Fg Off), Royal Air Force official photographer – This is photograph CL 1154 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1913225

Throughout Operation Market Garden, American and British bombers were dropping men and supplies over the Drop Zone (D.Z.). The RAF bombers were particularly involved in glider operations, bringing in vehicles, artillery and ammunition. Flights were made during the day time as it was against Allied airborne conventional wisdom to conduct big operations in the absence of light. By this time, the Allies had air superiority but there was still the danger of flak units on the ground, particularly around Arnhem.

On September 18th 1944, the crew of LJ846 took off from Keevil in Wiltshire at 11.50, David Nicholson Clough being part of a crew of six in his role as flight engineer (the crew had joined 196 Squadron together the previous month). Their mission was to re-supply Arnhem and they were one of twenty two Stirling bombers, towing Horsa gliders. The details of the flight were given as follows:

Market II. Arnhem. 1 Horsa. 1st A/B Division. Satisfactory trip.

Operations Record Books Air 27-1167 4 – 196 Squadron http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/

The Stirling touched down again at Wethersfield at 17.35, so had been airborne for nearly six hours. Fortunately, all the bombers had returned safely, despite the heavy anti-aircraft fire, and all but three gliders had been successfully detached.

The following day, September 19th, the same crew took off again in LJ846 at 12.10:

Market III. Arnhem 1st A/B Division. Unsuccessful. Mission abandoned due to eng. seizure. Glider cast off at CO. 39 W 51 38 N/

Operations Record Books Air 27-1167 4 – 196 Squadron

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/

The operation was short-lived due to engine failure and after casting off the glider, the bomber returned to base at 13.40.

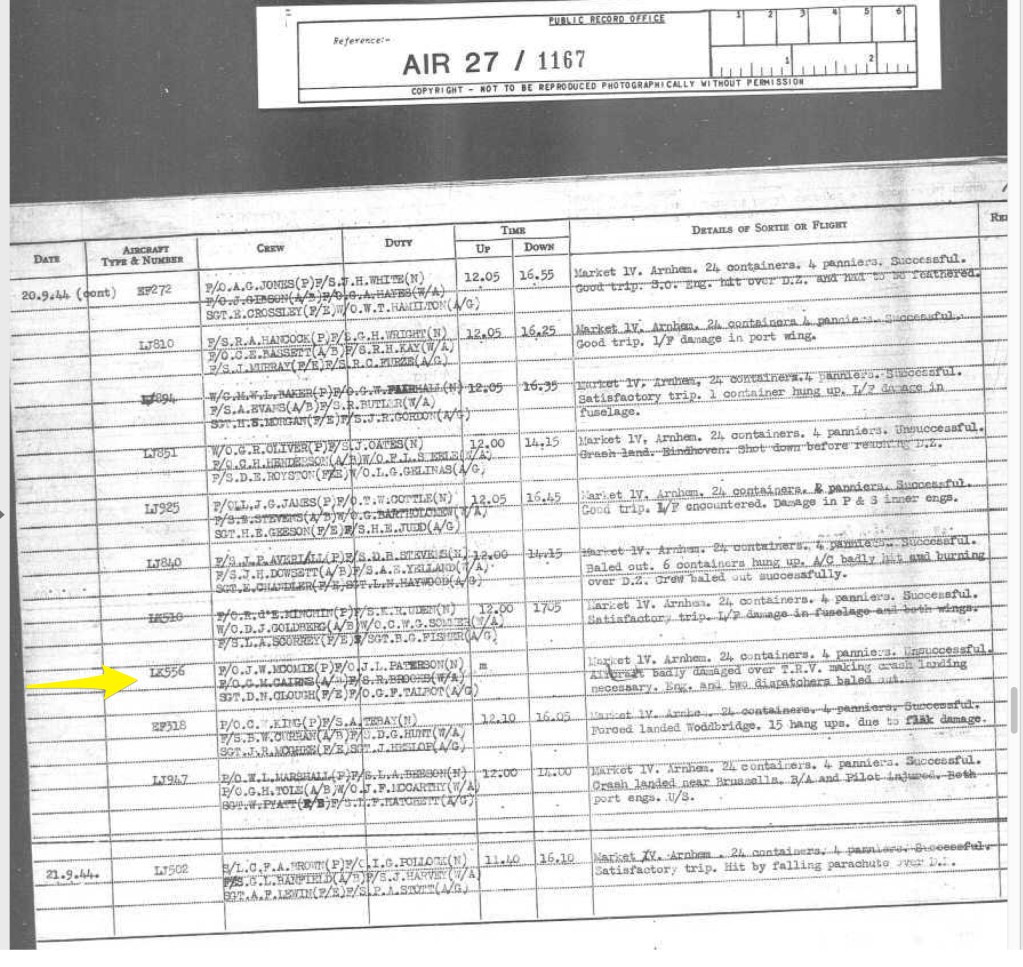

On Friday, September 20th, the crew transferred to LK556 and took off around midday on a mission to re-supply Arnhem:

Market IV. Arnhem. 24 containers, 4 panniers. Unsuccessful. Aircraft badly damaged over T.R.V. making crash landing necessary. Eng. and two dispatchers baled out.

Operations Record Books Air 27-1167 4 – 196 Squadron http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/

Sergeant David Nicholson Clough, the Flight Engineer on board this ill-fated flight, baled out along with two despatchers from the Army, whose job it was to unload the supplies. Out of the seventeen Stirling bombers of 196 Squadron that had taken off that day, only ten made it back. It was described as an “expensive” day for the Squadron both in crew and aircraft. Flak from the anti-aircraft batteries had been very intense and with great bravery, the Stirlings had dropped to the lowest possible altitude to ensure their drops could be made with accuracy. Whilst they were waiting for their turn, circling overhead, they were easy targets for flak and witnessed other aircraft around them catching fire.

According to the family story, with the aircraft sustaining terrible damage, an order was given for the crew to bale out. David Nicholson Clough was the only one to bail out before the order was rescinded and the other crew members had all survived. However, the Operations Record Books (ORB) of 196 Squadron have revealed that the two Army despatchers also baled out with him. Sadly, they too fell to their deaths, undoubtedly because the low altitude of the aircraft meant there was insufficient time for their parachutes to open.

Sadly, many things about Operation Market Garden did not go to plan, though the Allies succeeded in liberating the Dutch towns of Eindhoven and Nijmegen from the Germans. The narrow roads in the area and lack of communication between the paratroopers and the ground forces, due to faulty radios, slowed the progress of the Allied forces. Poor planning, tactical mistakes and bad weather also worked against them. The British troops of 1st Airborne Division, supported by men from the Glider Pilot Regiment and the Polish Parachute Brigade, had been able to liberate the town of Arnhem but soon became trapped and outnumbered. The men were only supposed to hold the bridge at Arnhem for two days but in the event, they held it bravely for twice as long whilst German units pummelled the town, torching buildings where the men were hiding. Only 2000 of the original 10000 paratroopers of the 1st Airborne Division came back alive and the goal of securing a bridgehead over the River Rhine and a foothold into Germany was not to be realised.

Family members were told that a Dutch couple, a farmer and his wife, found the body of David Nicholson Clough on their land. Rather than let him fall into German hands, they decided to secretly bury his body in their orchard. It was only after the War, when they were able to go to the relevant authorities that his resting place was discovered. He was then reinterred in Jonkerbos War Cemetery in the Netherlands.

https://www.cwgc.org/visit-us/find-cemeteries-memorials/cemetery-details/2062100/jonkerbos-war-cemetery/

Further information on David Nicholson Clough can be found on the CWGC website. It confirms that although he had died on 20 September 1944, he was not buried in the cemetery until 14 April 1947, some time after the War had ended, and had previously been buried elsewhere:

His grave has this inscription:

From sky to earth for liberty I fell, I fought, I won my wings again, farewell

https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2645261/clough,-david-nicholson/

On the same date, in a neighbouring plot was buried Warrant Officer, James Joseph Hyde of 132 Squadron who had died on September 25th 1944:

The previous location of the grave of David Nicholson Clough is given as a map reference, perhaps the location of the farm where had landed. Nijmegen was on the frontline until February 1945 and many Dutch civilians had been forcibly moved from the area by the Germans. A temporary war cemetery had also been established at Jonkers Bosch nearby.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WaN91_NGJoI1067

What was the fate of the two air despatchers that had baled out with their flight engineer? A Dutch Airwar Study Group has researched the fate of the occupants of LK556 on September 20th and has identified the air despatchers as follows:

| Air Despatcher | Drv. | R.F. | Pragnell | T/61437 | RASC | Groesbeek Memorial | Maybe buried as Unknown at Heteren | ||

| Air Despatcher | Cpl. | A.W.J. | Pescodd | T/47580 | RASC | Jonkerbos | 4 E 4 |

https://verliesregister.studiegroepluchtoorlog.nl/rs.php?aircraft=&sglo=T4211&date=&location=&pn=&unit=&name=&cemetry=&airforce=&target=&area=&airfield=

Corporal Alfred William James Pescodd was 38 years old and a member of the Royal Army Service Corps, 63 (Airborne) Div. Comp. Coy. He was buried at Jonkerbos Cemetery on May 21st 1947. The whereabouts of Driver Robert Frank Pragnell (of the same unit as Pescodd), and aged 39, is unknown, though the Dutch Air War Study Group suspect that he may be one of the unknown airmen buried at Heteren. He is remembered on the Groesbeek Memorial, Panel 9. Further information on these two air despatchers can be found on the website of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission: https://www.cwgc.org/.

There is also the question of what happened to the other crew members of LK556 who survived. According to the Dutch Study Group, the aircraft crashed at Valburgseweg Elst – Lienden on September 20th. Their Squadron, back at Keevil, did not know what had happened to the crew until a few days later:

25.9.44. Today heard first news of P/O McOmie (who was missing on 20.9.44.) through the medium of the Daily Telegraph, in a story from one of their correspondents. “I was 4 Days behind the German Lines”.

Operations Record Books 196 Squadron – AIR 27-1167-5 – http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/

I haven’t been able to track down a copy of this newspaper article but the journalist can be identified as Edmund Townshend a war correspondent of The Daily Telegraph attached to 190 Squadron, 38 Group. The story of how he was shot down over Arnhem (on his first flight) and his encounter with the airmen of LK556 appears in his obituary, which was published in the Daily Telegraph on November 28th 2008 and has been produced on the Pegasus Archive, an archive of the British Airborne Forces 1940-1945:

“The Stirling bomber, No 190 Squadron’s R for Roger, had just dropped its supplies to troops on the ground amid heavy flak, and Teddy Townshend was watching from the co-pilot’s seat the coloured parachutes floating down like autumn leaves when he heard over the intercom: “Weave, skipper, weave… Keep weaving.”

“Engineer officer,” called the pilot, “come forward and take a look at the port outer motor on fire.”

“What port outer motor on fire?” asked the engineer officer.

“Bail out,” came the order and, after clipping on his parachute, Townshend found himself being bundled to the open hatch in the nose.

Gripping the parachute release handle to make sure I had it, I leapt into space too eager to escape from the blazing plane to feel fear at the drop,” he wrote in his front page story. “For minutes like hours, dreading attack by machine-gunners below, I swayed slowly to earth. Breathlessly I watched the Stirling roar away in flames, losing height. With relief I saw other parachutes opening in its wake.

On landing in a ploughed field south of the Rhine, he was immediately met by members of the Dutch underground who gave him food and drink, and buried his parachute and Mae West. They were disappointed that he carried nothing more dangerous than a pencil and notebook, but escorted him along dykes and behind hedges to meet up with nine fliers, including the crew of R for Roger, whom they made lie down in a beech wood in silence for fear of enemy patrols.

At dawn the underground returned with hot milk and sandwiches. German ack-ack fire whistled through the tops of the trees as another supply flight passed overhead in the afternoon, and the group ended the day crouching in a tunnel as the artillery of both sides exchanged shells. Setting out at dusk with a map, compass and hard rations they found the roads too dangerous and the dykes too wide and deep to cross. They encountered their first Allied patrol the next morning.

A farmer’s family invited all of them into their house, where Flying Officer Tom Oliver of R for Roger sat down at the harmonium to play the Dutch national anthem, and a picture of Queen Wilhelmina was pinned on the wall. A dozen more fleeing airmen appeared – one had landed in the river and swum 100 yards to the Dutch side as the Germans fired at the floating body of his co-pilot; others had watched the enemy retreating without shoes, one man furiously pedalling a child’s bicycle. Eventually the group, which possessed a total of three pistols between them, started to stroll across an open field; but sniper-fire drove them to take shelter in a ditch before they were taken to a tactical headquarters, from where Townshend hitched a lift to Brussels to phone over his story.

When he submitted his expenses back in London they included “replacement of splinter-proof spectacles swept away by an involuntary parachute exit” and “rewards to Dutch underground workers for protection from enemy search parties”. The news editor paid up with a wry grin.

https://www.pegasusarchive.org/arnhem/edmund_townshend.htm

There is also a first-hand account of what happened from one of the survivors of the crash of LK566, Flying Officer George Murray Cairns, the Air Bomber, in his M. I. 9 Evasion Report, (compiled by the War Office), again published by the Pegasus Archive. He wrote the following:

We left Keevil on 20 Sep 44 in a Stirling aircraft to drop supplies on Arnhem, but were shot down by Flak before reaching our zone. We jettisoned our supplies and crash-landed South-west of Elst (N.W. Europe, 1:250,000, Sheet 2a, E 77). Immediately on landing some Dutch peasants surrounded us, told us that there were Germans all round, and that we should go North with a view to crossing the river and joining up with the airborne troops in Arnhem. A member of the underground led us to a small wood, where we stayed overnight. In the morning (21 Sep) the man returned, bringing with him the crew of another Stirling that had been shot down, together with a reporter from the “Daily Telegraph”. He also told us that it was impossible to get across the river, and advised us to stay where we were.

We stayed there all day, and the next morning (22 Sep) a priest told us that there were some British troops on a road close by. We went out to the road, and met a British recce convoy, but they were pushing forward and advised us to wait for the British troops that were expected in two hours. They informed the British headquarters by radio where we were. The troops did not come, so we went back into hiding and made contact with a farmer, who fed us and promised to keep us informed.

The following day (23 Sep) the farmer told us that the British troops were in Valburg (E 66), so we walked back and reported to their headquarters. From there we hitch-hiked to Brussels, arriving on 25 Sep.

I was in hospital in Brussels until 4 Oct, when I was flown to England.

https://www.pegasusarchive.org/arnhem/george_murray_cairns.htm

Cairns also reported that the fate of Clough and the two Army personnel was unknown. I wonder how long it was until their families knew that they were dead.

Altogether, 196 Squadron carried out 112 sorties during Operation Market Garden: half involved glider towing, the other half were resupply flights. Ten aircraft were lost and many were badly damaged. Twenty six members of the crews were killed, as were eight RASC dispatchers, with two members of the Squadron taken prisoner. Thirty three crew members, who had successfully bailed out over Arnhem, were able to make it to the safety of the Allied lines when the 1st Airborne Division withdrew across the River Rhine on the night of September 25/26th.

It seems terribly unlucky that David Nicholson Clough, and the two Army despatchers with him, did not survive their mission, though one is thankful that the other crew members, who remained with the doomed aircraft, survived its crash. However, I am happy to know more about his role with 196 Squadron and am proud of his contribution, amongst those of so many others, in freeing occupied Europe from Nazi oppression.

@ Judith Batchelor 2022

N.B. The Operations Record Books have recently been indexed on The Genealogist website http://www/thegenealogist.co.uk. These should reveal when David Nicholson Clough began his service with the RAF and where he was prior to joining 196 Squadron in August 1944. His service record, held by the Ministry of Defence, would also provide personal details and additional information on his career and training as a flight engineer.

Please click on the links below if you would like to read more about 54 Squadron during the Battle of Britain and the Red Cross prisoner of war records:

Incredible piece of research Jude, so much information and details, sad that three of the crew did not make it home, but by telling their story you have ensured that their memory lives on forever

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you! I didn’t know a lot about Operation Market Garden previously but the research makes you realise how many heroically played their part in liberating Europe. There were the crews of the aircraft, the paratroopers, the despatchers, the Army troops on the ground, the SOE, the Resistance and ordinary Dutch civilians, all bravely seeking freedom from oppression.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very moving story of dedicated, courageous men. So glad you were able to share so many key details about who they were and what they did during the war.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It is really humbling to read their stories. Ordinary Dutch civilians also risked their lives to help stranded airman get back to safety.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My mum’s uncle was on the ground at Arnhem. This has given me a better understanding of the objectives of Market Garden. The proportion of flight engineers from Athan who lost their lives is really shocking. Through the first-hand accounts of men in parallel situations, we can feel their breathlessness as they jump from a burning plane into thin air, trusting in the parachute to save their lives.

(I’ve also learned what a Mae West life preserver was, and the meaning of flak.)

LikeLike

My mum’s uncle was on the ground at Arnhem. This has given me a better understanding of the objectives of Market Garden. The proportion of flight engineers from Athan who lost their lives is really shocking. Through the first-hand accounts of men in parallel situations, we can feel their breathlessness as they jump from a burning plane into thin air, trusting in the parachute to save their lives.

(I’ve also learned what a Mae West life preserver was, and the meaning of flak.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I confess that I had to do a lot of reading up on Arnhem (and flight engineers too) but you come away in awe of the men’s courage and determination. It is hard to imagine baling out praying that your parachute will open, and none too sure whose hands you will fall into if you do reach the ground. Some men were also shot at whilst they were falling so it was incredibly dangerous. Like you, I am slowing building up a dictionary of relevant words and terms associated with WW2.

LikeLike