Wills are truly the most wonderful source for family history. They provide unparalleled evidence on relationships, enabling extensive family trees to be constructed. Wills may also lead to you other sources, such as title deeds or manorial records, due to the description of land holdings. They also help you to pinpoint relevant baptisms, marriages and burials and supply valuable details about a person’s occupation and residence. What I love most of all is that through wills, you can discover who was the testator’s nearest and dearest and how they wanted their personal possessions and real estate to be distributed after their death. Nevertheless, many family historians ignore this important record source, believing, erroneously, that their family will never feature in them because they were just ordinary folk. Only rich people will be found in wills! The purpose of this article is to make you think again.

You may be convinced that probate records are not of interest to you because you have yet to find any for the family you are tracing. My recommendation is that instead of just searching by a name, you should try searching by place. This is because generally, probate records are only indexed by the name of the testator, or the name of the deceased if they did not make a will and an administration was produced instead. Within the records are many more names: the names of the beneficiaries, executors, administrators and witnesses, any of whom might be your ancestor. However, you will never find them unless you look at the actual documents. It is amazing what connections you can find, especially if your ancestors lived in a small village, where there was a lot of intermarriage between local families. An added bonus is that you might find records of interest that you have overlooked previously under a name search because of unexpected name variants. At the same time, you gain a real insight into the lives of the local inhabitants, your ancestors’ friends and neighbours.

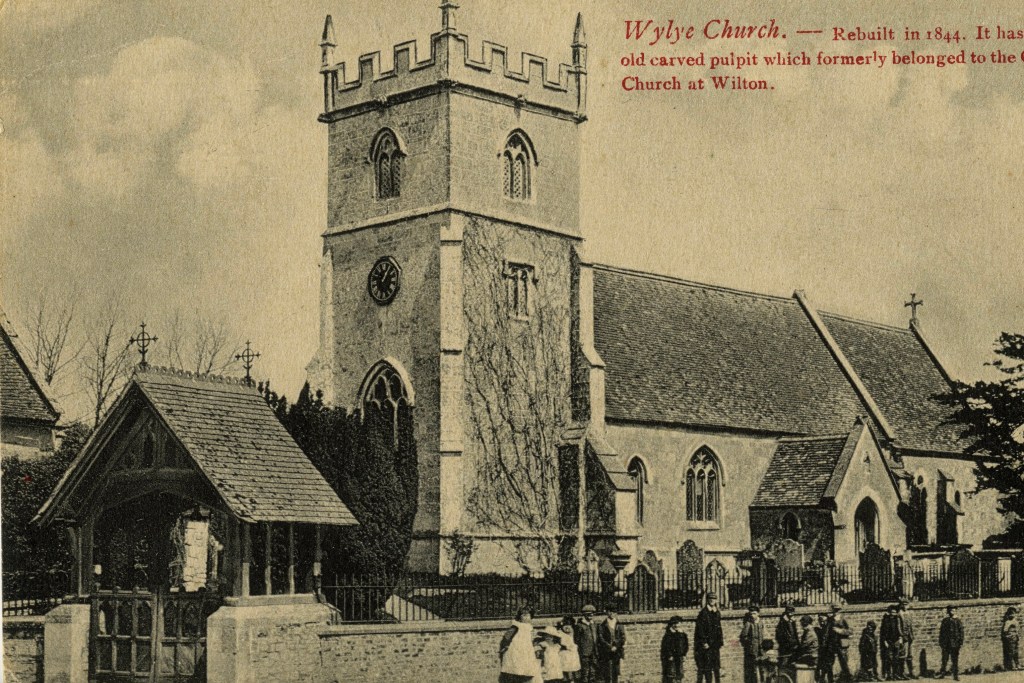

The small village of Wylye in Wiltshire is a place close to my heart, as it was the place of birth of my grandmother in 1897. It is situated between the towns of Salisbury and Warminster, Wiltshire, in the Wylye valley, along the river that gave the village its name. Wylye, historically usually spelt Wiley, was a farming community, with sheep pasture on the downs above the village and wheat, oats and barley being the principal crops grown in the valley. Philip Bennett, my fourth great grandfather, was born there in 1783, the fifth child and second son of Philip Bennett, a labourer, and his wife, Sarah, nee Small. On the surface, given Philip’s occupation, it might seem unlikely that I would find any probate records of interest. Wylye’s yeoman farmers and tradespeople with some assets would be the most likely people to make wills. Would a humble labourer or his antecedents feature in them? In fact, I found at least three wills made by labourers of Wylye. It should also be remembered that children did not necessarily receive an equal inheritance, or fortunes were lost. Earlier generations of your family may have been richer even if wealth was not passed down through your own particular branch.

The proving of wills was in the hands of the Church until 1858. This article is not primarily about the complex arrangements of the different ecclesiastical courts but suffice to say that finding wills prior to 1858 can be challenging, as different courts had jurisdiction over particular parishes. In addition, the services of a superior court could be used and would be required if property fell in more than one jurisdiction or during a bishop’s visitation, when the lower court was “inhibited”. Nevertheless, Wylye comes under the jurisdiction of the Archdeaconry of Sarum and most Wylye testators had their wills proved by this court, though a few, chose or needed to use the services of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, the highest court in the land. Fortunately, probate records from the various local courts in Wiltshire have now been indexed by Wiltshire and Swindon Archives. The actual records are available to view online at Ancestry (http://www.ancestry.co.uk) and it is possible to search them by place, rather than by name. In this article I will illustrate why probate records are essential for family history research, using some real examples from Wylye.

Firstly, it is necessary to search Ancestry’s Card Catalogue to find the collection, Wiltshire, England, Wills and Probate, 1530-1858. Ancestry has other big probate collections too for Yorkshire, Wales, London and the Diocese of Lichfield and Coventry. To set some parameters for my search, I decided to look at probate records between 1700 and 1858 for Wylye. I found eighty six records altogether for this time period. Unfortunately, though they were all described as wills, I found that many were in fact administrations, where permission to administer the estate of the deceased was sought from the court because the person had died intestate. Administrations are not as useful genealogically as wills. There was also a smattering of inventories. Using an Excel spreadsheet, I put together a table listing the name of the deceased, the date of the record and any notes on the contents. The fact that the records are online made this a straightforward task.

In general, most of the records were simple to read and followed a similar format. The earlier wills usually had a lengthy preamble in which the testator committed themselves to God’s mercy and requested that their executors ensured they were decently buried. Bequests were then made and the will is dated, signed and witnessed. Fortunately, they were not full of the legalese that one tends to find with wills proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury. The date the will was made is very important. Any information that the will contains relates to the date it was written, rather than the date it was proved. It is clear though that wills must have often been written on death beds, as frequently, they were proved shortly afterwards. I even found one nuncupative will, a will that was spoken and written down by witnesses who testified that they had recorded the testator’s true wishes. The authenticity of a will was important and occasionally, witnesses had to appear before the court to swear an oath to the will’s veracity. Testators often said that they were revoking any former wills and if it was a long document, they noted down the number of pages to ensure compliance with their final wishes.

The role of executors was very important. Often, husbands would appoint their spouse or children for the role but my examination of the wills of Wylye suggests that friends were frequently given the task, particularly if minors were involved. In certain circumstances, it would also have been advantageous to have someone who was neutral and outside of the immediate family, as inevitably, some bequests must have been contentious. Typically, land and the profits from its rental would either be given to the widow, and not sold or divided up until after her death, or sold immediately, with the interest invested from its sale to be used to support her until her death or remarriage. Similarly, if the beneficiaries were under twenty one, the age of consent, interest on real estate would often be used for their maintenance and even education until they came of age and could inherit the land holding in their own right. Minors feature often, as parents needed to make provision for their dependant children. Similarly, grandparents often remembered their grandchildren in their wills, especially if the latter had suffered the loss of a parent.

Building a family tree

Two Wylye wills of particular interest to me were the wills of Thomas Small, proved in 1794, and Lydia Small, proved in 1805, the parents of my ancestor, Sarah Small. The wills produced the following family tree:

From his will, I learnt that Thomas Small was a baker, something that had not been recorded in parish registers. He left £100 each to his three sons, Henry, William and Edward, to be paid to them immediately after the death of his wife, Lydia. However, his three daughters, all identified with the names of their husbands, were to receive only one guinea each “and no more”, paid within a month of his decease. His wife, Lydia, was to receive everything else, including the “stock and utensils in the bakery business”. It is likely that Thomas and Lydia had run the business together so she would carry on after Thomas’ death. The daughters’ bequest of one guinea each was a tiny fraction of the money their brothers received. At first sight, it appeared that my ancestor, Sarah, the wife of the labourer, Philip Bennett, had been harshly treated. However, perhaps Thomas and Lydia had agreed to make provision for their daughters after Lydia’s death. In her will that she wrote in 1795, Lydia requested that her executor, John Perrior of Wylye, should sell her land, and all her possessions after her death with the exception of her clothes, and invest the proceeds for the benefit of her three daughters. Once again, the names of her daughters’ husbands are given, this time with the addition of their occupations. Interestingly, Ann Small, Lydia’s granddaughter, who was living with her, was to receive a bequest of £20 and a share of her clothes. None of Lydia’s sons had a daughter named Ann at this time, which suggests that Lydia’s granddaughter may have been illegitimate. Lydia had a daughter named Ann who had died eight days before her father had made his will, which explains why she is not mentioned. In nearby Tisbury, there is the baptism of Anna Maria Small, the daughter of Ann Small on 14 December 1775. It looks likely that Anna Maria was Lydia’s granddaughter and Lydia had taken her in to live with her.

Female Ancestors

Around twenty percent of wills in Wylye for this period were made by women, mainly widows, and these are often the most interesting wills of all because of the numerous bequests to family and friends. As a result of changes in name and brides moving away from their family home, women can be particularly difficult to trace. However, women frequently feature as beneficiaries in wills, as well as acting as witnesses and executrixes. Probate records can therefore be especially useful in identifying women, who may have changed their name several times if they married more than once. This is illustrated by the will of Robert Small, a cousin of Sarah Small. A gentleman of Wylye, Robert Small wrote his will in 1813 and made his “dear mother, Frances Patient” and his brother, William Small, the beneficiaries of his estate. The parish registers of Wylye record the marriage of Frances Small, a widow, to George Patient, a widower and gentleman on 22 February 1797. A few years earlier, Frances Gibbs married Robert Small by licence on 28 April 1790 in Wylye. The will provides the evidence that Frances Gibbs, Frances Small and Frances Patient are actually the same person.

The will of Ann Brandis dated 1806, turned out to very useful to my Small research. In Ann’s will, she gives a mourning ring that was made to commemorate her brother, William Small, to her granddaughter Diana Brandis. The burial of William Small is recorded in the Wylye burial registers in 1788. Apart from revealing the provenance of a family heirloom and treasure, this bequest provided the evidence of Ann’s maiden name. She left several bequests to the following individuals:

- Her son, Thomas Hinwood, a carrier of Symmington

- Her daughter, Ann Rumsey

- Her granddaughters, Henrietta and Sophia Scammel

- Her granddaughter, Diana Brandis

- Her son, Christopher Brandis

It took some investigation to untangle her various marriages. It turned out that Ann Small was the sister of my ancestor, Thomas Small. She was baptised in Wylye on November 16 1731. In 1756, she married her first husband, Thomas Hinwood. Sadly, she was left as a widow with three young children upon his death in 1765. Two years later, in 1767, she married a 46 year old bachelor, Richard Rumsey, and they had two daughters before his death in 1771. She married for a third time in October 1773, her new spouse being Christopher Brandis. The marriage was very short-lived as Christopher dies in August the following year, leaving Ann pregnant with their son, who she names after his father at his birth in February 1775.

Looking at the Wylye probate records, I can see that when Ann’s first husband, Thomas Hinwood died, Ann applied to administer his estate as Thomas didn’t leave a will. She was assisted by William Small, a corn miller of Wylye (her brother) and Thomas Fricker, a dairyman of New Court, Downton, (a relative on her mother’s side). Her second husband, Richard Rumsey left a will, made shortly before his death in 1771, and Ann is made the executor and her brother, Thomas Small, is a witness. Her third husband, Christopher Brandis, does not make a will and an administration was not produced. Without the knowledge of her previous names, (provided by the bequests in her will), I would not have been able to identify Ann in any of these prior probate documents. Likewise, I would never have known that any of them were relevant to my research if I had searched only by name. Sometimes a potential clue to a person’s identity may be found in the names of witnesses and administrators who might have been family members.

Parish Registers

Probate records can be very helpful in identifying baptisms, marriages and burials of family members. It is usually possible to find the burial of the testator, as most wills were proved within a few months of death and the date of their will tells you when they were last alive. However, parish registers have not always survived, especially at early dates, and some entries are missing.

The mother of my ancestor, Thomas Small, (whose will was proved in 1790), was Bridget Fricker. Bridget had been baptised in nearby Steeple Langford in 1697, the daughter of Edward Fricker and his wife Ann. The will of Thomas Fricker of Wylye, which was proved in 1737, proved to be very useful and produced the following family tree:

Thomas Fricker, the testator, can be identified as the brother of Bridget’s father, Edward Fricker. I already had the baptism of Edward’s son, Stephen, who was mentioned in the will, but most significantly, Thomas gives the mill at Wylye and land at Stockton to William Small, his kinsman. William Small was the husband of Bridget. Their eldest son, William, received Thomas’ household goods. What is especially significant about this will is that the other siblings of Thomas Fricker, who all received bequests, were unknown to me. Edward had been baptised in 1667 in Wylye, the son of Edward and Catherine Fricker but it would seem that records of the baptisms of Ambrose, Henry, Thomas, John, Bridget and Margaret, the other children of the couple, have probably not survived.

Migration

One of the most difficult problems a family historian faces is finding the place where a person originated. Even prior to the Industrial Revolution, people moved around the country, perhaps to find work or to join other family members. Even if a possible candidate is found, how can you prove that it is the person you are seeking? Wills can reveal those family connections to places.

An example of this is contained in the will of Mary Perrior, a widow of Wylye, who made her will on 8 December 1796. She names the following relatives:

- Her daughter, Sarah, the wife of James Coombes of West Stower, Dorset, yeoman

- Her granddaughter, Sarah Thorne

- Her granddaughters, Mary and Diana Mussell

From Mary Perrior’s will, we know that her, daughter, Sarah, had moved away to Dorset after her marriage. Sarah probably did not survive long enough to be recorded in census records, so this document provides valuable evidence about her parentage. If you have a potential baptism for an ancestor but lack the evidence that it relates to the person you are seeking, look at local probate records for proof.

Family Relationships

I love the fact that wills can give you an insight into family relationships. Isaac Fleming in his will dated 1819, gives his daughter, Anna Fleming, his household goods and furniture up to the value of £20, to be selected by his wife within a month of his decease. However, the following suggests that he did not trust his wife entirely to comply with this:

“But if my wife shall refuse or neglect so to do within that period of time, then the same shall be immediately afterwards selected by my Trustees hereinafter named”.

The will of Richard Rumsey, dated 1771 suggests that not everyone in his family approved of his late marriage, as a 46 year old bachelor, to Ann Hinwood, nee Small. He reserves his two granaries and the pump and cistern standing in the malt house for his wife:

“And in case the children of my said brother William make any demand of my wife, except for the household goods, I empower her to demand of them what they owe me for board and cloaths”.

Paternity

A big challenge in family history is the unknown paternity of illegitimate children. However, it is possible that the father of an illegitimate child might mention them in their will. If you do not know their name, you may only discover this by looking at wills for a particular place in the relevant time period. The will of John Neal, an innkeeper of Wily, dated 1805, made interesting reading:

“First I bequeath unto Mary Bryant daughter of Jane Bryant in the parish of Wily in the County of Wilts the sum of fifty pounds of lawful money of Great Britain immediately after my decease. I will the money be paid into the hands of William Thompson to put out the Money to Interest upon as good Security as he can and to pay unto the said Mary Bryant two shillings a week paid from the interest and when this is gone, from the whole.

John Neal also asks his executors to put Mary in school when she is old enough to learn, and to pay for her schooling “until that time she is proved to be a good scholar”. Mary’s mother, Jane, is to receive £10, £5 at the time of his decease and £5 twelve months later. A search of the Wylye parish registers reveals the baptism of Mary in 1798:

Ancestry.com. Wiltshire, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538-1812

Wiltshire Church of England Parish Registers, Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre, Chippenham, Wiltshire, England.

Clearly, though he does not identify her directly, John Neal wanted to make sure that his daughter, Mary, was taken care of. Money is even to be spent on her education after his decease. He is also well-disposed towards Mary’s mother, Jane Bryant, leaving her a bequest too.

Friends

It is also evident that friends were important and were often left legacies or trusted to act as witnesses, administrators and executors. I discovered that William Small, who was described as a miller of Wylye, (his father, William, had inherited the mill from Thomas Fricker), was appointed as an executor to his friend, John Abrey, a yeoman, in 1787, along with another friend, Charles Hibberd of Barford, miller. Much of John Abrey’s estate was to be held in trust for the benefit of Charles Hibberd the younger, the second son of Charles senior, for his education and maintenance until he was to receive the land at the age of 21. If Charles Hibberd was your ancestor, you may never know about his stroke of good fortune without looking at this Wylye will.

Personal Possessions

An inventory would be drawn up after death so the personal effects of the deceased could be distributed. Where these survive, they make fascinating reading, as one gets an insight into the contents of a person’s house. If they were farmers, their livestock and animals would also be included. Personal possessions could also sometimes be recorded as separate bequests in a will. Widows and spinsters were particularly keen to give specific items to their female relatives and friends. One will which I particularly enjoyed reading was the will of Ann Hayter, widow, dated 4 Nov 1763. She left all sorts of personal bequests, including the following:

- Daughter in law Jane Stone, widow of the late James Stone of Bulbridge Farm, Wilton, £5, three silk gowns, black velvet cardinal and my red quilted petticoat.

- Hannah Hayter, a widow, of Wylye, four guineas and the rest of her apparel to be shared equally with Miah Seawell, the wife of John Seawell.

- Mrs Jane Smith, two gold rings, one with this motto “In thee my choice I do rejoice”, the other a mourning ring in memory of John Stokes.

Trade/Occupation

You may find out more about a person’s trade through an inventory, which might list tools, or as a result of bequests made in a will. Christopher Card, who made his will in 1728, was a maltster. His daughter, Martha, was to receive one furnace, one kiln for making malt, one cistern, one granary house and one shovel house belonging to the messuage and tenement where he lived. His other daughter, Mary was to receive “three score pounds” when she reached the age of 21 and one brewing kettle. Martha was to take over her father’s malting business after her mother’s death.

Servants

I get the impression that many testators became fond of their servants, particularly if they had given them long service. Close relationships must have been formed, especially if they lived in and the testator was elderly and needed care. If your ancestor was a servant, it is possible you will find them mentioned in the will of their master or mistress. Nicholas Burt, a labourer, in his will of 1811, left £5 to Mary Perrier, his housekeeper, along with:

“one cheese and half a flitch of bacon if I do not Iive to spend it”.

John Mussell, a yeoman, granted his estate in 1757 to his two cousins and his servant, Martha Hinton, spinster, to be equally divided between them “share and share a like”

John Aubrey in his will of 1787, said that his servant, Ann Young, was to receive three guineas and the maidservant of Ann Hayter, at time of her decease, was to receive a wardrobe of clothing: her mistresses’ two best linen gowns, two white quilted petticoats, two best white aprons and two best blue-checked ones.

Care of Minors/Vulnerable Family Members

Filed along with the probate documents was a bond of guardianship, dated 5 December 1752 that referred to the guardianship of Thomas Small, aged 18, son of the late William Small of Wylye. This document therefore provided my ancestor’s age, the name of his father and the information that his father had died by this date. Matthew Pritchard, a shopkeeper of Tisbury, James Polder a miller of Tisbury, James Tebeult of the City of Sarum, innholder and Thomas Dunbare, a weaver, also of Sarum, were appointed as his guardians on 5 Dec 1752. I found that there was an administration for Thomas’s father, William, after William’s death in 1738. Perhaps because his father had died intestate, it was necessary to protect his estate and ensure that Thomas received his inheritance when he turned 21. Thomas had married his wife, Lydia Fry, two years earlier in 1750 when he was around sixteen years old, so perhaps his marriage had brought about the bond of guardianship.

It is highly unusual to find a will made by a married woman prior to 1882, because before this date, the property of a married woman belonged to her husband and a wife could only make a will with the permission of her husband. This was granted to Betty Locke, who is described as the wife of Richard Locke in her will dated 18 April 1791. Betty was very concerned about the welfare of her “unfortunate” son, William Warne, by her former husband, Matthew Warne. William was due to receive £300 when he reached the age of 21 but because of his “misfortune” it had never been given to him. Betty appoints executors to invest the £300 and asks that her son is put under their care and custody with the interest used to support and maintain him “until such time as it may please almighty god to restore him his mental faculties”. In her lengthy will she refers to various indentures made between her and other individuals along with a marriage settlement.

Marriage Settlements

Probate records provide evidence of marriage settlements. John Andrews, in his will dated 1828, states that his daughter, Katherine, had been advanced £400 as a marriage portion, (dowry) when she recently married Robert Gooden, a maltster of Collingbourne Kingston. He remarks tartly that if Katherine doesn’t return it so it is part of his estate, she will receive nothing more.

ADMINISTRATIONs

Generally, administrations provide limited information, perhaps the name of the surviving spouse or a child, along with the names of those appointed by the court to help administer the estate. However, occasionally, more information can be gleaned. For example, an administration was produced for Edward Davis of Wylye in 1784. Edward’s father, James Davis of Teffont Magna, was his next of kin but he renounced his right of administration. Edward’s children, who were all minors, were named as Elizabeth, Letitia, James, Edward and Mary Davis. Sometimes an administration was produced because the will of the testator was deemed to be invalid. In this scenario, the original will would be annexed. Commonly, this occurred because an executor had died.

William Bennett, the father of my ancestor Philip Bennett, died intestate in 1791. Philip was appointed to administer his father’s estate and this helped me to identify William’s burial in the Wylye parish registers. There was another burial of a William Bennett in 1781, and no ages were recorded in either entry.

PLace of Burial

Many testators requested that their executors should ensure that they were decently buried. Ann Hayter, in her will of 1763, wanted to be buried in the chancel of Wylye church, next to her husband. As a result, she gave the following bequests:

- One guinea to the Minster of Wylye for his consent to have her grave made in the chancel and another one for preaching a funeral sermon.

- One guinea to the clerk for digging her grave somewhat deeper than ordinary and for tolling the bell.

- One guinea to Joseph Lane, stone-cutter of Tisbury, for filling up the tombstone

- One guinea to John Doughty of Wylye for assisting at the funeral and carrying the brick to the church for the grave.

This will illustrates that you never know in what context an ancestor might be mentioned.

Charity

It is not unusual to find charitable bequests given by the wealthier members of the community. John Stevens, whose will was proved in 1701, gave £5 to be distributed to sixteen poor families the day after his burial.

Family Groups

Sometimes a will will mention who lived with the testator. John Barnett, in his will of 1742, gives bequests to his sister in law, Mary Cooper, and Jane Everly, spinsters, who lived with him in his house.

Religious Beliefs

It may be possible to discern if an ancestor was a non-conformist. Christopher Brandis, in his will of 1853, wrote the following:

“its my desire that the Chapel be always let to the same society for preaching as Long as my wife shall live”.

Ownership and Occupation of Land

Most wills contain details of land holdings. There is a description of the land and whether it was freehold, leasehold or copyhold and any conditions under which it was held, such as the lives of named individuals. Wills may therefore alert you to the existence of title deeds and if the land was held by copyhold, further useful information may be found in manorial records. There may even be an indication of how the land was inherited or from whom it was purchased. Cornelius Giles, in his will proved in 1850, states that he had purchased the Swan Inn in Wylye from his friend, William Thompson, in return for an annuity of £20 a year for his life, along with that of his brother, George Giles.

Signatures

Probate records can reveal whether your ancestor was literate, as testators, administrators and witnesses had to sign their name or make their mark. If they signed their name, this can be useful for identification, as you can compare the signature with that found on another record, such as a marriage entry. I found a beautiful signature for my ancestor, Philip Bennett, who acted as an administrator upon his father’s death in 1791:

Conclusion

The wills of Wylye are fascinating and give a valuable insight into the lives of the inhabitants of the village over the centuries. They provide wonderful genealogical information and even if you ancestor did not make a will or died intestate, you may well find them mentioned within probate records, whatever their social status. Searching by place, rather than by name, can yield unexpected treasures. In the future, I hope to look at surviving probate records for Wylye pre 1700 and expand my search to neighbouring villages. Likewise, additional wills and administrations held by the Prerogative Court of Canterbury can be found through searching by place*. I hope you feel encouraged to undertake a similar exercise and see what amazing information you can find on your own family within these amazing records.

© Judith Batchelor 2022

* If you search the records of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, I have found it better to use the website of the National Archives (U.K.), http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk as the search engine includes variants of place names.

Thank you for a comprehensive and informative post. It’s a great tip to search by location, and view other wills in the same location.

I’d also like to add that the FamilySearch wiki is very helpful to determine which court(s) had jurisdiction over your parish of interest, and where one might find a will, if it exists.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you enjoyed my post. I am a real fan of searching record sources by location where possible. You can miss a lot by just searching by name.

I purposefully didn’t go into too much detail about searching for wills because otherwise, my post would be too long. You are quite right though, the Family Search wiki is very helpful for this purpose.

LikeLike

Superb post as always Jude – wills are possibly my favourite historical source to work with and I thoroughly enjoyed reading this! Thank you 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Sophie! Wills and newspapers are neck and neck for first place as my favourite record sources.

LikeLike

I am a late convert to the joy of wills (and newspaper archives!). I think The Wiltshire Wills Project (which they then … sold, I assume, to Ancestry is an incredible resource! More counties should do similar (ignoring the shocking lack of resources in the heritage sector!).

LikeLiked by 1 person

It would be amazing if all pre-1858 probate records were digitised and available online. I am very happy to have Wiltshire ancestry.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Terrific post, not least because I am currently researching wills in Wiltshire! Full of information and insight.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks! The Wiltshire probate collection on Ancestry is superb. So many people appear in wills in various guises. The only small niggle is that every record is described as a will, which of course, is not the case.

LikeLike

What a thorough coverage of the value of Wills. Thank you for sharing this intriguing journey through the archives.

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed the post. 😀

LikeLike

A wonderful blog post full of details on wills and closely linked extras. Thanks so must for committing to writing useful posts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your encouragement!

LikeLike

Great post – as a result, I found that FamilySearch has unindexed wills/probate docs available via their website, though only viewable at an Affiliate Library or FHC…Fortunately the library I work at is an Affiliate 🙂 I know what I’ll be doing on my lunch break for the next few days…Thanks so much!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It takes a while to read through wills but you learn such a lot about both individuals and the local community. They are a great resource, enjoy!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I have ordered some later ones (post 1858) for various relatives, some direct, others collateral – but earlier ones may prove even more useful for all the reasons you outline 🙂

LikeLike

Hello.

There’s a lot to digest in Wonderful World of Will’s! I’ve skimmed through it one time and will read through it again. There is lots of useful information especially for a novice genealogist like me.

The reason I joined your site is because of your married name (Batchelor). My paternal and some maternal line is Batchelor. I’m from Onslow/Duplin County North Carolina but live in Alamance County North Carolina now.

My second cousin sent me a letter years ago stating that our Batchelor ancestor William was arrested in England for being a Quaker. She said he came to Virginia in 1648 with several friends. She said his son sailed from Bristol England in 1661 at the age of 16. His birth place was Buckingham Shire England.

If you run across any of this information could you notify me?

Jimmy H Batchelor

LikeLike

Hi Jimmy,

It was interesting to hear of your Batchelor Quaker roots in Buckinghamshire. My Batchelors were from Kent but Buckinghamshire is a county where Batchelors are found from the earliest dates. Quakers and their persecution are well-documented so you may be able to find out some more information about your ancestor, William Batchelor. You might find this article on the website of Amersham Museum helpful:

https://amershammuseum.org/history/research/religion/quakers-in-the-chilterns/

If you contact the Museum, they may be able to put you in touch with someone who could help further.

Best wishes,

Judith

LikeLike

I really enjoyed this, Jude. Not only do you provide great examples of the many ways wills can help a family historian, but you have uncovered so many personal moments, such as snide remarks and touching bequests.

Last year I found that there are 33 PCC wills for Whaddon, Bucks (one of my ancestral villages) available via TNA. I already have many wills for my Whaddon ancestors (from the Archdeaconry of Bucks) but I really ought to download the PCC wills while downloads are still free, and perhaps view more Whaddon wills at Bucks Archives, as you’ve reminded me how rich a resource this could be.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Clare, there is so much to love about wills and the PCC wills are now so accessible. Richard Holt told me about the Bucks Will Index, which indexes all names in the probate documents:

https://www.bucksfhs.org.uk/index.php/database-searches/family-history-news/25-other-bucks-news/384-bucks-wills-index-on-line

It sounds marvellous!

LikeLike

Buckinghamshire Archives also has an online of Buckinghamshire Wills, but it is fairly hidden. This does not give names of other individuals mentioned in wills and only includes some administrations. It does, however, provide the references to both the original will and the registered copy (depending on in both survive). The link to the index is here: https://shop.buckscc.gov.uk/s4s/WhereILive/Council?pageId=2347&pid=36803787-1a6a-4c46-bbfb-a5ad00f89b6b&supId=c988f85e-be98-4bf3-b184-a5ad00efd350&bcgId=fcea1611-2a26-4a1d-a4a6-b480f7423e14 Once you have the references, if you are at a FamilySearch Family History Centre or Affiliate Library you can look up the document here: https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/7350?availability=Family%20History%20Library

LikeLike